Jury deliberations begin in trial of man accused of killing Toronto cop

Posted April 18, 2024 2:35 pm.

Last Updated April 18, 2024 5:45 pm.

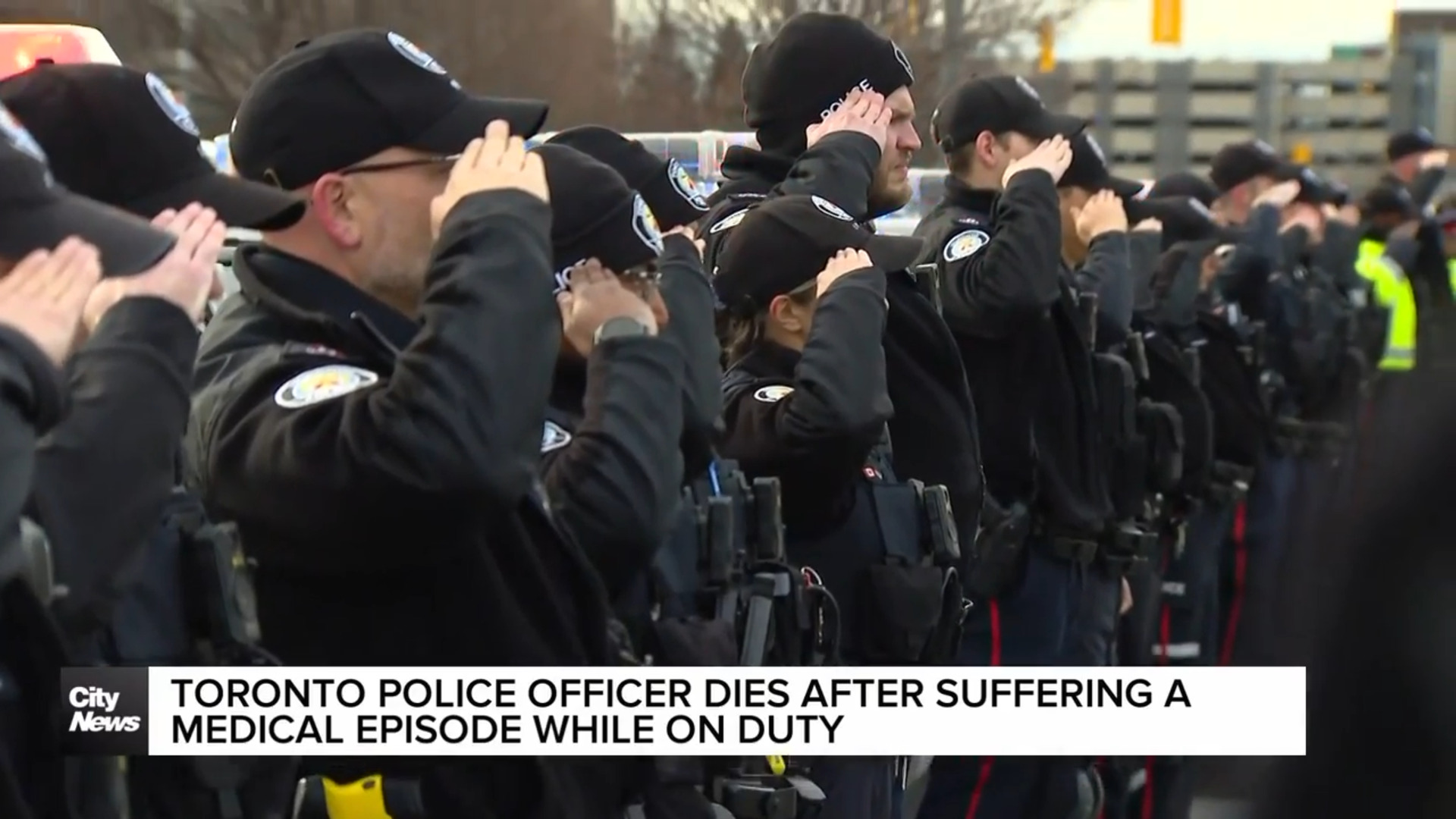

The fate of a man accused of fatally running over a Toronto police officer is now in the hands of the jury.

Umar Zameer has pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder in the death of Det. Const. Jeffrey Northrup.

