Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation highlights role of art in the science of treating cancer

Posted December 1, 2022 12:55 pm.

Last Updated December 1, 2022 3:38 pm.

In 1991, Toronto man Allen Chankowsky was diagnosed with Hodgkins Disease at the age of 21 — a blood-based cancer for which he received radiation therapy at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PMCC).

“That gave me 25 years of life and led me to have two beautiful children,” he tells CityNews.

However, he says that radiation therapy translated into a second cancer decades later, and he was diagnosed with salivary duct carcinoma in 2016.

“My cancer was diagnosed as being terminal, which means there was no cure. The best I could hope for was disease control for as long as possible,” he says.

With little research on his specific type of cancer, Chankowsky says treatment options were limited.

“Princess Margaret needed to be creative and find a way in which to attack my cancer. And that way was a treatment that is a mainstay treatment for prostate cancer patients. So my salivary gland cancer, which is a head and neck cancer, is being treated as a prostate cancer,” he explains. “That epitomizes creativity and the way Princess Margaret has used precision medicine in a creative context to help me.”

The concept of the creative use of science and its impact on research is highlighted in the foundation’s new awareness campaign, The Art of Conquering Cancer.

RELATED: Princess Margaret Hospital to launch campaign to personalize cancer treatment, report says

“True innovation and true net new discoveries – they don’t happen without creativity,” says Melanie Johnston, the chief marketing officer with the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation. “The Art of Conquering Cancer campaign is really meant to capture that idea that it takes both art and science to conquer cancer.”

Johnston cites a recent scientific breakthrough by PMCC senior scientist Dr. Ralph Da Costa as an example of the marriage between creative thinking and science that’s furthering new ways of battling cancer.

“One of our surgeons had a really great idea around a new innovation when he was shaving one morning. He was letting his mind run wild and that’s when the inspiration struck,” she says.

Da Costa invented a hand-held imaging device that surgeons can use to see cancer cells during cancer surgery, which would otherwise be invisible. The device is now entering phase-three clinical trials in breast cancer patients undergoing surgery. It is expected that the device could reduce the need for multiple follow-up operations and benefit patients around the world.

“When you think about medical research or cancer research, you tend to think about this very rigorous, strict scientific process. And it is that, but it’s that coupled with this more free-form creative thinking, and that’s really where the magic happens,” Johnston says.

Chankowsy says he is living proof of that magic, which helped him beat the grim statistics for salivary duct carcinoma.

“The statistics for my cancer dictate that 80 per cent of people would be dead within three years,” he says.

“So under the weight of that information, it was paralyzing and I did not believe I was going to live beyond the three-year mark.

“Not only did they take the scientific breakthroughs that were applied to other cancer types and apply it to me, they did it in a way that allowed me to live longer.”

Chankowsky says the “art of conquering cancer” helped him enjoy time with his family and see his kids grow up, who were only 12 and nine when he was diagnosed.

“It is allowing me to share the word that the creative application of scientific breakthroughs that the Princess Margaret is doing are extremely important,” he adds.

“The contribution and donations that people provide to support Princess Margaret are being paid forward. It’s helping people who have rare cancers, it’s helping people who have mainstream cancers, to live longer.

“When my life does come to an end, my goal is to die with my cancer, not from my cancer.”

Chankowsky says he promised himself that if he did live longer than the average expectancy of three years, he’d write a book detailing his experience and how to survive and thrive with cancer. That book is now published six years after his initial diagnosis.

“On the Other Side of Terminal is a book that serves to allow cancer patients and their families to realize that … there is another side to terminal, and it’s a side that’s full of love and life and opportunity,” he says.

“I wrote the book primarily to teach my kids that no matter what happens in life, that you don’t give up, that you continue to fight.

“I also wrote the book because I wanted to be that voice for rare cancer survivors. Rare cancer victims are people who have cancer that is not particularly well researched and they suffer the consequences of not having a lot of research.”

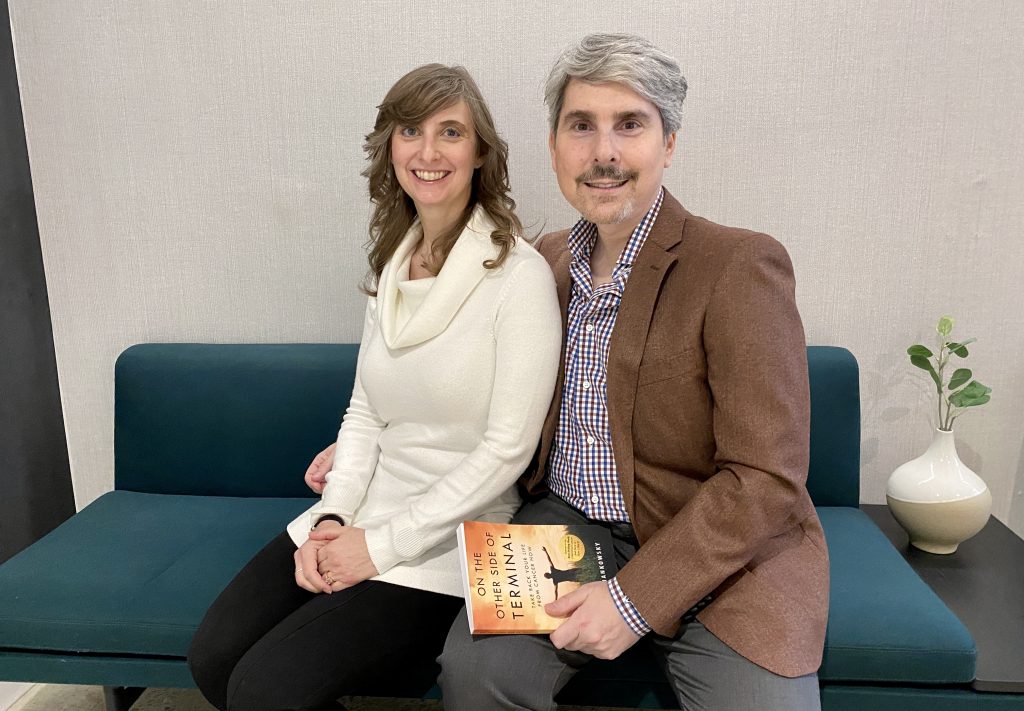

Allen Chankowsky and his partner Cynthia say it is important for patients to learn as much as they can about their cancer and advocate for themselves. CITYNEWS/Dilshad Burman.

Chankowsky says he wants to empower people with information and the understanding that the way precision medicine is applied to a particular person’s cancer is “exceptionally critical in longer life and disease management.”

In the book, he suggests that those diagnosed with cancer should try to learn as much about it as they can.

“Research your cancer, particularly now access to information is so easy that if you’re motivated enough you will be able to learn a lot about your cancer and be empowered to walk into your oncologist’s office with information that you could ask about,” he says. “You can be a more informed patient and that, in particular in my case, worked to create a better conversation around treatment approaches.

“People need to know that having cancer, particularly advanced cancer, is not a death sentence.”