Concerns over classroom violence remain top issue for Ontario teachers

Posted September 19, 2023 5:46 pm.

Last Updated September 19, 2023 5:55 pm.

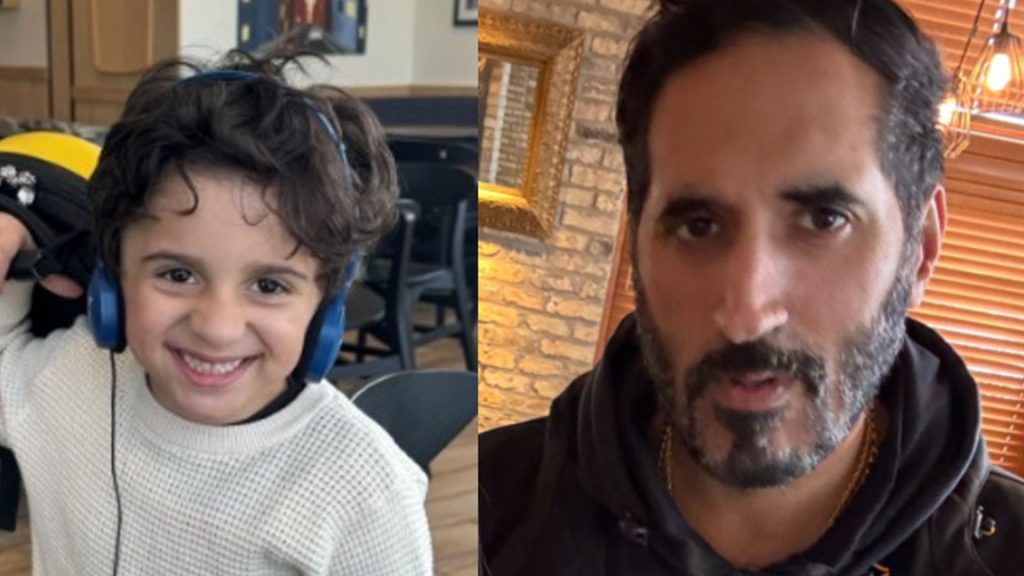

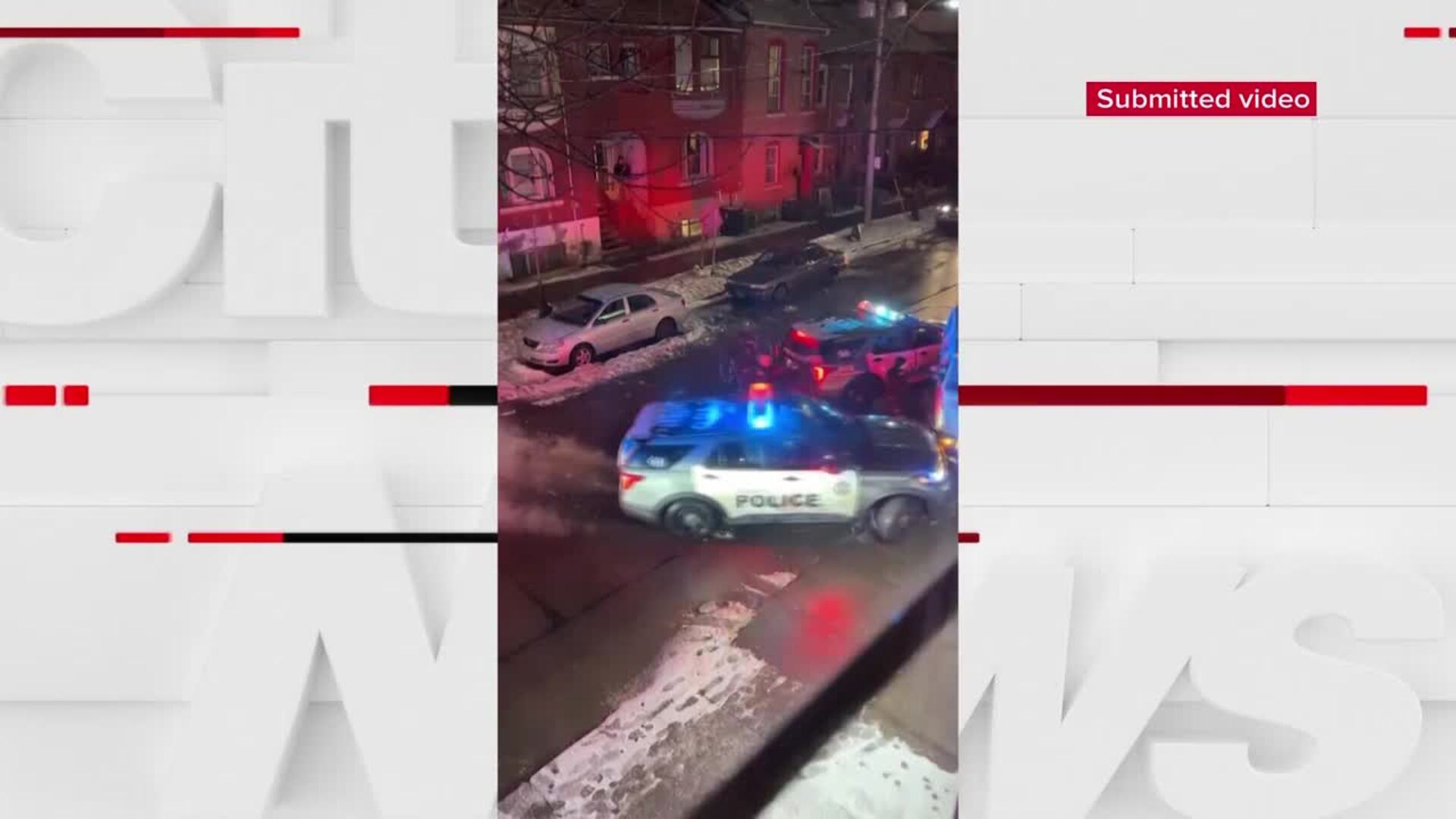

The assault of multiple staff members and a student at an Oshawa school on Monday is once again highlighting the issue of violence in schools, which remains a top concern for teachers in ongoing bargaining with the province.

The president of the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation (OSSTF) told CityNews the worry is that there are not enough trained professionals to support students with various needs.

“The teacher should not be filling in as a physiologist or a child and youth worker or social worker in the absence of those trained professionals being available,” OSSTF President Karen Littlewood said.

In many cases, teachers need crisis intervention training before stepping in to help stop behaviour that could lead to injuries.

“It becomes really challenging because people want to do the best by students.”

The Durham Catholic District School Board (DCDSB), which oversees Sir Albert Love Catholic School in Oshawa where three teachers and a student were assaulted, says it would have had staff on-site trained in violence threat risk assessment.

“It could be as simple as a teacher reaching out to the staff in the building who do have the training,” Superintendent of Education Paula Sorhaitz said in an interview.

Sorhaitz declined to confirm whether that was the case on Monday, citing the police investigation.

The Ontario English Catholic Teachers’ Association (OECTA), which represents the teachers assaulted, could not comment on the specifics of the situation but noted there are “very serious concerns” about the gaps between the obligations under the Health and Safety Act covering workplace violence and the implementation in school boards across the province.

