[Mother’s Day Feature] The Growing Motherhood Movement: When Parents Get Political

Posted May 7, 2010 1:41 pm.

This article is more than 5 years old.

For many people becoming a parent alters their perception of the world and prompts a sense of duty to change things for the better and the groundswell of motherhood movements across North America over the past decade may be a testament to that.

“I think the motherhood movement is kind of like the new women’s movement that happened in the [1960s] and 70s and now … there’s a real sense of momentum,” Andrea O’Reilly, a professor of women’s studies at York University and the founder of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement (MIRCI), told CityNews.ca.

The genesis of the movement here in Canada may have started back in the 1990s when a grassroots coalition of women, led by the group Mothers are Women, fought to have unpaid domestic work included on the national census in order to legitimize the efforts of mothers and caregivers.

Three questions about unpaid work were included in the 1996 census.

Linn Baran, who heads up the MIRCI-affiliated group Mother Outlaws, said when she had her son in 2001 she noticed a marked tone change in the discussion about mothering.

“There was that notion that, yes, motherhood is wonderful, but it’s not all hearts and flowers. It is hard work, but it’s not acknowledged and it doesn’t need to be that way,” she said.

“If it’s harder than it needs to be, then maybe we should be asking for some change.”

Highly organized mother-led activism is especially strong in the United States right now and includes groups like Moms Rising, which fights for parental and maternity leave, universal access to quality child care and pay equity; Mothers Acting Up, a group that takes action for improved environmental standards, tougher action on child poverty and increased child security both in the U.S. and abroad; the Big Push for Midwives, which is fighting for improved maternal health care through licensed midwifery and the group that organized the Million Mom March, which campaigns for stricter gun control laws.

Journalist Jennifer Block’s 2007 book “Pushed: The Painful Truth About Childbirth and Modern Maternity Care” helped fuel the fight to improve the situation for expectant moms in the U.S. The Ricki Lake-Abby Epstein documentary “The Business of Being Born” was released a year later and helped galvanize the effort even further, especially in New York, where there is a strong homebirth movement.

“This all kind of started to really catch fire I’d say in the last five years,” Block said.

Many American women are fighting for the right to give birth in their homes and in hospital with the help of midwives in response to a medical environment Block believes depends too heavily on intervention and doesn’t respect the importance of normal, physiological birth.

“It’s part of our culture that we don’t value this process,” she said.

The rate of caesarean section in the U.S. is just over 30 per cent and some speculate the fear of potential lawsuits prompts doctors to push for surgical intervention more often than is necessary.

“Unfortunately, in spite of decades of evidence, we don’t see typical standard maternity care as being evidence-based.”

