25 years after Ipperwash Crisis, the fight for land continues

Posted September 7, 2020 12:45 pm.

Last Updated September 9, 2020 6:03 pm.

“You have to take a stand, even if it costs you, you’ve still got to take a stand,” Pierre George says on the 25th anniversary of his brother Anthony ‘Dudley’ George’s death.

“Dudley is a prime example of that. All he was trying to do was turn away from the bullets and he got shot.”

On September 6, 1995, Dudley was part of a group of unarmed Indigenous protesters stationed in the former Ipperwash Provincial Park in an effort to reclaim nearby reserve land.

His family was one of several who were forced from Stony Point (known as Aazhoodena), a nine square kilometre tract of land near the shores of Lake Huron under the 1942 War Measures Act. The provincial park lies adjacent to that land and houses an ancestral burial ground.

Under political pressure, the OPP descended on the park that Labour Day to remove the unarmed protesters.

“The way they came here, with what they had, I’ve never seen the OPP do that to anyone,” says Tom Bressette, the longstanding former Chief of the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point.

“They come in with armoured personnel carriers, all of the officers had gas masks and the latest weapons they all borrowed [from the military]. All brand new goods to make sure they did the job they were to do.”

That job was to remove the protesters – and they succeeded. But only after officers beat a council member to near death, shot a 15-year-old boy and killed 38-year-old Dudley George.

The sniper who killed George, Acting OPP Sgt. Ken Deane, was later convicted of criminal negligence causing death.

“It’s difficult, all the memories come back,” Pierre says reflecting on the night.

“What I had to go through to save my brother, he died on the way to the hospital and that’s all there is to it.”

Pierre and his sister Carolyn raced across back roads to get their brother to a hospital in Strathroy, Ontario. Dudley was declared deceased on arrival.

