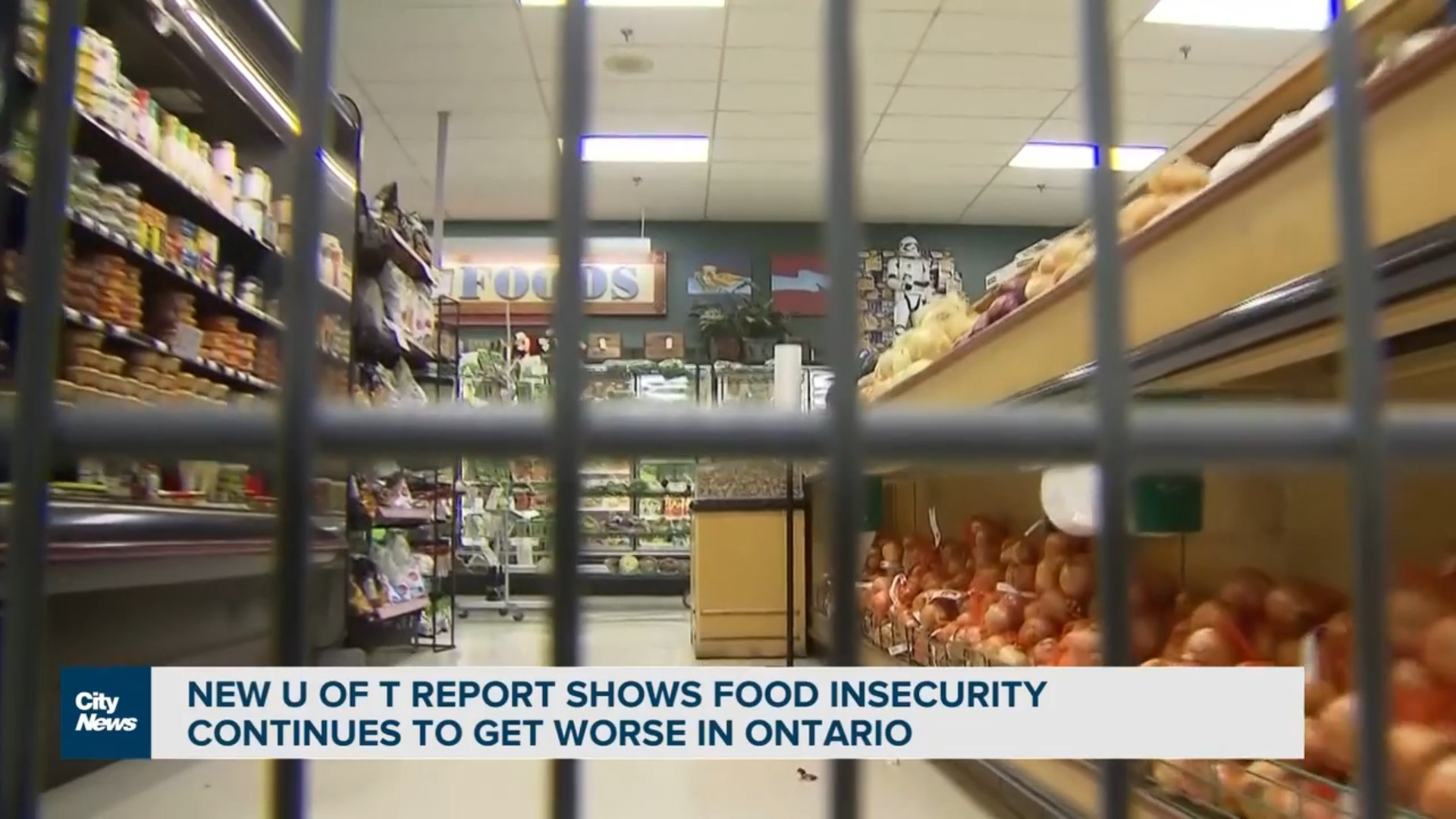

Food insecurity continues to get worse in Ontario and across Canada, study shows

Posted November 21, 2023 8:20 pm.

Last Updated November 21, 2023 8:47 pm.

As so many Canadians have been battered with inflation and soaring costs on a wide range of goods, a new study out of the University of Toronto is showing food insecurity is getting worse in Ontario and other provinces.

Researchers at PROOF, which works to provide policy recommendations to deal with food insecurity, found 18.7 per cent of Ontario households were dealing with food insecurity. That figure is 2.6 per cent higher than 2021. Roughly similar numbers were found in other provinces.