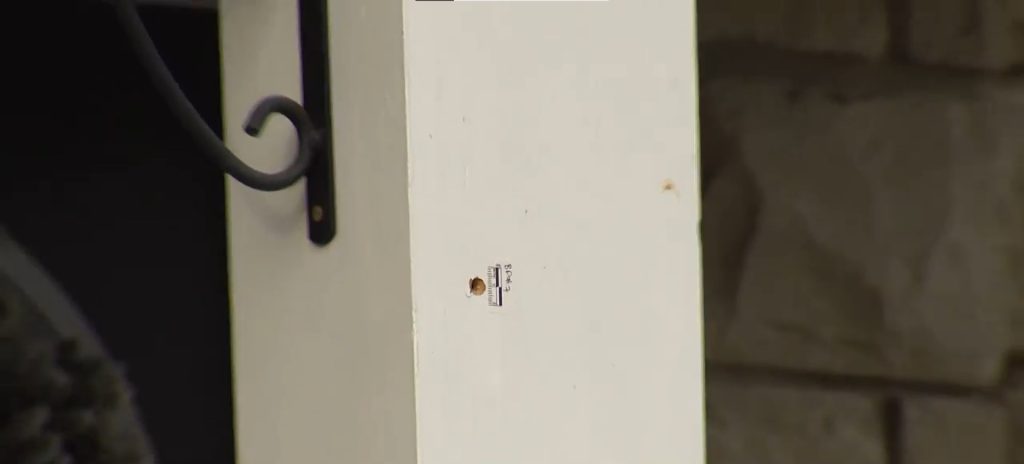

Northrup died on July 2, 2021, after he was hit by a vehicle in an underground parking garage at Toronto City Hall.

Ontario Superior Court Justice Anne Molloy spent the day instructing the jury on four possible verdicts in the trial: first-degree murder, the lesser included offences of second-degree murder or manslaughter, or not guilty of any offence.

She says that in order to find Zameer guilty of murder, jurors must find beyond a reasonable doubt that he intentionally ran over Det. Const. Jeffrey Northrup.

Whether it is first- or second-degree murder depends on whether jurors believe beyond a reasonable doubt that Zameer knew Northrup was a police officer acting in the course of his duties.

Under law, the murder of a police officer acting in the course of their duties is automatically first-degree, so long as the person accused knew or was wilfully blind to that fact.

Molloy told jurors there are three pivotal issues in the trial: whether Zameer knew Northrup was a police officer acting in the course of his duties, whether Northrup was standing in front of Zameer’s car when he was hit, and whether Zameer knew he had run someone over.

At the heart of the case is whether Zameer meant to hit Northrup – or even knew it happened – and whether he knew Northrup and his partner, who were in plain clothes, were police officers.

Prosecutors say Zameer drove directly at Northrup, who they say was standing at the time, and made deliberate choices to drive dangerously while there were people nearby.

The defence argued Zameer did not intend to kill anyone and behaved reasonably in the face of what he thought was an imminent threat to his family as two unknown people rushed up to his car and began banging on it.

Zameer testified he did not see anyone in front of his car as he was driving forward. Two crash reconstruction experts, including one called by the Crown, told the court they concluded Northrup fell after the car made glancing contact with him while reversing, and was on the ground when he was run over.

The expert called by the defence said Northrup would have been in the car’s blind zone and not visible to Zameer when on the ground.

Unbeknownst to the jury, the judge overseeing the trial repeatedly raised concerns over the prosecution’s changing theory of what happened the night the officer died, with the Crown ultimately dropping one of the alternate theories it planned to present in closing arguments. The theory – that Northrup was “clearly visible” to Zameer when he was hit regardless of his position, which itself is in dispute – was abandoned after the judge said she was struggling to understand it.

Here are some other things jurors didn’t hear about the case:

Bail judge found prosecution had “weak” case for murder

Zameer was released on bail in the fall of 2021, but the reasons for his release and the evidence and arguments presented in court could not be disclosed until now. Much of the evidence, including Zameer’s account of what happened, has emerged at trial, but the bail judge’s reasons have not.

In determining whether to release someone on bail, judges must consider whether that person might flee to avoid prosecution, whether they pose a threat to public safety, and whether their release would erode the public’s confidence in the justice system.

