‘Golden Age of homelessness’ is over, says one former homeless man

Posted April 14, 2023 11:19 am.

Last Updated May 25, 2023 2:17 pm.

Read this story on The Green Line

Editor’s note: Olivier prefers the word “homeless” over the term “unhoused” since he strongly identifies with the former term.

The “Golden Age of homelessness” is over, says one Toronto man who was chronically homeless for over a decade.

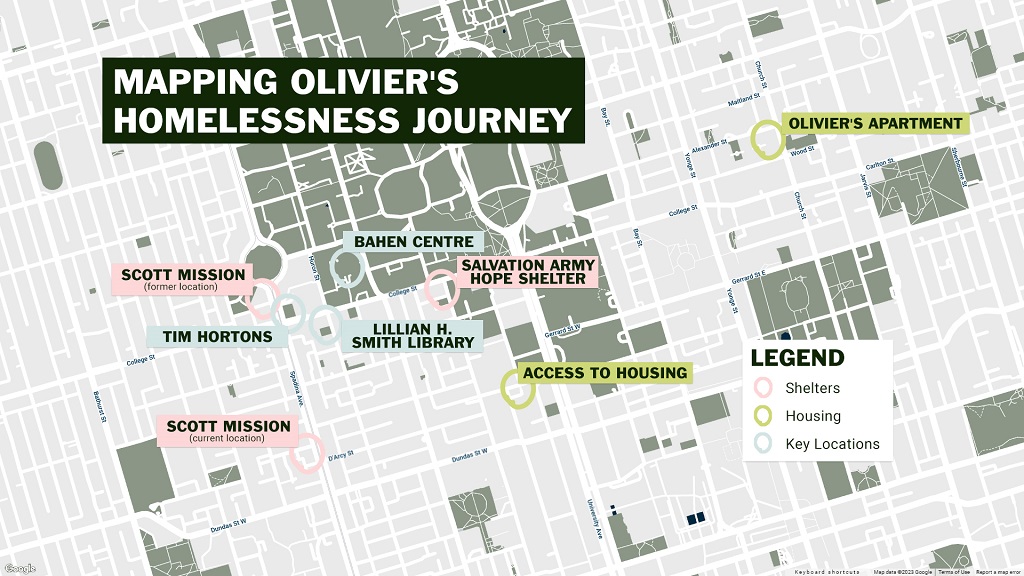

Olivier M., who preferred not to be identified by family name, first sought temporary shelter in Toronto 14 years ago. He says that from 2009 to 2013, it was easier to find help in the city, compared to today.

“I call it the ‘Golden Age of Homelessness in Toronto,’ because I could arrive through the Greyhound station at Bay and Dundas, and maybe sleep somewhere at a friend’s place or book into a backpacker’s hostel with whatever little dollars I [had],” Olivier explained. “The next day, I’m not worried. I came to the Salvation Army [Hope Shelter] here [at College Street and McCaul Street] and they got a bed for me. It was not a worry. There was no stress.”

As of late 2020, Olivier now lives in a bachelor apartment, thanks to a rent-geared-to-income subsidy from the City of Toronto. With it, 30 per cent of his monthly income goes to rent and the subsidy covers the rest.

Olivier M. stands across from 167 College St., the former location of the Salvation Army Hope Shelter until 2015. (Aloysius Wong/The Green Line)

But Olivier had to wait nearly a decade for it — which remains the average wait time to receive subsidized housing for an apartment like his, according to the City of Toronto’s website.

So until three years ago, Olivier — who prefers the word “homeless” over terms like “unhoused” because it’s the word he and other homeless people use with each other — did not have a permanent place to stay.

By 2019, Olivier says his experience of homelessness in Toronto and other cities had taken a turn for the worse.

The Salvation Army location he had previously stayed at had relocated, while the demand for shelter remained higher than ever. What’s more, he now had to call the City of Toronto’s Central Intake line to secure a bed, which is no longer guaranteed if you need a place to sleep that same night.

“Now you call them and they say, ‘No, we got nothing. Call again in one hour. Call again in one hour. Call again in an hour,’” Olivier recalled. “You get nothing the whole day. You try again the next day — nothing. Maybe on the third day you’ll get something. So definitely something has changed.”

It was around that time when Olivier began staying at Scott Mission, a Christian ministry hosting a men’s shelter in downtown Toronto, which was then located at 502 Spadina Ave. It has since moved to 346 Spadina Ave., with a new shelter space that operates 24 hours a day instead of nights only. But staff say that despite the increase in their shelter services, they remain at full capacity.

