First Nations communities see drop in COVID-19 cases following successful vaccine rollout

Posted May 4, 2021 5:00 am.

Last Updated May 4, 2021 8:47 am.

While Canada often looks to places like the U.K. and Israel to monitor the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, experts say data here at home also offers similar insight.

Between Jan. 10 and 16, there were 4,866 active COVID-19 cases reported in First Nations communities. Nearly four months later, that number has dropped to 739 cases between April 25 and May 1.

The drop in cases is being attributed to what experts are calling a successful vaccine rollout.

“It’s the same kind of drop you’ve seen in deaths at long-term care homes, where the majority of people early on in the pandemic were elderly people in long-term care,” Dr. Anna Banerji, infectious diseases specialist at Temerty Faculty of Medicine and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, explained.

“Once they were vaccinated, you see the rates of hospitalizations and deaths plummet. So the vaccines have worked in the Indigenous communities.”

Since mid-January, health professionals have administered over 233,232 vaccine doses in First Nations, Metis and Inuit communities.

Dr. Lisa Richardson is just one of the many healthcare professionals who has travelled north to administer hundreds of vaccines, where over 90 per cent of adults who were eligible received the shot. She boarded a flight from Toronto to Sioux lookout, and from there, she and her team took a one-hour plane ride to and from remote communities, over a four-day period.

“What we know from the numbers is that we have very few new active cases on reserves across Canada, because of how effective the vaccine rollout has been,” Dr. Lisa Richardson, strategic lead in Indigenous health, at Women’s College Hospital, said.

“We need to actually acknowledge and uplift the good story of what’s happened among First Nations in Canada, because we’re so used to hearing the negative.”

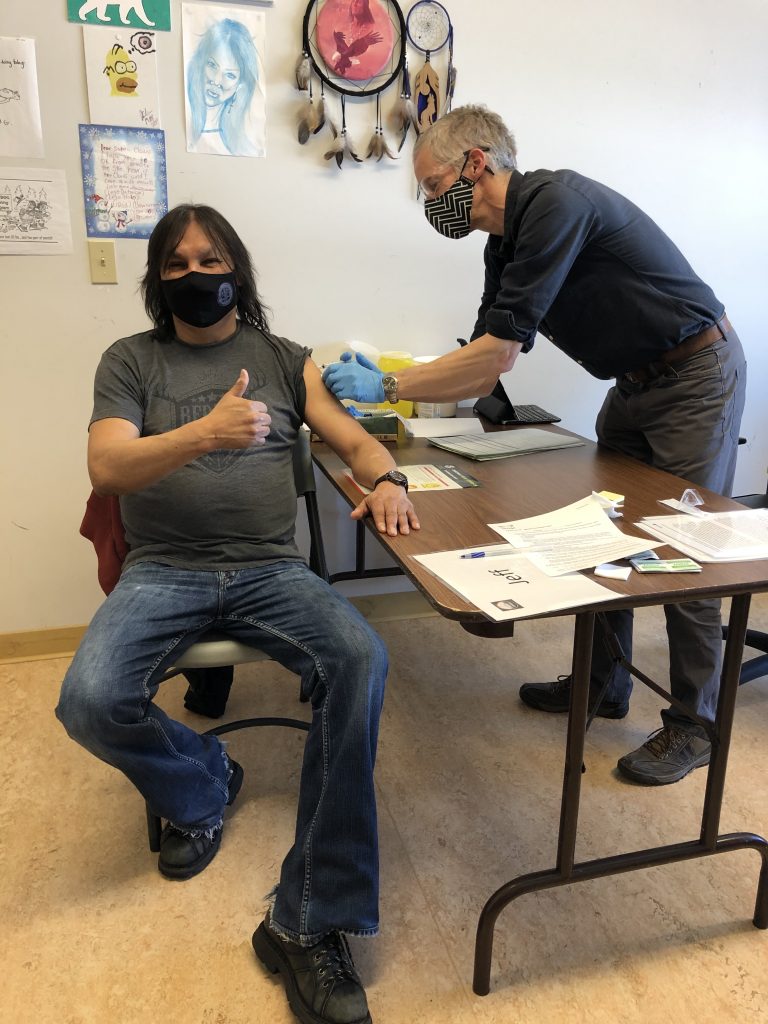

First Nations members get a COVID-19 vaccine

Public health measures continue to be in place throughout Canada. Banerji, who is also a pediatrician, noted that travel restrictions were also in place in certain northern communities.

“Diabetic nurses, dentists or other mental health workers, couldn’t go into the community so a lot of people didn’t get their health needs taken care of,” she explained.

“Then those things started breaking down. You saw huge outbreaks in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta where many people were sick and some people died.”

