Racial bias reaches tipping point in Canada’s healthcare system

Posted December 4, 2019 12:42 pm.

Last Updated December 5, 2019 10:49 am.

This article is more than 5 years old.

Every year, millions of Canadians walk into a hospital or clinic to get treated, but as healthcare professionals themselves will tell you, not everyone gets treated equally. Studies and anecdotal reports have oftentimes demonstrated how racism — and conscious and unconscious biases — have impacted the level of care racialized communities receive.

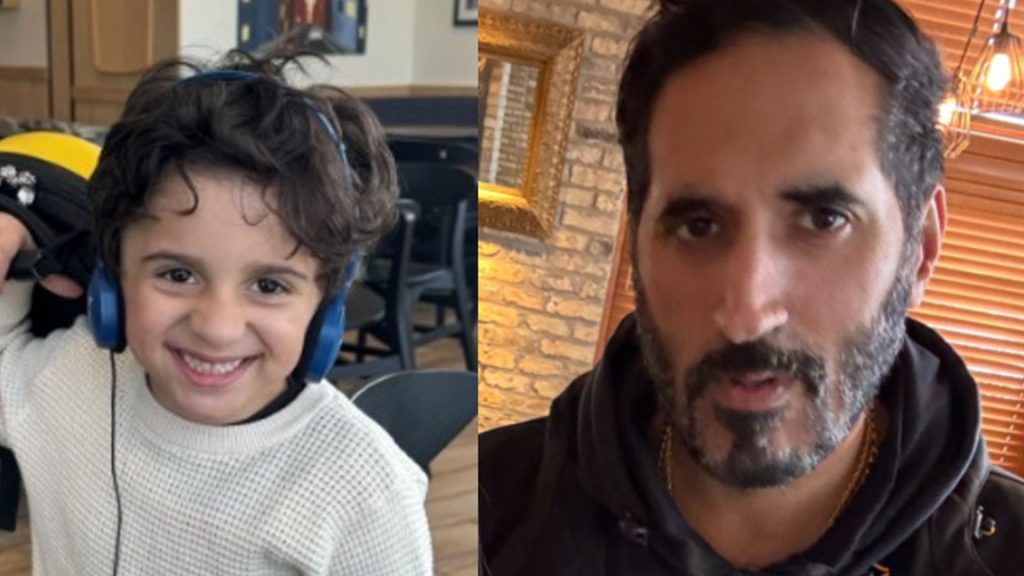

Imagine walking into a hospital in severe pain, but instead of receiving treatment, you get accused of faking your symptoms to get drugs. For an award-nominated Canadian rapper, it’s a reality he struggled through recently. John River, who’s real name is Matthew John Derrick-Huie, said he slipped through the cracks of the healthcare system, and was forced to wait weeks for an emergency procedure.

“Had I not been black, there was a much higher chance I would’ve gotten better treatment way earlier,” River said. “We have to ask, why did the medical system fail me in this fashion?”

Following a spinal tap procedure in December 2017, the now 25 year-old from Mississauga began experiencing symptoms of cerebrospinal fluid leak, but instead of getting the needed emergency procedure, he said he faced ongoing racism and discrimination minutes into walking into a hospital.

River said he visited more than five hospitals, and on separate occasions, he claims he was accused of being a drug user, a drug dealer, and imagining his symptoms, which included intense pain at the back of his neck, vision issues, loss of senses, and severe sensitivity to light. Despite the seriousness of these symptoms indicating a larger problem, River said it took him 60 days to get the emergency procedure. He believes he finally received the treatment because of his platform and his medical story going viral on social media. Read his full story here.

“What scares me the most is that there are a million other kids who aren’t rappers, who don’t have the following I did,” River said. “I know that because those same people tell me they now need help. That’s when I feel like the tide turned.”

There’s a John River everyday

Subjective and immeasurable symptoms, like the ones experienced by River, are more likely to be ignored if they are exhibited by people of colour and newcomers. Throughout the years, advocates and experts have long demonstrated the need to address racism in the healthcare system and the negative impacts it has on the health outcomes of racialized populations.