“I would suggest that the school boards are not properly equipped to deal with their obligations under Health and Safety to keep the workers safe,” said OECTA President René Jansen in de Wal. “How do you respond, and what do you have in place to deal with the violence? Certainly, there is a gap there so it leaves students and their teachers vulnerable.”

The unions have blamed the rise in violence on a lack of funding and resources for public education. A statement from a spokesperson for Education Minister Stephen Lecce reads in part, “Our government continues to take decisive action to reduce violence in schools. That is why we are investing nearly $700 million more in additional funding this school year, including $24 million on enhancing school safety and the hiring of nearly 2,000 more front-line staff.”

Violence in the classroom ‘not a new thing’

“It’s not a COVID thing, it’s not a Toronto thing. It’s not a high school thing. This has been an issue for many years, but the incidents seem to be increasing,” Littlewood said.

A survey conducted earlier this year for the union representing public elementary teachers found 77 per cent of its members have personally experienced violence or witnessed violence against another staff member. The results revealed two-thirds of members reported the severity of violent incidents has increased in their schools, and educators working with younger students are more likely to experience violence.

When there is a violent incident at school, the unions say staff are reluctant to report it because they don’t have confidence in the system.

“The tracking and reporting of instances of violence in schools is very problematic,” Jansen in de Wal said.

“The workers have to have confidence in the system that if they make a report of violence or if they express concern for their working conditions, that it is going to be addressed and quite frankly that’s not the case in so many situations,” added Littlewood.

“So you do have people that have anxiety about entering the school building.”