Prior to the rollout, Banerji added that the ICUs in Winnipeg were filled with First Nations people.

Infection rates and hospitalizations were also “spreading like wildfire” in Alberta and Saskatchewan, but Banerji said vaccination has made a huge difference. As more shots were administered there were fewer ICU admissions and cases began to drop.

“In this situation, we avoided catastrophes in many places,” Banerji explained. “It’s time to recognize that there are risks and prioritize these communities for interventions, like vaccines, in the future. But in collaboration with the community and the leaders.”

“Communities know what communities need”

First Nations, Inuit and Metis communities have been identified as Phase 1 priority groups in vaccine rollouts, partly because during the H1N1 pandemic, Indigenous peoples were disproportionately impacted by that virus.

There are a number of factors that leave certain populations vulnerable.

“We know that historically they’re at risk,” Banerji said.

“There are higher levels of chronic diseases, such as cardiac disease, diabetes, obesity and hypertension which are risk factors for COVID. We know that many Indigenous communities, especially remote communities, live in overcrowded conditions so if one person gets sick, it spreads quickly.”

Additionally, if patients require life support, that can cause further complications and there may be delays in getting healthcare. Banerji noted waiting for an air ambulance can take hours or days if the weather isn’t cooperating.

This is why she was just one of the many advocating for Indigenous communities, particularly those living on reserves, to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccines. Frequently meeting with elders, chiefs, experts and leaders to ensure the voices of communities were heard.

To get vaccines to remote areas, Dr. Richardson said partnerships were formed between governments in northwest Ontario, the province, leaders in the communities and Ornge, the air ambulance service, which played a key role in transporting healthcare professionals and vaccines to the regions.

“[This was done] to ensure that what happened in the community was done in a really good way, to meet the needs of Indigenous peoples on the ground,” Richardson said.

“Although many of us were on there as vaccinators or as healthcare leaders bringing our expertise from medicine and health, really I would say the expertise was on the ground from those leaders who knew their community members.

“They knew the families, they knew where people lived, and they knew where people were at in terms of how keen they were to get the vaccine.”

According to Richardson, that has led to incredible results — the biggest measurable outcome so far is the declining rates of COVID-19 on reserves. There were 72 cases reported across Canada last week.

“It’s a distinct population but it is a group that had very high rates of H1N1,” she said. “It’s an amazing story.”

A major takeaway for Richardson is the grassroots approach that was taken to make the vaccines accessible to as many people as possible.

The initiatives were led by Indigenous groups and leaders who were involved in developing the strategy to vaccinate people, deciding on the physical settings of where the clinics would be set up, working alongside healthcare providers who would be giving the shots and providing educational material to communities.

“Communities know what communities need. Each place is distinct, so you need to have Indigenous providers and leaders leading this work,” Richardson explained.

“That doesn’t mean that they do all of the heavy lifting and the delivery of the vaccines and that’s what I like about some of the examples that we’ve seen. You have Indigenous organizations and leaders who are guiding, leading and setting the strategy and the vision and you have partners who are bringing that vision to life and make it real.”

Both experts said this is an important story that needs to be highlighted and celebrated, especially since, as Richardson noted, Canadians aren’t used to hearing about the strengths and resilience of Indigenous peoples.

“If we can get vaccines into remote First Nations where people are still living with many structural barriers to health, like poor housing and in many cases poor access to clean water, we can do that across Canada,” she said.

“What we do when we see that, we see the cases coming down. It’s a story of hope here in communities where we don’t usually look to for guidance and hope. I really want us to reverse the way we think about our peoples.”

Vaccine Hesitancy

Late last year, as Canada and the U.S. awaited the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines, concerns were raised over possible vaccine hesitancy in some communities.

Indigenous and Black communities often dealt with racism and mistreatment in healthcare and experts knew it was vital to build trust and dispel myths to provide clear and transparent information to those who needed it.

“Having Indigenous leaders at the decision-making step and advocating for the vaccine, having clear and transparent communication was critical in getting community members vaccinated,” Banerji explained.

Despite concerns of hesitancy, there have been endless lineups at pop-up clinics around the Greater Toronto Area, where in many cases, the demand has been greater than the supply. Out of hundreds of people, Richardson said most decided to get the shot and only few chose not to.

“They have had really strong and important reasons why they chose not to do that,” she said. “We had amazing conversations with people who were concerned and needed good, up-to-date scientific information in a way that was accessible.”

In the rollouts up north, Richardson said the vaccine and information about the vaccine were readily accessible to any community member who wanted or needed it, with health professionals and experts set up in trusted locations and environments.

“I actually didn’t encounter hesitancy, I encountered gratitude,” she said. “When we look at the conversations around hesitancy, we need to reframe it completely. We need to understand what the barriers are.”