“Racialized populations, in particular black populations, are having the worst experiences in the healthcare system.”

Notisha Massaquoi, a health equity consultant, doesn’t know River or the circumstances surrounding his health, but said that unfortunately, his experience isn’t unique and is part of a challenge in a system ‘fraught with racial bias’.

“If someone came into my care, I look at them as someone who deserves to get the best, and deserves from me to do everything possible to figure out what’s wrong with that person,” he said. “On the surface that looks like a life that wasn’t valued, that was a life that was dismissed.”

Massaquoi, who is also the former executive director of Women’s Health in Women’s Hands, notes that there isn’t a system in place that is responsive to the needs of racialized communities and their negative experiences. More importantly, these conscious and unconscious biases have not been addressed effectively, and often times personal views are used to treat patients instead of professionalism. This in turn results in invalidating patients, a lack of empathy, and an inability to engage professionally when providing services to these communities.

“We’re finding that particularly members of black communities are going in spaces where they’re not only not well but they’re also experiencing racism, which is only going to increase issues around mental health and stress,” Massaquoi said. “I don’t think it’s any coincidence that black communities are experiencing higher rates of all the stress-related illnesses: diabetes, hyper-tension, heart disease, which are all preventable.”

Massaquoi adds that these inequalities start before patients even enter healthcare facilities. In a city as diverse as Toronto, there are still barriers to accessing healthcare. Communities that have racialized populations have the least amount of services in their neighbourhoods.

“Racialized populations, in particular black populations, are having the worst experiences in the healthcare system,” Massaquoi said. “Their issues aren’t being addressed fast enough, timely enough, appropriately enough and therefore we’re having more premature deaths, and higher rates of illnesses that should be preventable.”

That lack of access sets the tone for these patients and their abilities to get treated, and they are also less likely to seek out medical attention. If the issues aren’t being addressed, then that results in more premature deaths and higher rates in illnesses that are preventable.

“What we’re seeing is that black populations, in particular, have the highest rates of poorer outcomes in this city,” Massaquoi said.

There are examples of these negative health outcomes. For instance, diabetes rates are higher among the black and South Asian communities, as well as communities that have higher populations of new immigrants.

In looking at the highest rates of HIV prevalence in Toronto, black communities are over-represented. Breaking the numbers even further, Massquoi said that black women make up almost 70 per cent of all new HIV infections per year, yet the healthcare industry hasn’t been responsive to the epidemic.

“The system hasn’t created prevention strategies that can reach these populations,” Massaquoi said. “The programs that we have to prevent HIV infections are not being directed to the population that is at highest risk. That’s racial bias, that’s when we’re getting into racism. Where you can watch a population struggle with an epidemic and not redirect resources to specifically look at the issues that we’re dealing with.”

Race-based data collection

Back in September, the Toronto Police Services Board took a historical step, and approved the collection of race-based data. Massaquoi, who is the co-chair of the anti-racism advisory panel of the board, states the healthcare system has already started setting the foundation to do the same, but is moving at a much slower pace.

“If we don’t understand what health experiences racialized communities are having, we’re not going to be able to treat people effectively.”

Socio-demographic data would allow for healthcare professionals to have a stronger understanding of prevalence rates of particular illnesses that impact certain communities, and also determine if there are certain populations who aren’t regularly accessing healthcare services. This type of data will collect patient details, including; age, racial identity, languages spoken, education level, and income levels.

“We are all under a mandate that’s about to be legislatively rolled out, where all public services will have to start collecting race based data,” Massaquoi said. “If we don’t understand what health experiences racialized communities are having, we’re not going to be able to treat people effectively.”

According to Massaquoi, there are already clear indications that this type of demographic data collection is effective. For example, researchers have been able to identify how certain populations have higher rates or are more vulnerable to certain diseases, like different types of cancers. It also has the ability to break down the numbers even further, based on a number of identifiable factors. For instance, when looking at the number of new HIV infections, the data suggested that 80 per cent were male and only 20 per cent were female. But when that data was further broken down based on gender, black women were impacted overwhelmingly.