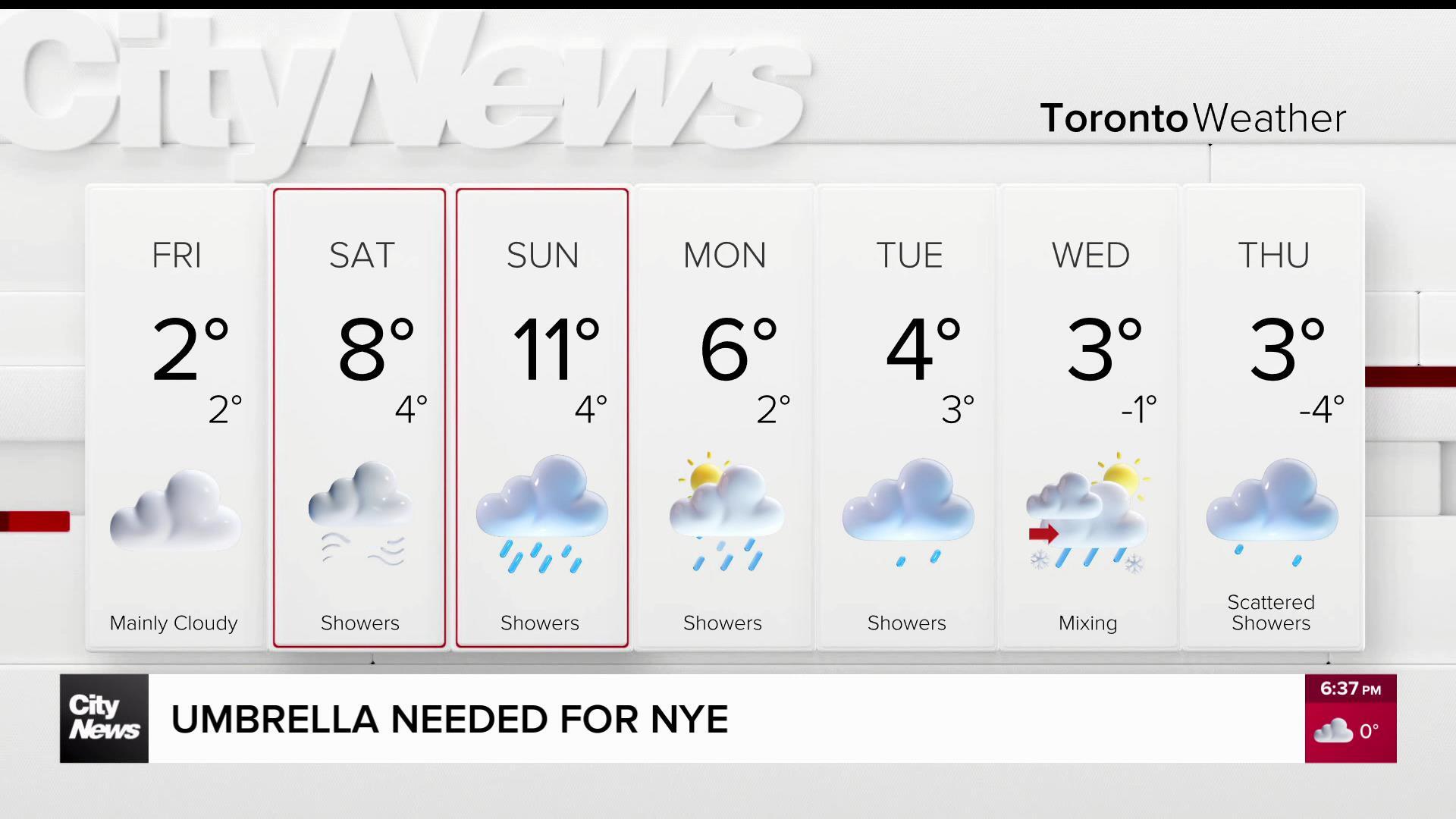

Pierre George, brother of Dudley George, who was killed by an OPP sniper in the former Ipperwash Provincial Park on September 6, 1995. CITYNEWS/Cristina Howorun

The lack of medical teams on standby was one of several failures of the OPP and provincial and federal governments, according to the Ipperwash Inquiry. The inquiry was a delayed examination of what would later become known as “The Ipperwash Crisis.”

George’s death, and the ensuing inquiry, helped pave the way for the return of the land to the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point.

“There were a few small postage stamps [of land] that we did not want to give up. Stony Point was one of those postage stamps. It was so valuable, so sacred to us that we did not want to give that up,” Kettle and Stony Point Chief Jason Henry says.

In 1942, the Canadian government offered residents of Stony Point, which is located about 40 kilometres from Sarnia, $15 an acre (4046 square metres) for their land so the military could use it as a training camp. When the community refused, the government used the War Measures Act to seize the land and forced residents to relocate to Kettle Point, about 10 kilometres away.

