Election day in Quebec, with polls pointing to change in government

Posted September 4, 2012 6:06 am.

This article is more than 5 years old.

An era of tranquility on the national unity front could end Tuesday as polls suggest the pro-independence Parti Quebecois is favoured to return to office after nine years in opposition.

The sovereigntist party has led in surveys throughout the campaign with its support pegged in the low-30s, leaving open the question of whether a majority government is within reach.

The polls close Tuesday evening at 8 p.m. ET.

A Parti Quebecois victory would terminate the reign of Jean Charest, the resolutely pro-Canada premier who made the transition from national politics in 1998 when the federalist forces in the province were leaderless and fearful of another sovereignty referendum.

Charest’s Liberals have won the popular vote in every provincial campaign he has led and, since 2003, they have held power with three straight election victories.

The intervening years have seen his government occasionally clash with Ottawa over policies related to criminal justice, the environment and health transfers but those skirmishes have generally been brief and sporadic.

The party that polls and many observers expect to win tonight is the one that was consistently pushing Charest to take a harder line against Ottawa, and that frequently accused him of sacrificing Quebec’s interests for fear of creating a schism with Canada.

The PQ would have no such qualms about schisms. The idea of confrontation with Ottawa is a central theme built into its platform.

The party plans to either demand or create new provincial powers, including a “Quebec citizenship.” To get that document, future immigrants would have to prove they speak French, and the document would be a requirement to run for public office.

The party would also demand a transfer of powers from Ottawa that touch on domestic and international affairs. Targets include Employment Insurance, copyright policy and foreign-assistance funding.

Should the Supreme Court get in the way of any new language laws, or should Ottawa say no to any request, the PQ has a backup plan: use each defeat as kindling to stoke the embers of the independence movement.

“There are a multitude of examples where we can make the demonstration that we would be best served if we decided for ourselves,” Marois said during the campaign.

“It’s obvious that (each federal rejection) will demonstrate the impossibility that we will ever be recognized as a distinct society.”

Support for independence has always been highest when Quebec was involved in a dispute with the federal government, or with governments in other provinces. Two examples are the early 1990s, when an attempt to get Quebec constitutionally recognized as a “distinct society” failed, and the height of the sponsorship scandal in 2004.

But the PQ has its work cut out for it, if it hopes to revive the flames of independence.

A recent survey pegged support for sovereignty at 28 per cent — or roughly half the historic levels recorded in the early ’90s.

Marois has sought to reassure moderate voters that there will be no automatic referendum under her watch.

“I am a responsible woman,” said Marois, an experienced politician who held no less than 15 cabinet portfolios under Rene Levesque, Jacques Parizeau, Lucien Bouchard and Bernard Landry.

“I have convictions and I am going to defend them. There will be a referendum when the Quebec population wants a referendum.”

There has been one major wildcard throughout this election: Francois Legault’s new Coalition party.

With the polls relatively tight, it has never been clear whether this new party might ultimately play the role Tuesday of contender, spoiler, king-maker, or non-entity.

Less than a year old, the party gobbled up the ADQ and touted itself as a third way for voters seeking to turn the page on the province’s highly polarized politics.

Its leader is a former PQ cabinet minister and, until recently, an ardent sovereigntist. Legault’s caucus and his entourage are a mix — hence the name “Coalition” — of sovereigntists, staunch federalists, and middle-of-the-road-nationalists.

The party proposes pausing the independence debate for at least a decade. In the meantime, it wants to make structural changes in health care, education and economic policy.

The Coalition’s proposed changes include shifting high schools to a 9-to-5 schedule, abolishing school boards, and providing a family doctor to every resident.

Its economic policies include several nods to the right, such as a call for cuts in the public service, and some to the left such as a proposal for larger state support for Quebec companies.

It has also recruited the most famous anti-corruption whistleblower in the province and promises to clean up graft and collusion in the public-tendering process.

The Coalition has made gains in polls over the course of the campaign but none has pointed to a victory for the new party.

