Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter dead at 76

Posted April 20, 2014 10:30 am.

This article is more than 5 years old.

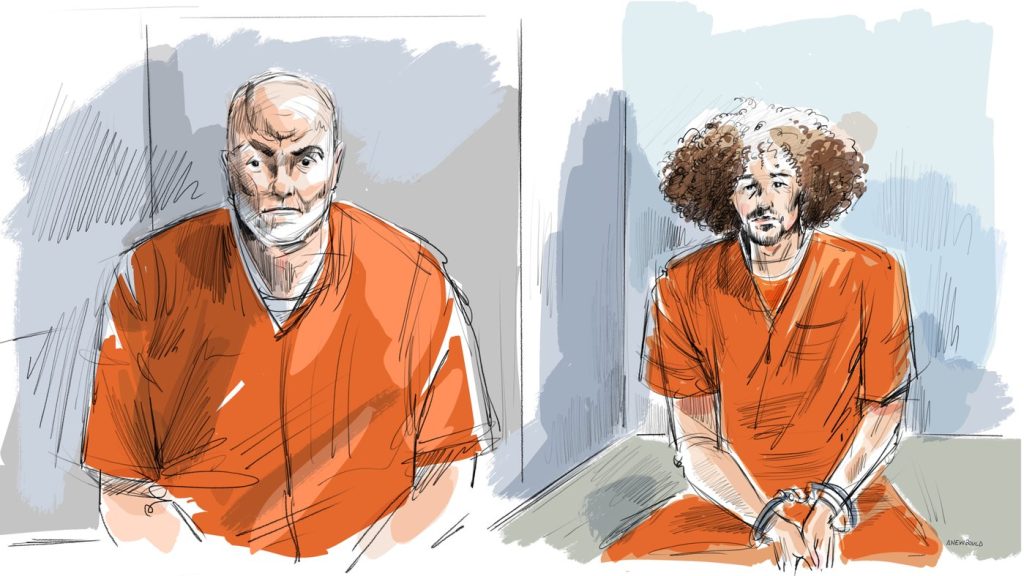

Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the former American boxer who became a global champion for the wrongfully convicted after spending almost 20 years in prison for a triple murder he didn’t commit, died at his home in Toronto on Sunday.

He was 76.

His long-time friend and co-accused, John Artis, said Carter died in his sleep after a lengthy battle with prostate cancer.

“Rubin was a fighter in every aspect of the word,” Artis explained to CityNews. “Even with his disease and his dying, he was fighting against that.”

Artis said he quit his job stateside and moved to Toronto two years ago to act as Carter’s caregiver after his friend was diagnosed with cancer.

“”It was basically a no brainer. It was basically – I’m on my way partner,” he said. “The epitomization of loyalty to a friend.”

During the final few months, as Carter’s health took a turn for the worse, Artis said the man who was immortalized in a Bob Dylan song and a Hollywood film came to grips with the fact that he was dying.

“We used to have conversations and he would say I’ve done everything I wanted to do, I’ve achieved everything I want to achieve, I’ve seen everything I want to see, there’s nothing else on this earth that I have to do,” Artis said.

“He tried to accomplish as much as he possibly could prior to his passing,” Artis told The Canadian Press, noting Carter’s efforts earlier this year to bring about the release of a New York City man incarcerated since 1985 — the year Carter was freed.

“He didn’t express very much about his legacy. That’ll be established for itself through the results of his work. That’s primarily what he was concerned about — his work,” Artis said.

Born on May 6, 1937, into a family of seven children, Carter struggled with a hereditary speech impediment and was sent to a juvenile reform centre at 12 after an assault. He escaped and joined the Army in 1954, experiencing racial segregation and learning to box while in West Germany.

Carter then committed a series of muggings after returning home, spending four years in various state prisons.

He began his pro boxing career in 1961. He was fairly short for a middleweight, but his aggression and high punch volume made him effective.

Carter’s life changed forever one summer night in 1966, when two white men and a white woman were gunned down in a New Jersey Bar.

Police were searching for what witnesses described as two black men in a white car, and pulled over Carter and Artis a half-hour after the shootings.

Though there was no physical evidence linking them to the crime and eyewitnesses at the time of the slayings couldn’t identify them as the killers, Carter was convicted along with Artis. Their convictions were overturned in 1975, but both were found guilty a second time in a retrial a year later.

After 19 years behind bars, Carter was finally freed in 1985 when a federal judge overturned the second set of convictions, citing a racially biased prosecution. Artis was also exonerated after being earlier paroled in 1981.

Carter later moved to Toronto and became the founding executive director of the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted, which has secured the release of 18 people since 1993.

Win Wahrer, a director with the association, remembers Carter as the “voice and the face” of the group.

“I think it’s because of him that we got the credibility that we did get, largely due to him — he was already a celebrity, people knew who he was,” she said.

“He suffered along with those who were suffering.”

Though Carter left the organization in 2005, the phone never stopped ringing with requests for him, Wahrer said.

“He was an eloquent speaker, a passionate speaker. I remember the first time I ever heard him I knew I was in the presence of a man that could move mountains just by his presence and his words and his passion for what he believed in,” she said.

Carter went on to found another advocacy group, Innocence International.

“He wanted to bring people together. That was his real purpose in life — to get people to understand one another and to work together to make changes,” said Wahrer.

“It was so important for him to make a difference. And I think he did. I think he accomplished what he set out to do.”

Association lawyer James Lockyer, who has known Carter since they were involved in the wrongful conviction case of Guy Paul Morin, remembered how Carter called him just before sitting down with then-president Bill Clinton for a screening of his 1999 biopic “The Hurricane.”

The call was to ask for advice on how to bring the U.S. leader’s attention to the case of a Canadian woman facing execution in Vietnam.

“Even though this was sort of a pinnacle moment of Rubin’s life — to sit at the White House with the president and his wife on either side of him watching a film about him — he wasn’t really thinking about himself,” said Lockyer.

“He was thinking about this poor woman who was sitting on death row in Vietnam that we were trying to save from the firing squad.”

The film about Carter’s life starred Denzel Washington, who received an Academy Award nomination for playing the boxer turned prisoner.

On Sunday, when told of Carter’s death, Washington said in a statement: “God bless Rubin Carter and his tireless fight to ensure justice for all.”

Carter’s fight continued to the very end.

Never letting up even as his body was wracked with cancer, Carter penned an impassioned letter to a New York paper in February calling for the conviction of a man jailed in 1985 to be reviewed — and reflected on his own mortality in the process.

“If I find a heaven after this life, I’ll be quite surprised. In my own years on this planet, though, I lived in hell for the first 49 years, and have been in heaven for the past 28 years,” he wrote.

“To live in a world where truth matters and justice, however late, really happens, that world would be heaven enough for us all.”

With files from Toronto Staff