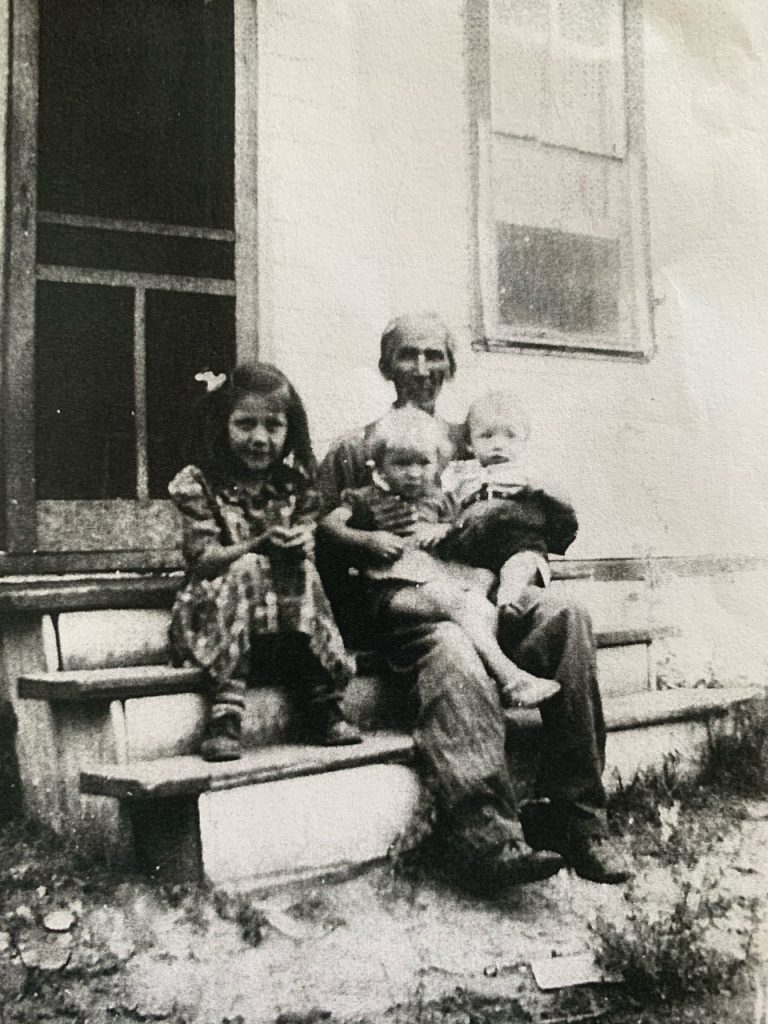

“Apparently under the War Measures Act you can do that. So they did it, but they did promise us that they were going to give it back, when they no longer needed it,” says Carol Pelletier, the last person born on the land. Her grandparents were medicine gatherers and were forced away from their traditional grounds.