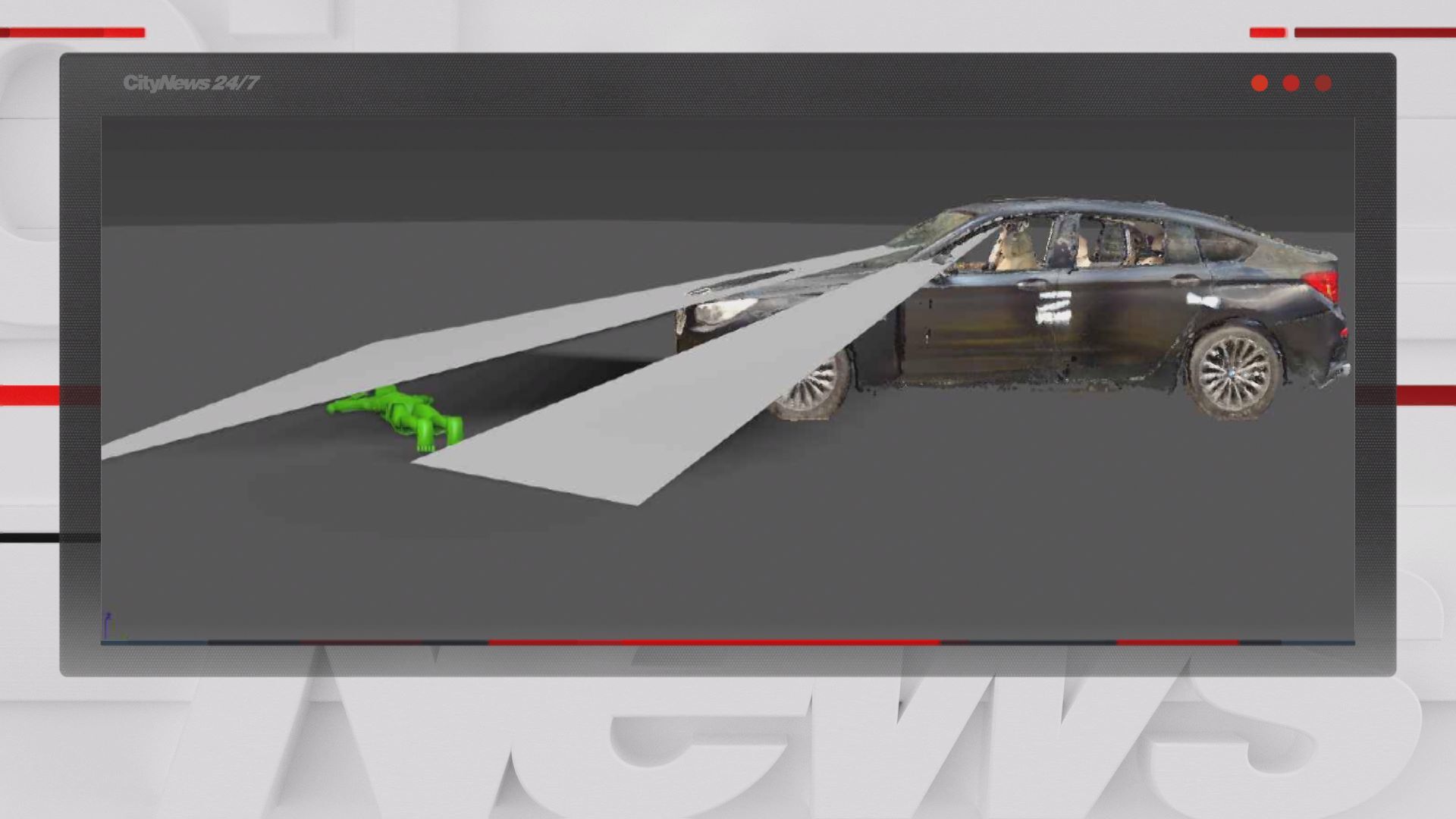

Still from “The Business of Being Born”

Here in Canada, midwives are licenced across most of country, but parents on both sides of the border face similar hurdles when it comes to child care.

Baran believes mothers are being shortchanged by the federal government’s monthly $100 per child Universal Child Care payment. She thinks a national child care program would make lives easier for families.

“People are being pushed out [of the workforce] when you don’t really have choices in terms of quality of life or adequate income and benefits under part-time pay to make things work best for all,” she said.

Diane Watts of Real Women of Canada, a 27-year-old group that describes itself as the country’s alternative women’s movement, doesn’t support that idea.

“We don’t want to sort of corral women and men and children into the government-funded and controlled universal daycare system,” she said.

“We’re in favour of the wide system, starting with a realistic choice to care for your own child if you want for as long as you want without suffering undue penalty or punishment because you’re not going along with the accepted ideology of the time, which happens to be tax-funded feminism.”

Sharon Lerner’s recently published book “The War on Moms: On Life in a Family-Unfriendly Nation” examines the difficulties parents face in the United States with regard to work and childcare options, among other issues.

“What I wanted to do, partly, is make people feel a little less guilty about having a difficult time. I think a lot of American parents feel terrible that they can’t do a great job, as good a job as they’d like as both mothers and workers,” Lerner explained.

“What I want to say is hey, you can’t do this because it’s actually not possible and the only way really to make it possible is to change things.”

The journalist said one major hurdle is the fact women in the U.S. often have to return to work weeks and sometimes days after giving birth because there is no paid parental leave.

“That is brutal for the mother and often for the child,” she said.

Parents on both sides of the border have campaigned hard for tougher environmental standards and activists and bloggers helped raise awareness and organize campaigns against toxic chemicals in children’s toys and other items, including baby bottles.

Improving children’s well-being throughout every stage of their lives drives many parents to take action, but the death of a child has also prompted powerful mother-led movements.

Mothers Against Drunk Driving was formed in 1980 by California mother Candace Lightner after her 13-year-old daughter Cari was killed by a drunk driver.

“You think what they did in a very short period of time. They made drunk driving unacceptable,” O’Reilly explained. “That’s a huge cultural shift in 30 years.”

And a profound loss moved Audette Shephard to action. She formed United Mothers Opposing Violence Everywhere (UMOVE) after her 19-year-old son Justin, her only child, was shot to death on a footbridge near Bloor and Sherbourne on June 23, 2001. His murder hasn’t been solved.

“My call to action came when my son was murdered and my message to mothers and the community as a whole is not to wait until tragedy happens,” she said. “We need to move together as a community … at the end of the day, we’re all accountable.”

“Out of much sorrow came much resolve and I put this in my heart to do whatever I can to make a difference so that another mother doesn’t have to go through this. It’s not easy.”

In 2004, the city of Toronto proclaimed Oct. 21 as the UMOVE Day of Non-Violence.

Shephard has worked closely with Mayor David Miller on anti-violence initiatives and she has spoken out against the Conservatives’ efforts to scrap the federal gun registry.

Shephard also sits on the board with the Attorney General for the provincial Office for Victims of Crime, fighting for increased support services.

“You don’t plan, you don’t put aside money for your son’s funeral, so these are the types of things that are important, the counseling pieces, the financial help,” she said.

The anti-violence activist said the fact that she’s a mother may add even more weight to her message.

“There are times when I talk to young men and I say think of your own mother in this situation, and you can see the change, you can see the shift.”