Apart from the possibility that the polls are off, there are still several factors that could leave the election result up for grabs: a late shift in support, the strength of get-out-the-vote operations, or bizarre local splits in the three-way race.

The PQ will be wary of having its votes siphoned off by Quebec solidaire and Option nationale, which are also left-leaning sovereigntist parties. Conversely, the Liberals and Coalition could split the anti-sovereigntist and right-leaning vote.

Charest was an underdog when he called the election. But he entered into it at a moment many considered the most hospitable timing for his party.

The province’s corruption inquiry is off during its summer holiday — and the return to school is on.

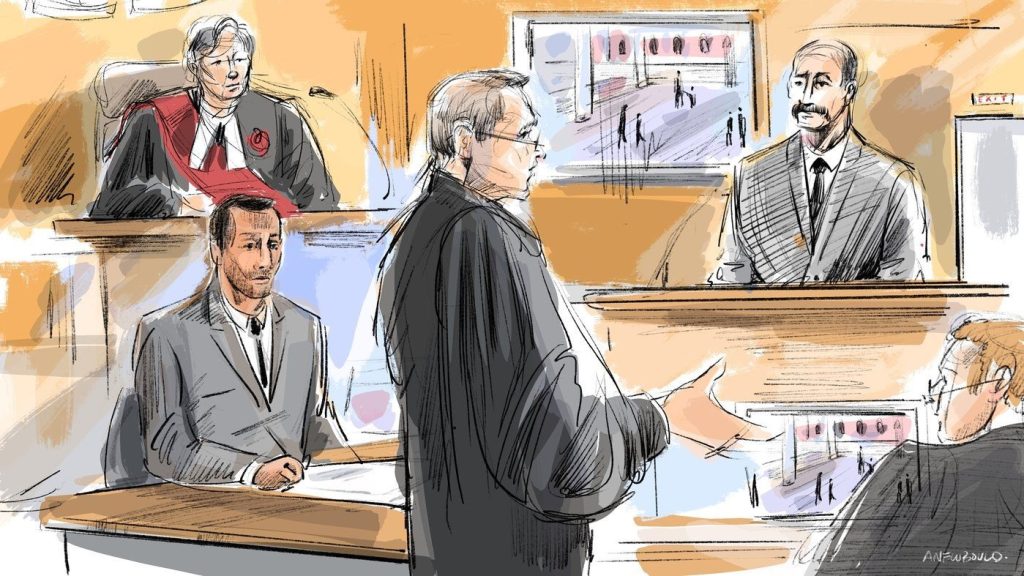

That timing might have helped push to the background ethics scandals that dogged his government such as the minister, Tony Tomassi, who quit politics and is set to appear in court on fraud charges.

Charest wanted to talk about law and order of another kind — in other words, not yielding to student protesters.

Just over a month ago, Charest kicked off the election campaign with an appeal to what he called “the silent majority,” meaning those voters who opposed last spring’s protests and who might be eager to punish the PQ for supporting them.

But the protests died down during the campaign. Most students have gone back to class, and only a few holdout university faculties and the most ardent protesters have kept up the fight.

So the battle over tuition never wound up taking centre stage.

A protest with people banging pots and pans, of the sort often seen since the spring, was larger and more festive than usual in Montreal Monday night as demonstrators celebrated the anticipated demise of the Liberal government.

Charest also tried to frame the election as a choice between job growth and prosperity and the upheaval of a sovereigntist PQ government.

He argued the Coalition would also lead to instability in fragile economic times.

Charest joked that if the PQ won, and called a referendum, Legault would have to spend the campaign hiding in his basement. Legault’s party has no official policy on whether Quebec and Canada should, in the long term, be one country.

While trying to woo federalist voters recently, Legault said he would vote against independence in a referendum even if he didn’t participate in the campaign. He also recently described himself as a “Canadian.”

But he says he wouldn’t campaign for Canadian unity.