Separated by COVID, how music therapists helped Toronto veteran connect with wife in final weeks

Posted December 30, 2021 2:30 pm.

Last Updated December 30, 2021 4:55 pm.

When it comes to the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, seniors and those who stepped up to provide care for them have been among those impacted the hardest by its impacts.

“COVID has been such a hard time, such a dark time, anything that can lift your spirits is… valuable, very valuable,” Morris Adams, a 95-year-old resident at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Veterans Centre, said when asked to reflect on the past year.

Morris and his wife, Ruth Adams, are two of the more than 28,000 Ontario residents 80 and over who were diagnosed with COVID-19 since the pandemic began. Morris said he and his wife, previous residents in a Toronto seniors apartment building, contracted the virus after a PSW came to provide care to Ruth, who had dementia, despite enhanced screening and infection control measures.

Within a week, the couple got seriously ill and had to be rushed to Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre within a day of each other.

RELATED: Canada officially records more than 2 million COVID-19 cases since pandemic began

“They saved my life,” Morris said, noting he spent a couple of months hospitalized before going to a rehabilitation centre.

“I’ll tell you something strange. Sometimes I think about it and I haven’t figured it out yet… why was I spared? How was it I beat COVID?”

Ruth’s health, however, began to decline further after being diagnosed with the virus and required palliative care.

What followed for the husband and wife of 71 years along with their family marked a whirlwind of pain and emotion, but also the discovery of unsung heroes in Canada’s health care system and how they were able to unearth hidden joy.

‘She was the most amazing person’

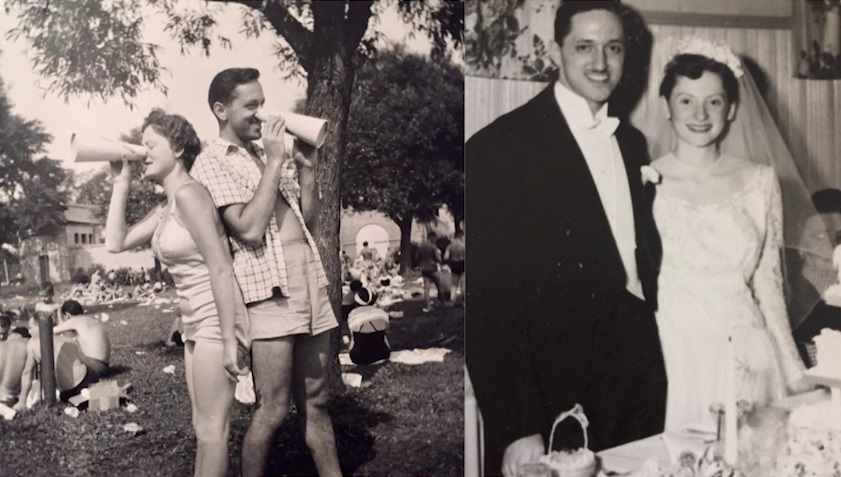

In order to fully appreciate the last chapter in Morris and Ruth’s story together, you need to go back — way back. Their courtship is one that goes back to the 1940s.

Morris said he and his cousin used to visit three synagogues in their Toronto neighbourhood and noted with the right suit, you could go into the social halls during a wedding after 9 p.m. and the families would assume you were friends of either the bride or groom. It was during one of those unknown weddings that Morris met Ruth.

“I wasn’t smart enough. I danced with her and left,” he recalled, adding it wasn’t too long when he came across Ruth and a friend sitting on a blanket at Sunnyside Beach while Morris and his friend were walking around “checking out the lunches and the girls.”

“This time I was smart enough to get her phone number and we begin to date.”

Morris, who was working at becoming a chartered accountant after a high school guidance counsellor said he should be a “professional” due to his high marks, was trying to make a life for himself after being drafted to serve in the Second World War at just 18. He trained to go to Holland at CFB Borden, but didn’t get deployed because the war came to an end — ultimately working at the base before being discharged.