Jonathan Miller, chief ministry officer at Scott Mission, at the organization’s 24-hour shelter at 346 Spadina Ave. (Aloysius Wong/The Green Line)

“All 66 beds are filled every single night,” said Jonathan Miller, chief ministry officer at Scott Mission. “There is a huge demand in the city for emergency housing and for permanent housing. And we see that increasing more and more.”

Miller says that 64 per cent of their shelter residents are chronically homeless. These men, he says, have been homeless for six months or longer, with some whom they’ve served for over 12 years. Miller adds that they’ve been seeing more refugees and newcomers at their shelter, with 31 countries of origin represented among those they serve.

“Twenty-five per cent of our population in the shelter right now is from African countries,” said Miller. “They’re just trying to get those first steps of their journey here in Canada. But they need a place to start.”

Michael Hamilton, the manager of Scott Mission’s case management services, tells The Green Line that people’s stays at their shelter used to be more transitory.

“We had more movement within our shelter itself. Even though we were full, we were able to maintain waiting lists,” Hamilton said. “Now, people are reticent to move. They stay in place.”

Beyond Scott Mission, the entire Toronto shelter system often operates at capacity, with 72 people on average turned away from shelter each day in February. What’s more, Gord Tanner — the general manager of city hall’s shelter, support and housing administration division — recently warned city councillors that if a funding deficit of $317 million is not met by January 2024, more shelters will be shut down.

However, Hamilton adds that although people are staying longer since they’ve transitioned to a 24-hour model, their staff have been able to provide more services to the men in their care as a result. At their former location where they would only operate 12 to 14 hours a day, their clients would have to leave during the day before returning in the evening.

“So what you have then is a lot of the men leaving and riding the TTC all day or [sitting] in the shopping center,” he said. “They really have no place to go. They’re constantly being moved, and that really plays havoc [on] them. There’s no quiet spaces. So coming back [to the shelter] was sanctuary.”

Michael Hamilton, the case management manager of Scott Mission, in one of their offices where he and other staff conduct one-on-one meetings with their clients. (Aloysius Wong/The Green Line)

Despite this, Olivier, who also received support from other shelters like St. Felix Centre and the Out of the Cold program, said that he experienced moments where he needed a break from the shelter system.

“These services like Scott Mission — however cool they are or [however much] they make you feel welcome — they’re more there to give you resources, something to eat, clothes, wash your clothes, sleep warm, take a shower,” he said. “But [getting] at the root of that sense [of self-worth] that makes you almost, like, punish yourself, be homeless year after year … no one really tackles that from what I have seen. Not really.”

