High cost of water plant connection blocking Indigenous residents from accessing clean water

Posted August 31, 2022 11:07 am.

Last Updated August 31, 2022 1:47 pm.

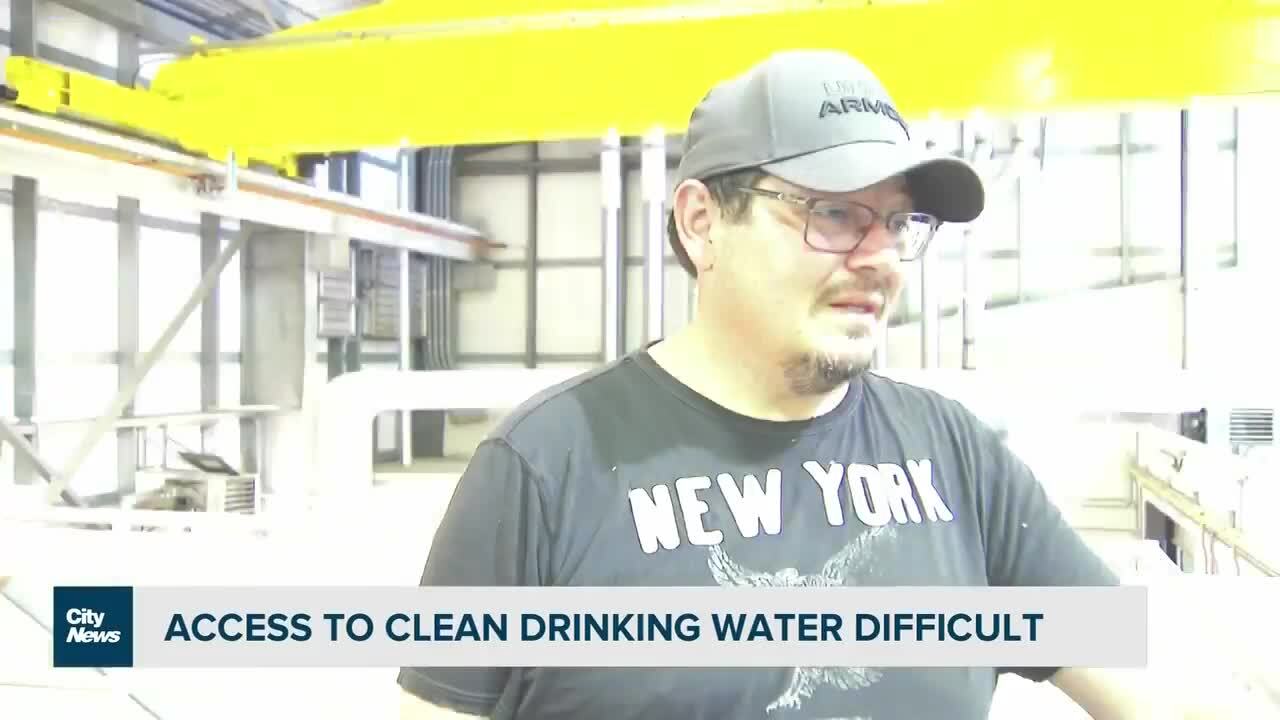

In Six Nations of the Grand River, just two hours away from Toronto, more than 80 per cent of households don’t have direct access to clean drinking water, despite a multi-million-dollar water treatment plant built less than a decade ago.

“We’re doing our best to progress our community as best as we can,” said Chief Mark Hill. “But there comes challenges, and one of those challenges is the access to clean drinking water, potable water.”

Six Nations of the Grand River’s main source of water is the Grand River. In 2013, a water treatment plant was built on the reserve. The $41 million project was partially funded by the federal government, with the local council contributing about $16 million. When it opened, the builder noted it could treat 4,050 cubic meters of water per day, the equivalent to 1.6 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

After a round of further expansion work in 2018, the plant serves about 570 homes out of 3,100 in the community, and two schools.

A major barrier to having everyone connected to the filtration plant is the cost of the pipe network needed to do it. Hill tells CityNews it would cost almost $200 million to fully pipe and connect the remaining homes.

Those not connected to the water system rely on cisterns, underground containers that can be filled with water that’s trucked in. Other residents receive their water from wells. Both sources are open to contamination, so residents buy bottled drinking water.

RELATED: Many Six Nations of the Grand River residents live without direct access to clean water

Hill estimates it costs a household an average of $2,500 for a year’s worth of water.

CityNews toured the water facility with local resident and assistant water plant operator Dan Joseph. He explained that there’s been a water plant on the reserve as far back as the in the 1960s, and adds the current plant is effective.

“We keep it well below the ministry standard. They’ll allow a certain amount [of contaminants]. We stay way below that,” he said. “We know that the water is getting really clean.”

Joseph himself is not on the current distribution network, and instead buys bottles of water to consume. His home operates on a well, but the household only uses that water to wash up.

“We don’t drink it. We don’t use it for cooking at all,” he said. “So hopefully soon we’ll be on the water distribution.”

Hill said the price of connecting a home to the treatment plant depends on where the house is located.

“Different circumstances will define the cost,” he said. “What we’re seeing from just our phase one range: from $4,000 to $15,000 per home. And that’s just the connection.”

Under its water servicing strategy, this year the reserve is subsidizing eligible residents’ connections, at a cost of $80 million to the community. Officials estimate another phase of the strategy, for homes on the southern portion of the reserve, would cost $75 million.

The water servicing strategy notes that there isn’t “stable or predictable” funding from the federal government on water projects, forcing the community to apply annually to local trusts to fund watermain expansion.

“The government, all the time, speaks of reconciliation and [for] this government, there’s no more important relationship than the relationship with Indigenous peoples,” he said. “But yet we’re still and we’re just we’re the largest reserve and we still have people living in poverty. We still have people with no running water into their homes.”

Reserve leaders have had meetings with ministers and government officials at the federal and provincial level, Hill added, and have also connected with municipal partners to find solutions.

In 2019, the community partnered with the federal government, the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation and Haldimand County to connect homes living on the border between the two indigenous communities to Haldimand’s water system. Indigenous Services Canada contributed $4.7 million toward the project.

“Minister Hajdu remains in regular communication with Six Nations of the Grand River as we work in partnership to find long-term solutions to ensure access to clean drinking water in their community,” read a statement from the office of the Minister of Indigenous Services, Patty Hajdu.

Other projects are in the works, Hill said.

“We’re looking to a partnership with the municipalities of Haldimand, as well as Norfolk, to look to at least the south side of our territory coming down the highway so that we can start to maybe get creative in that way in, have other opportunities of different sources of water,” he explained.

Six Nations has also been working with the Dreamcatcher Foundation to bring temporary water filters to homes currently not connected to the water treatment plant as a short-term solution for clean water.

“Our source of water comes from the Grand River. But maybe there’s an opportunity to have lake water for some of the homes, I’m not sure,” added Hill. “What I do know is we have to get this done in a timely manner because it’s long overdue.”

In a new series, CityNews will be talking to Six Nations community leaders, residents and water keeper Autumn Peltier about efforts to get every resident access to clean water and why this issue is proving so hard to solve, Canada-wide.