Ruth and Morris Adams are seen in undated supplied photos.

He said their romance flourished, so much so that he told her he could only call her on weekends because their hours-long conversations during the week put him behind in his studies.

The pair married on June 4, 1950, and eventually settled in Toronto (Morris added their first house near Dufferin and Wilson cost just $11,000). He said as he worked as an accountant, he taught Ruth how to be a bookkeeper and noted she managed a dress shop on Yonge Street.

“She was very smart, very bright,” he said.

Fast-forward nearly seven decades and Ruth and Morris were still going strong. As Ruth’s health began to decline after having dementia for around a decade, Morris said it meant fewer vacations and outings. But they found ways to participate in activities together and one of the most meaningful ones was a choir Ruth belonged to, something perhaps a bit daunting for someone who wasn’t an active performer.

“She was a singer, she was a dancer, she wanted to make everybody happy, she was the most amazing person. Me I was the quiet introvert,” he said before being asked if he enjoyed the early days after joining the choir.

“Probably more so because I became a singer I never thought of it, never dreamed of it, and now I’m a recording artist and now I’m working on a second album.”

Reconnecting through the power of music

How exactly does a decades-long accountant become a recording artist? Well, it took being admitted to the centre (something Morris credited to his daughter Carolyn Adams-Lewis and her advocacy in early 2021 after being hospitalized) and a visit with its music therapist Teresa Ianni.

“I thought music might give him the opportunity just to kind of explore what had happened to him,” Ianni told CityNews.

“There was helplessness on his end.”

After Morris and Ianni met, she learned about Ruth, who moved into the centre’s palliative care wing weeks after Morris settled into a different wing at the centre. But COVID-19 protocols at the time meant Morris couldn’t be at Ruth’s bedside in person (eventually Carolyn was permitted to go an essential caregiver and sit with her mother on a regular basis).

“The next thing I know Teresa said, ‘Would you like to record a song?’ I’ve never recorded a song I said, ‘Sure why not’ … I never made an album before,” he said.

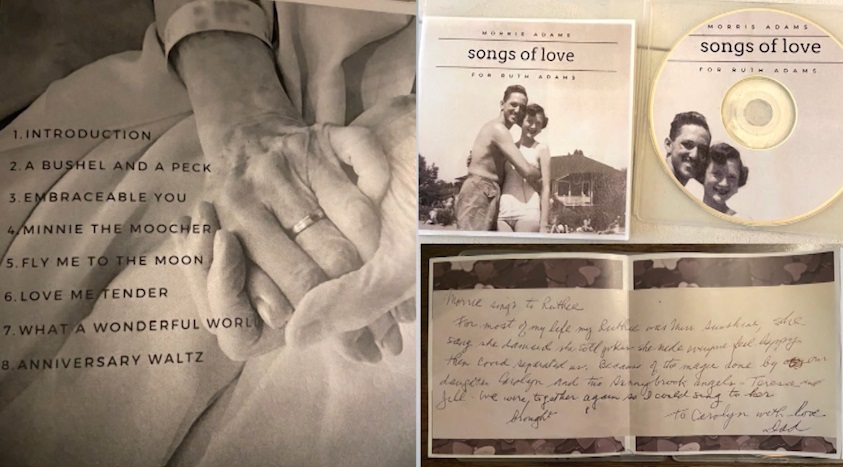

With the help of an iPad and the GarageBand app, Ianni and Morris went to work in one of the centre’s three music therapy studios. The selection of what would go on the album was particular, she said, adding Morris came with various songs she sang and he would review each word of the song’s lyrics to see if it fit.

“Every song he chose on the CD has a story behind it and a meaning for him behind it, and he is sharing that story with everyone now,” Ianni said.

Ruth and Morris Adams are seen in undated supplied photos.

The album, Songs of Love, has eight tracks including an introduction. Morris said four of the songs are ones they sang together and three were Ruth’s favourites, including Minnie the Moocher.