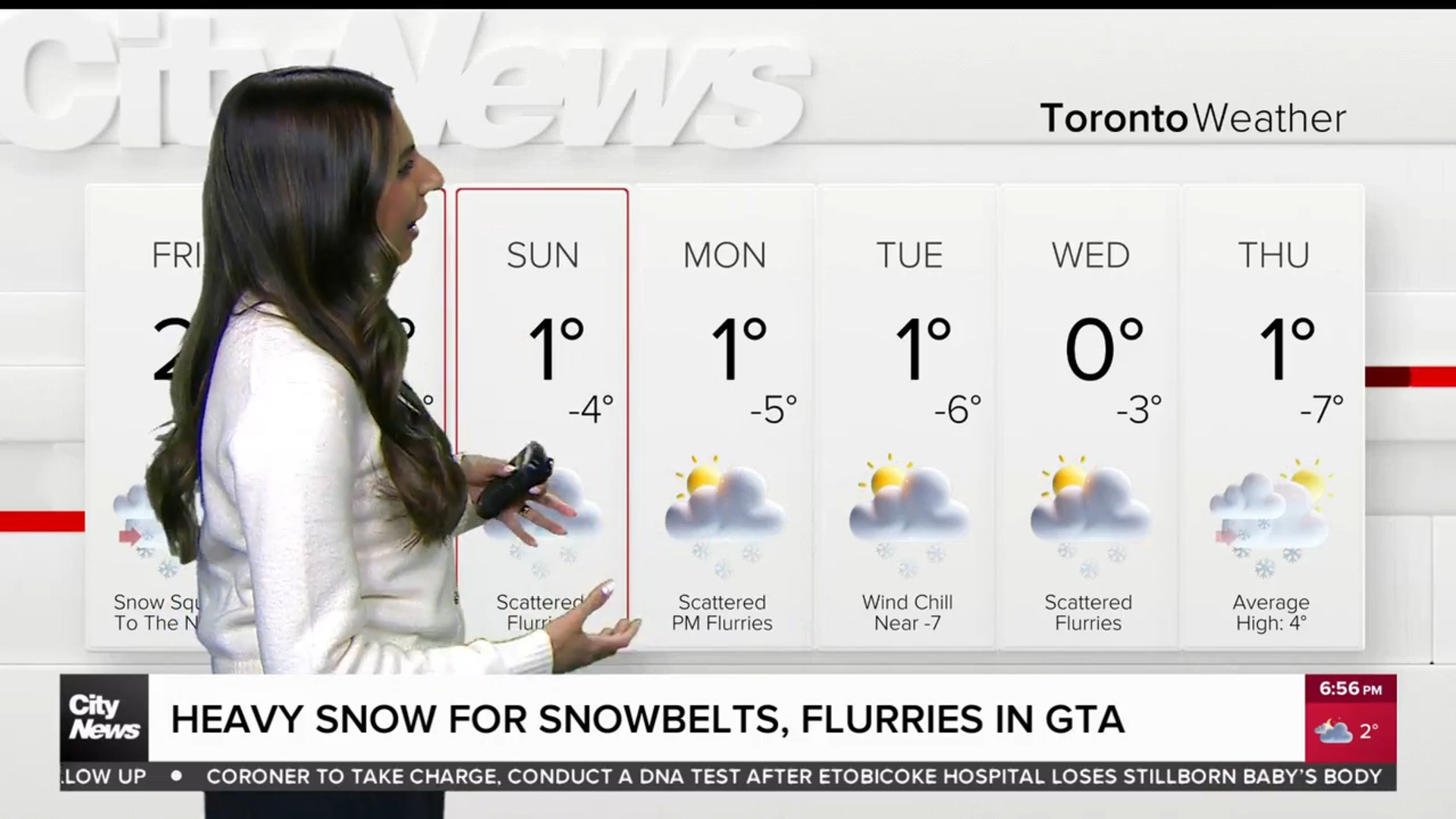

Olivier M. showed us several key locations in his journey from homelessness to permanent housing, including the City of Toronto Access to Housing building, past locations of shelters where he stayed, and places where he would spend time around broader society. (The Green Line)

So in the times when he wanted some distance from other homeless people, Olivier would go to places like the nearby public library or the University of Toronto’s Bahen Centre for Information Technology, which he described as a secret spot.

“It’s a spot I would come to, knowing that I’m not going to meet any homeless,” said Olivier, who would regularly spend his days at the Bahen Centre, and sometimes even sleep there with the help of one now-retired caretaker who welcomed him. “Coming here, I felt I had a chance to feel like a part of the general population.”

Being able to feel like a part of broader society is especially important when you’re homeless, he adds.

“You feel like a ghost. You feel disconnected from the general people that you see around you,” Olivier continued. “It’s almost like you feel … as if your dimension or your time-space continuum is a little bit out of phase with what you see around you. It’s there and it doesn’t leave you.”

He adds that what homeless people need most is a sense of connection and human dignity. “If you say a word to them, it could be worth much more than you think.”

Olivier M. sits outside the Lillian H. Smith library at 239 College St., where he frequently spent time when he was homeless. (Aloysius Wong/The Green Line)

Reflecting on his experience, Olivier says that the first step to solving homelessness is to give everyone a place to stay, whether that’s through subsidized or affordable housing programs. But ultimately, he says, homelessness is a “social illness” that requires healing.

“It’s a deep one that you cannot approach just with your head. Your soul and the heart [have] to be involved,” he said.

Miller agrees. “[Homelessness] is a complex issue,” he said. “In many cases, it’s not always the same factors that are in play. Every story is different.”

“There’s so much going on right now,” said Hamilton. “Sometimes we can forget that there’s still another strata that still needs that support.”

Today, with his subsidized apartment, Olivier has a stable place to sleep each night. But he still doesn’t feel at home.

“Even to this day, I call myself homeless, because there’s something in me that I need to work out and I haven’t found a way to work it out,” Olivier said. “For now, I have a shelter, a roof over my head, which is not nothing — it’s a lot. But I’m still waiting to get an actual home.”