Toronto Police expanding mobile crisis teams

Posted April 28, 2021 6:46 pm.

A Toronto police program that pairs officers with mental health nurses is expanding.

At a time some are questioning whether police should be the ones responding to mental health calls, changes are in the works for the mobile crisis intervention unit.

“The expansion is for the community and for the mental health community,” said Deputy Chief Peter Yuen, of the Toronto Police Service.

Last year, the mobile crisis intervention teams (MCIT) responded to 7,500 of the about 40,000 annual person-in-crisis calls. This year, the partnership between police and local hospitals will be available for more hours every day.

“We’re expanding from 10 hours on the road a day to 14 and a half hours,” said Leah Dunbar, project manager of the mobile crisis intervention team at Michael Garron Hospital.

There will also be 12 teams on the roads for seven days a week, plus a downtown team four times a week.

“We’re able to see more people and provide them with those supports,” said Dunbar.

With the expansion, the teams are expected to handle more than 11,000 calls.

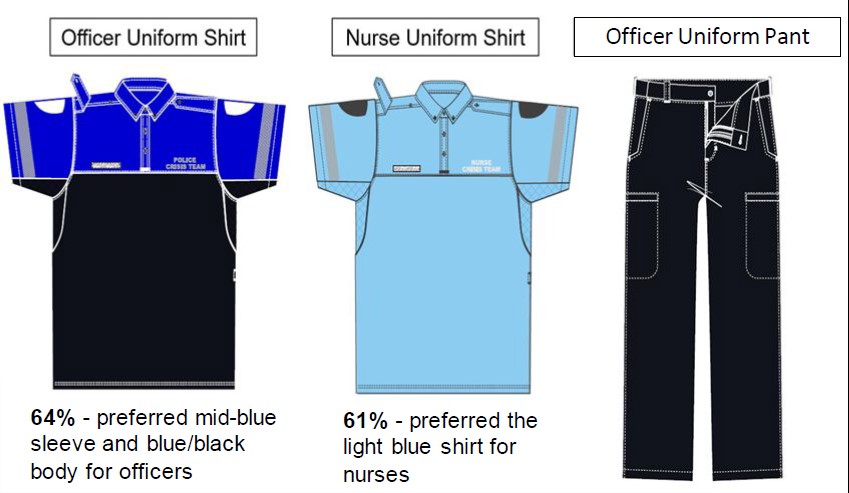

The teams are also planning a new look, including uniforms and vehicles that look less like traditional police cars. Yuen says the changes are meant to take the stigma away from community interactions with crisis teams.

“These are things that were asked of us from the community,” he said

The MCIT will have new uniforms and vans designed to look less like police cars. Credit: Police Services Board

The expansion comes as calls to defund police have intensified.

Police in the GTA have been scrutinized for their handling of mental health calls, which in some cases have ended with officers killing people in crisis.

“We also understand mental health response shouldn’t solely be a police-led type of incident,” said Yuen. “We’re the only service available 24/7, certainly we support non-police responses and we will do everything we can to collaborate with other agencies.”

Yuen says the force is working with communities, adding that the service shifted existing funding into this expansion. MCIT training has also doubled to 80 hours, with an emphasis on de-escalating tense situations.

“We’re able to include things such as autism spectrum disorder, major mental health disorders, trauma-informed care, patient advocacy,” said Dunbar. “We’ve really been able to enhance the course.”

“We can’t ever have enough communication skills,” said Yuen. “And also understanding intersectionality of racialized communities, anti-black racism, anti-indigenous racism, implicit bias — these are all the new things we have included in training.”

Yuen also said that the MCIT will help connect people to community-based services and programs, instead of diverting them to hospitals, which are currently overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients.

The police service is also launching a downtown 9-1-1 pilot project, hoping to centralize access to community agencies. Yuen is optimistic that at times, officers won’t be required at calls.

“It will be a collaborative effort between 9-1-1 call takers and crisis workers to determine how these calls should be triaged and who should be attending,” explains Yuen.

More details on the 9-1-1 pilot are expected to be released in May.