How sexual assault survivors fight the courts to get justice

Posted March 9, 2021 4:32 pm.

Last Updated December 7, 2021 2:07 pm.

Jane has had plenty of nightmares about the worst night of her life. She gets sexually assaulted, and in those moments, she cannot scream, and she cannot move, paralyzed by fear. “I just want to die because I don’t want to feel that in any way,” she said.

It’s a nightmare Jane said she first woke up from on a Sunday morning in December of 2017. Only then, she had lived it.

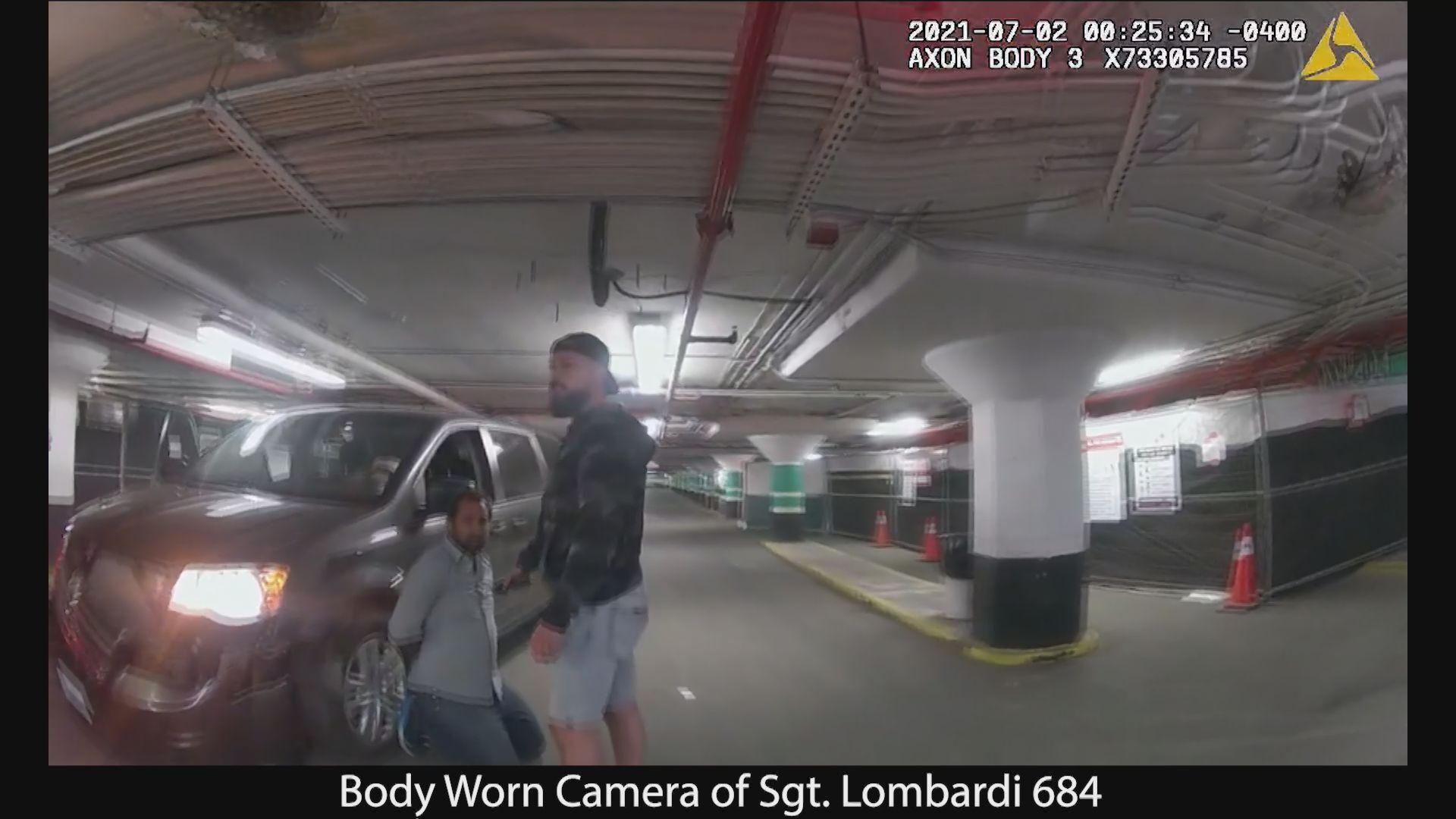

Jane is not her real name, but because of a court-ordered publication ban CityNews cannot identify her. After her sexual assault, Jane confronted her friend about the night he drove her home, unbuttoned her shirt while she was asleep in the passenger seat, and molested her.