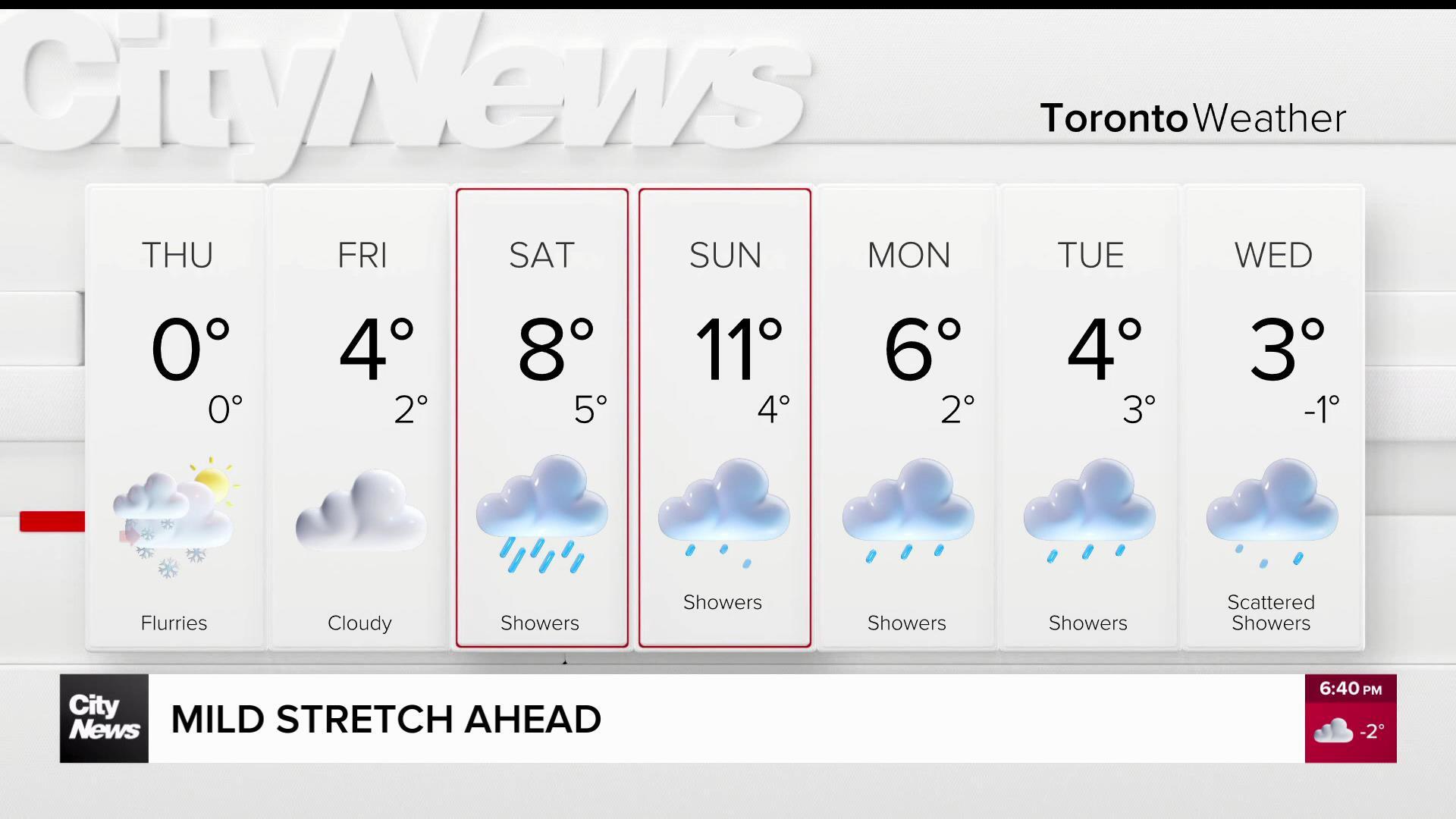

Carol Pelletier says she grew up feeling like a refugee after the government forced her family to leave Stony Point. CITYNEWS/Cristina Howorun.

“It was traumatic because they spent their life there. They were just told to get out of there. The army moved in. They didn’t wait for us to move out. The army moved in,” says Pelletier.

“All the land we had was taken from us and stripped away from us,” Bressette says. “We had fish. We had all kinds of things to make us live without anybody’s help. And they took that away.”

Some homes were bulldozed by the army, while others were hoisted on trucks and moved to Kettle Point. Pelletier says she grew up feeling like a refugee in her own country.

“It was much harder. There were people who had their set land already.”

Pelletier says the government gave Stony Point residents no choice as to where their new homes would be. “We just had to be placed wherever they wanted to place us. So a lot of the time, it was a small parcel or not very desirable land.”

Carol Pelletier and her family after their forced relocation to Kettle Point.

Dudley George’s family was one of those forced to relocate. “My dad was born at Stony Point, I know exactly where his house was,” says Pierre George.

The promise was the land would be returned when WWII was over, but the military didn’t want to hand it back.

In the 1970s, then Minister of Indigenous Affairs Jean Chrétien lobbied his own government to return the base. But it continued to be used as a summer training camp.

There was little movement until the early 1990s when a small group of descendants peacefully moved onto the outlying areas of the army camp in an effort to reclaim their land. Slowly they gained ground and eventually, by some level of force, reclaimed the army camp.

A Final Settlement Agreement was reached between the First Nation and the government in 2016. It offered compensation for the land and promises to officially return it once the military cleared the land of contaminants and potentially thousands of unexploded ordinances.

“What happened down there, when they blockaded down there […] if that hadn’t happened I doubt this would have been dealt with yet,” Bressette says reflecting on that dark night twenty five years ago.

Today, about 60 people live on the former camp, including Lacey George. She’s lived there for 13 years with her partner, Kevin, one of the original community members in the reclamation efforts.

“I wouldn’t be able to live in the home I’m in,” Lacey George says of Dudley George’s sacrifice. “Its sad to know that for us, it’s this big historical event that empowered everybody here.”

“It sucks to know that as much as you might look at that person as your hero, not everybody may see him that way. I wouldn’t have the home that I have, the husband that I have, my kids wouldn’t have the life that they have, if I didn’t up and move down here,” she says outside her home, which is a former army barrack.

“The people who are at Stony Point are land defenders. They, on behalf of our community and our ancestors, jumped the fence in 1993,” Henry says.

“They’ve defended the land ever since. And they were charged by their grandparents and parents to protect the land at all costs, until we can effectively move home.”

A man pays his respects at the site where Dudley George was killed by police. CITYNEWS/Cristina Howorun

It is a move that could take 20 to 25 years. Under an agreement with the Department of National Defence, land will only be handed over to the First Nation once it is cleared of environmental contaminants and unexploded ordinances – remnants of the military occupation of Aazhoodena.

Pierre George says he will continue to live in the former camp – despite the lack of running water in his home, limited electricity and potentially deadly unexploded ordinances, because it is home.

“That’s why I’m still here. It’s my home. Because I’ve put up with this much stuff already, why walk away now?”

More photos from Ipperwash area in the gallery below