“Food insecurity, we’ve known it’s been around for a long time and the fact that it’s getting worse now is something that I think all governments should be paying attention to,” Tim Li, a research program coordinator, told CityNews on Tuesday.

“What we saw when we compared the previous year to this year is a majority of the increase of the additional households that were food-insecure were in Ontario.”

According to figures provided by PROOF, 2.8 million Ontario residents are living day-to-day with food insecurity and one in four of those people are children. He said it’s fueled partly by inflation along with rent and mortgage increases.

Li said job incomes largely aren’t cutting it when it comes to making ends meet for many.

“In Ontario, about 60 per cent of the food-insecure households their main source of income was employment, wages and salaries. So yeah, having a job doesn’t really guarantee a household is kind of food-secure,” he said.

“What’s important is both the amount of money that job provides, the income, but also stability, right, so we have a lot of precarious work and that’s a real issue.”

In the 2022 report, PROOF researchers also examined the racial disparity in Canada. They found 19.3 per cent of children living in food-insecure households are white. The statistics jumps among racialized families where 46.3 per cent of children who are Black and 40.1 per cent of children who are Indigenous live in food-insecure households.

“I think this really speaks to systemic racism and colonialism,” Li said.

“I think it speaks to some of the challenges within this regarding discrimination within labour market, within the housing market, and all the different ways that contribute to barriers to health and wealth acquisition. It makes it harder for these groups to really kind of keep up with everything going on.”

The observations found by PROOF were echoed by staff at the Daily Bread Food Bank in Toronto.

“We know that systemic racism directly leads to the disparate rates. We see food insecurity so we do see an over-representation of racialized communities,” Talia Bronstein, the food bank’s vice-president of research and advocacy, said.

RELATED: As communities struggle with food insecurity, study shows impacts on youth mental health

Daily Bread is among the agencies in Toronto that have been struggling to keep up with an unprecedented demand for services. Staff said it’s estimated one in 10 in Toronto are using food banks. In 2019, they saw approximately 65,000 visits from people a month but now that number has jumped to 270,000 visits monthly.

“It took us about 30 years to go across the one-million mark in terms of food bank visits in Toronto. It took us two years to then cross the two-million mark and it will take us one year to cross the three-million mark,” Bronstein said.

“We are not set up to be the default food provider to the whole city. We are an emergency response. We are meant to be a short-term relief for people who are experiencing something catastrophic in their lives, but the reality is people have to rely on food banks every single month to make ends meet because they are just never able to afford their expenses with their income that they had just the cost of living alone.”

She added the agency now buys $22-million worth of food annually whereas in 2019 it was $1 million.

The organization has appealed for financial donations and volunteer assistance in response to the demand, but Bronstein said what’s needed more than ever is advocacy.

“We need every person living in Canada to raise their voice and say this is unacceptable. We need government to take more action … food is a human right,” Bronstein said.

Both Bronstein and Li said every level of government is failing. They said decent work, affordable housing and income supports need to work in tandem and be stronger — not just for families, but also for single people and people with disabilities.

“What frustrates me so much is that we see time and time again these trends that food insecurity is increasing, increasing, increasing,” she said.

“We have very clear, very realistic solutions to these problems.”

She and Li pointed to the federal Canada Child Benefit and said it has reduced food insecurity among children as well as income support programs for seniors.

“What about the rest of Canadians?” Bronstein said.

“It’s unfortunate that not more has been done with [the Canada Child Benefit] in recent years to kind of address the food insecurity but also kind of help buffer against rising cost of living,” Li added.

As for what next year’s report might hold for Ontario and beyond, Li wasn’t optimistic.

“I think things are definitely going to be worse based on what we’ve seen,” he said.

“The fact that cost of living has gone up, incomes haven’t gone up to meet the cost of living and the types of interventions that we’ve seen throughout the year — things like the one-time (federal) grocery rebate, similar provincial kind of affordability measures — they’ve been very small, time-limited and they don’t really address kind of the underlying long-term chronic income and adequacy that’s driving this problem.”

Meanwhile, Li said governments need to rethink tackling food insecurity, adding access to healthy foods and stronger incomes have preventative health and financial benefits.

“One of the main things that we’ve been able to do with our research is look at the health outcomes related to food insecurity and look at health-care use and what we’re seeing is that for a household to be food insecure, its members are very likely to be in poor health, rely on the health-care system more, cost the health-care system more,” he said.

“These numbers are … a strong predictor of health and if we start paying attention to these numbers and start thinking about how can we make our existing policies or new policies respond to these numbers better, I think we’d be in a much better place.”