“When you unmask data so that it’s no longer colour blind, you get to see the nuances for specific communities and what the needs are, then you can tailor your healthcare services across the board,” she said. “Colour blind healthcare services will only serve white populations.”

The process was started by the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network, who have been trained and developed tools to collect race-based data. But Massaquoi said there needs to be the political will to maintain the process, and the training and the mandating of it. A spokesperson wasn’t available for an interview, but directed CityNews to this website, which provides the foundation into how hospital sand community health centres have been collecting demographic data. The Measuring Health Equity initiative was developed by the Sinai Health System. The standardized set of eight demographic questions were standardized back in 2014, but the data collection so far only pertains to hospitals in downtown Toronto.

“It’s very voluntarily managed at this point of time,” she said. “There has to be the understanding of the necessity of it and the importance of it, in terms of how are we going to provide better service to racialized communities in this city and the province as a whole.”

Government responses

In December 2017, Ontario’s then Liberal government released a scathing report — The Clinical Handbook for Sickle Cell Disease ( SCD) Vaso-occlusive Crisis — that details the challenges patients with sickle cell disease faced when accessing healthcare. SCD is most prevalent in black communities, where patients often times experience pain attacks without warning.

The report detailed how clinicians and administrators recognize that these patients oftentimes experience racism when seeking out medical attention, a clear indication of the systematic issues that have had detrimental impacts.

“Why don’t we have a center of excellence looking at sickle cell treatment and care, in city that has the highest rates of black populations in the country?” Massaquoi asked. “Racial diversity has to come in play here.”

The Public Health Agency of Canada notes that the collection of race-based data at hospitals “falls under provincial and territorial jurisdiction, and provincial and territorial governments are responsible for the management, organization and delivery of health care services for their residents.” A spokesperson notes, however, that the government recognizes that “race/racism as one of the main determinants of health, and there is growing evidence of race-based discrimination in the Canadian healthcare system.”

The Ministry of Health and Long-term Care wasn’t able to provide CityNews with an interview, but a spokesperson said the government is committed to ensuring all Ontarians have access to the care they need. However, when asked about data collection and why it wasn’t a requirement for the health sector, a response was not provided. CityNews has once again followed up, asking the ministry for a response into whether or not the government has plans to collect data. In the initial statement, the spokesperson states the government has been encouraging providers to improve the health of all populations, and reduce disparities among different communities.

“As part of health system transformation, Ontario is building equity considerations into the new Ontario Health Teams model, which will encourage providers to improve the health of an entire population, reducing disparities among different population groups,” Anna Miller wrote in an email. “The Ministry of Health has also identified equity as a key component of quality care and developed the Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) tool to support improved health equity, including the reduction of avoidable health disparities between population groups.”

Leading the way

There are clinics and health facilities in Toronto, including Massaquoi’s former place of work, who have already implemented measures in addressing racial inequalities in healthcare, while also reducing barriers to members of racialized communities. Some of these facilities have been collecting race-based data for over two decades, prioritize their messaging to clients, prioritizing fair treatment and appropriate care.

“What you see happening in those centres is a very deliberate way of delivering service so that the service providers come from those populations for example, and if they don’t, they’re allies, who have been trained to work effectively with the populations,” Massaquoi said. “We understand what the prevalence rates are for our communities in particular to certain health issues, and therefore we develop expertise and programs in those areas.”

But these centres treat a very small portion of the population, and don’t have enough resources to serve every racialized community and addressing the issue of racism as a whole. That’s why, Massaquoi said, early intervention is key so that individual service providers aren’t left to deal with the equitable health system on their own. For instance, assessing what schools are teaching future healthcare professionals, so that graduates are educated prior to getting indoctrinated in these biases.

Then there are also questions as to whether or not medical facilities, including hospitals, employ a diverse range of professionals at all levels, especially in leadership roles.

“The formation of it starts with the lack of information,” Massaquoi. “We have health education systems that are teaching people to engage in healthcare with only white populations.”