Over the next two weeks Jane and her assaulter exchange several texts, in which he apologizes. “The perpetrator said, ‘I’m sorry I sexually assaulted you, molested you, touched your body without your consent,’” she told CityNews.

Jane reported her abuse and handed over the texts to police, and an arrest was made two weeks later. But it’s when she began navigating Canada’s court system a year-and-a-half after the assault, that Jane said she once again found herself without any control.

“That’s kind of where my troubles begin, I think.”

‘I’m simply a witness. And that’s how they treat you’

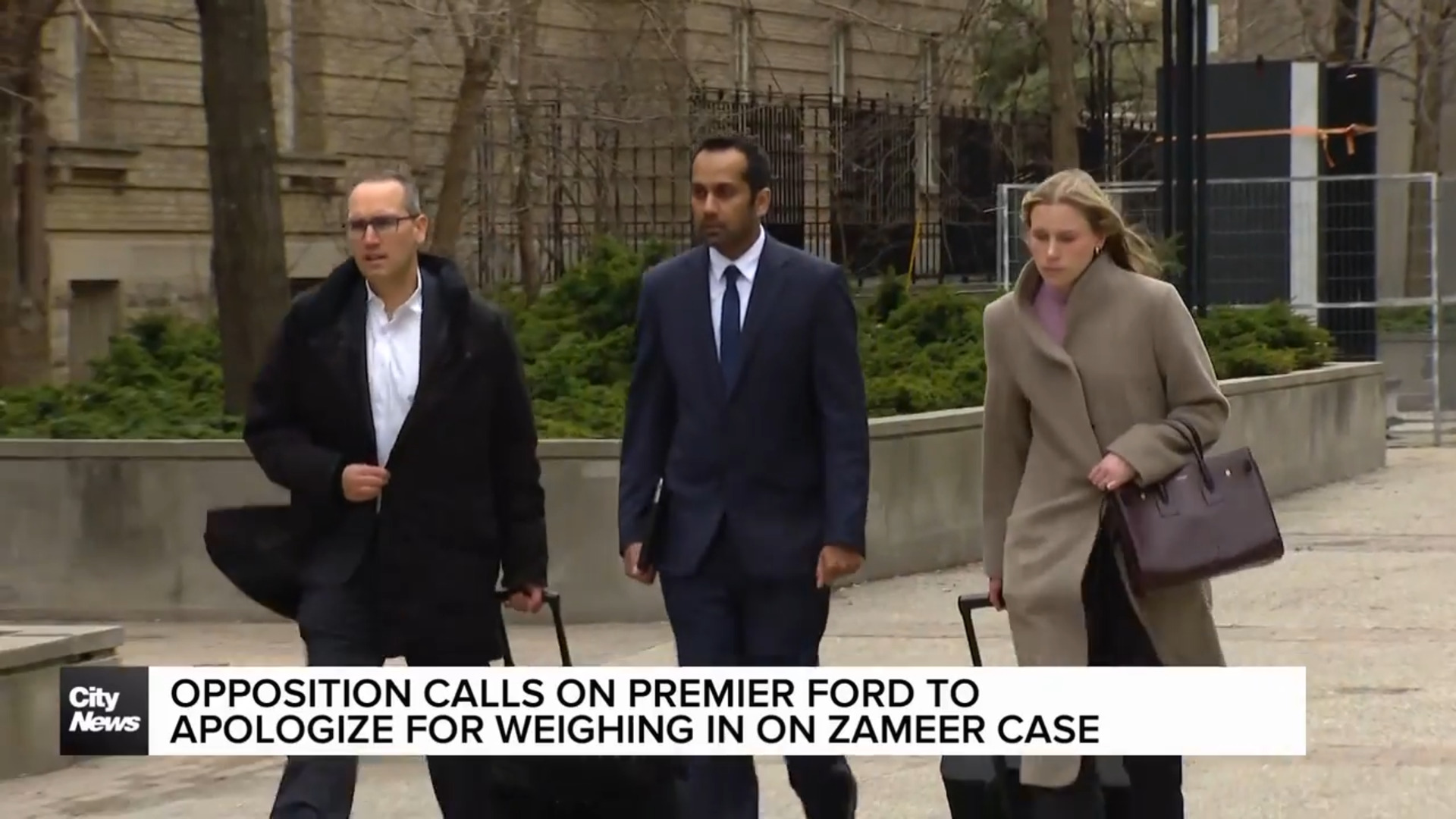

When Jane decided she did want to go through with a trial, she was shocked to find out she would have no legal rights or representation. Rather, she would be a witness in the state’s case against her assaulter.

“That is one of the biggest reasons why survivors going through the criminal justice system in cases of sexual assault find it extremely difficult to navigate,” said Deepa Mattoo, executive director at the Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic, a specialized legal clinic in Toronto for women experiencing violence. “[Survivors] have very little to do with the process and it is other people making decisions.”

The day before the trial, Jane met with the Crown prosecutor for the first time. The meeting lasted about an hour. “Nobody really told me anything, I was just kind of told to show up,” Jane said.

“When the perpetrator is allowed to hire the best attorney in town, and prepare for months in advance, and the victim gets one hour with the Crown attorney one day before the trial, the scale is already tipping in favor of the perpetrator.”

“Many Crown attorneys do not have adequate time for this preparatory work with victims in the currently backlogged, and often significantly under-resourced, court system,” reads a 2019 report for Justice Canada. “This presents a systemic challenge, and requires a remedy if the criminal justice system is seriously going to move towards becoming trauma-informed and more supportive of sexual assault victims,” the report says.

But Mattoo added there is no real accountability of the legal system itself and that change has to come from within. “This design continues to create this environment where there is no accountability for, what was your role and how trauma-informed were you?” she said. “No one is asking these questions.”