In her ruling, Ontario Superior Court Justice Jill Copeland, who is now an Appeal Court judge, said the risks related to flight and public safety could be mitigated through Zameer’s supervision plan and a driving ban. As for public confidence, she said the test is based on an informed member of the public – that is, one who knows the facts of the case.

Copeland found that the prosecution’s case for murder was “weak,” and its theory of liability failed to “consider objectively all of the evidence available at this point.” She specifically pointed to the absence of any evidence regarding a motive as a “significant weakness” in proving Zameer had the intent to kill.

“The Crown’s theory – that Mr. Zameer, who the evidence supports was out for a normal family evening with his pregnant wife and young son, who has no criminal record, who has a good work and education history, suddenly decided to intentionally kill or cause bodily harm that he knew was likely to cause death to a police officer – runs contrary to logic and common sense,” the judge wrote.

She found the Crown had a “reasonably strong” but not “overwhelming” case for manslaughter. Even if jurors did not believe beyond a reasonable doubt that Zameer committed murder, they would have to decide whether his manner of driving was unreasonable to the point of manslaughter through criminal negligence, she wrote.

Judges assess the strength of the Crown’s case at the bail stage only as it relates to the criteria for release. They may not have access to all the evidence that will be available at trial and the evidence they do have is not tested in the same way it is at trial.

The judge’s instructions on possible police collusion

Northrup’s partner, then-Det. Const. Lisa Forbes, and two officers who were at the scene in an unmarked police van, constables Scharnil Pais and Antonio Correa, all testified they saw Northrup standing in the middle of the laneway with his hands up when he was run over.

There is no evidence as to when Forbes wrote her notes on the incident, but Pais and Correa told the court they wrote theirs on Aug. 4, more than a month later. Court has heard all three gave a statement to police at various times on July 2, and Pais and Correa did a walkthrough of the garage together on July 20. The officers have all maintained they did not discuss their evidence with anyone.

One of the officers who arrived at the scene during Zameer’s arrest testified that he, Pais, Correa and two other officers wrote their notes at the same time, in the same room. Forbes was not present.

In the absence of the jury, lawyers discussed a section of Ontario Superior Court Justice Anne Molloy’s proposed instructions in which she addresses the possibility of collusion between the officers.

Prosecutor Karen Simone asked Molloy to make a distinction for Forbes, since the officer wasn’t part of what the judge called the “note-making party” or the tour of the garage. Simone noted Forbes gave her statement on a body-worn camera 17 minutes after she called 911, before she saw Pais and Correa again and before the two officers gave their statements to police.

Such a distinction would allow the jury to assess Forbes’s credibility and reliability independently of the other two officers, she argued.

But Molloy said she couldn’t draw that line because if there was collusion, it happened after Forbes’s version of events spread.

“She has given a version of the events that didn’t happen, and now two other officers have the same version somehow. That’s bizarre,” the judge said.

“Saying she gave a statement at the time, and she gave statement at the hospital, and she gave a statement at the (police) station just means she gave a lot of statements, and a lot of people know what her version is.”

The judge noted her proposed instructions to the jury didn’t suggest how the officers got to the same version of events, but that she also “can’t not tell them they have to consider collusion.”

“(And) I can’t tell them, ‘but Officer Forbes wasn’t part of it,’ because I don’t know that,” she added.

The expert’s outburst

The Crown at one point considered suggesting to jurors that a crash reconstruction expert called by the defence may have been biased in his opinion after he lashed out during cross-examination.

Barry Raftery aggressively accused the Crown of misleading the jury and was reprimanded by the judge for his tone. Molloy later told the jury that prosecutors had not been misleading.

During legal arguments in the absence of the jury, Molloy acknowledged Raftery was “angry and hostile” during the exchange, and said that if prosecutors were planning to raise the possibility of bias, she would give jurors instructions on that issue.

However, the judge said she would also have to include the broader context of the outburst. She noted Raftery’s testimony “started out on such a bad foot” after the Crown accused him of having been criticized for his testimony in another case, which turned out not to be true, and did not give him the opportunity to respond. The judge told the jury at the time that it was a mistake and that Raftery had not been criticized by the court in that case.

In the end, Simone said she would highlight areas of Raftery’s evidence that the Crown believes are “problematic” in her closing submissions to the jury without suggesting the expert was biased or referring to what she called his “very inappropriate and unprofessional outburst in court.”