“Ruthie’s lyrics were even better than Cab Calloway’s lyrics when she would sing it. It’s a fun song. If people think taking drugs and doing cocaine is something that happened in the past few years, it wasn’t it’s a hundred years ago when Cab Calloway did this song,” he joked.

“You’ve got to imagine this vivacious, beautiful lady singing a song like that it’s kind of … um not exactly respectable, but it was fun. She was just a fun-loving person.”

Separated due to health protocols, Ianni and Ruth’s music therapist, Jill Hedican, coordinated times where Morris could sing to Ruth through iPads. Hedican held the device and even provided accompaniment at times. However, as Ruth’s health declined and it became harder to stay awake for longer periods of time, the CD was able to bridge the gap when Morris couldn’t be there virtually.

“The most important thing really in music therapy is to find the right music for the person you’re working with at that time,” Hedican said when asked about the importance of the therapy sessions.

“It can really open up opportunities for expression and ways for people to communicate what they’re feeling in a non-verbal way.”

Hedican and Adams-Lewis said even though she wasn’t able to recognize Morris’s presence in a conventional sense, there were subtle physical signs Ruth was enjoying it including gentle foot-tapping and occasional talking.

“I was really looking to see if she would open her eyes and recognize me. That didn’t happen, but I was hoping just hoping somehow she was experiencing me, that I was there,” Morris said.

The Songs of Love CD put together by Morris Adams and Teresa Ianni. HANDOUT

Toward the end of May with Ruth in end-of-life care, many at Sunnybrook worked to find a way to bring her and Morris together to celebrate their 71st wedding anniversary after being months apart. Using an empty room away from as many people as possible, on June 4 Morris was brought in and minutes later Ruth was wheeled in.

“I was able to see her, to touch her, to hold her hand, that was important very important,” he said.

Within days, Ruth died at the age of 93. She would have turned 94 on Thursday.

“Is it possible she waited until the anniversary? Anyway, it’s a story. It’s the most amazing story,” Morris said.

When asked to reflect on what it meant for her to see this journey at the centre unfold, Adams-Lewis said she is grateful to this day for the music therapy program.

“There are two pieces to medicine: The big piece we assume is happening. Doctors are amazing, the staff are amazing, they’re doing the best they can, but there’s another piece which is the human connection and contact and that was completely lost during COVID,” she said.

“It was through this connection, this music therapy connection… this was the gift. This was the means of connecting people who are separated remotely through music, through interaction.

“It felt like he could help, it was a means for him to become comfortable with the situation, to become comfortable with the fact my mom was dying, to learn how to say goodbye to her.”

Adams-Lewis said programs like music therapy should be treated as an essential service and broadened out in the health care system.

“It is an end-of-life experience I would wish on everyone. It is an exception and I would like to see it as a rule,” she said.

‘I’ve been given a second chance’

In the months since Ruth’s death, Morris said he’s settling into life at the centre. He said he’s embracing his role as the treasurer on the centre’s veterans’ council, emphasizing he wants to help and be “useful.”

“I need to be careful I don’t become a big shot and tell people what to do,” Morris said with a smile.

“I’m in a place surrounded by angels I can’t tell you.”

He said he just registered to get the latest electronic tax software so he can file taxes for himself, Ruth and a couple of clients he still has. Morris said after he recovered from COVID-19, he was glad he could still use his computer and read the newspapers.

No matter what Morris has on his ever-growing list of things to do, he said music will be front and centre. He and Ianni are finishing putting together a second album featuring 12 duet pieces with his granddaughter.

Suspended due to current COVID-19 restrictions inside long-term care homes, Morris said he’s waiting for the new Sunnybrook veterans choir to start up again. He noted there are eight members with hopes of adding more, and that four people are over 100 years old.

“So I’m the kid in this choir,” Morris joked, adding he wants to join the ‘100 club.’

“I’ll try to be a good boy and maybe I’ll get a solo.”