Mattoo said Crown prosecutors, criminal lawyers and sitting judges should be required to take sexual assault education. But she noted any mandatory legal training on sexual assault must be comprehensive and happen with consistency, rather than take a checklist approach.

‘If I had been robbed…I think he would have gotten a more serious sentence’

According to Statistics Canada, Jane is just one in 10 Canadians whose sexual assault ended in a conviction. Jane was even more disheartened after her assaulter was handed down one-year of probation with few conditions attached.

While Jane said she wasn’t expecting her assaulter to be imprisoned, she did want the system to hold him accountable in a way that promoted a sense of responsibility and acknowledged the harm done. “If I had been robbed,” she said, “I think he would have gotten a more serious sentence.”

Mattoo cautions about the unintended consequences of what some may consider a serious sentence on racialized communities. One suggestion she has is involving other professionals – such as social workers, community safety officers or health service providers – in the rehabilitation process and developing a more coordinated response to the management of the offender’s behaviour.

“I wouldn’t necessarily say that the survivors are looking for harsher sentences. They’re looking for appropriate sentences,” said Mattoo.

Finding justice elsewhere

After a retraumatizing court process that left Jane feeling disappointed, she pursued litigation in civil courts – where she said she got to call the shots and have her trauma acknowledged.

She’s wants to give this message to other victims: know what options are available. A key element of that is getting independent legal advice, Jane said – something she wishes she had done.

Complainants in sexual assault cases currently have to pay for their own lawyers. But the Barbra Schlifer Clinic is one of the sites in a pilot project launched by the Ontario government that gives victims in Toronto, Ottawa and Thunder Bay access to four hours of free legal advice. Jane would like to see the pilot made permanent and available provincewide.

She believes empowering victims can be as simple as ensuring they’re well informed, which she said will go a long way in bridging the justice gap. While Jane said she doesn’t have closure, she’s moving forward, motivated to help those who come after her get justice for themselves.

“I want to make a difference for other people.”