Remains of 182 found near former residential school in B.C.

Posted June 30, 2021 10:12 am.

Last Updated June 30, 2021 11:19 pm.

Editor’s note: This article contains some disturbing details about experiences at residential schools in Canada and may be upsetting to some readers. For those in need of emotional support, the 24-hour Residential Schools Crisis Line is available at 1-866-925-4419.

CRANBROOK – More remains linked to the former residential school system have been found in B.C., this time at a site near Cranbrook.

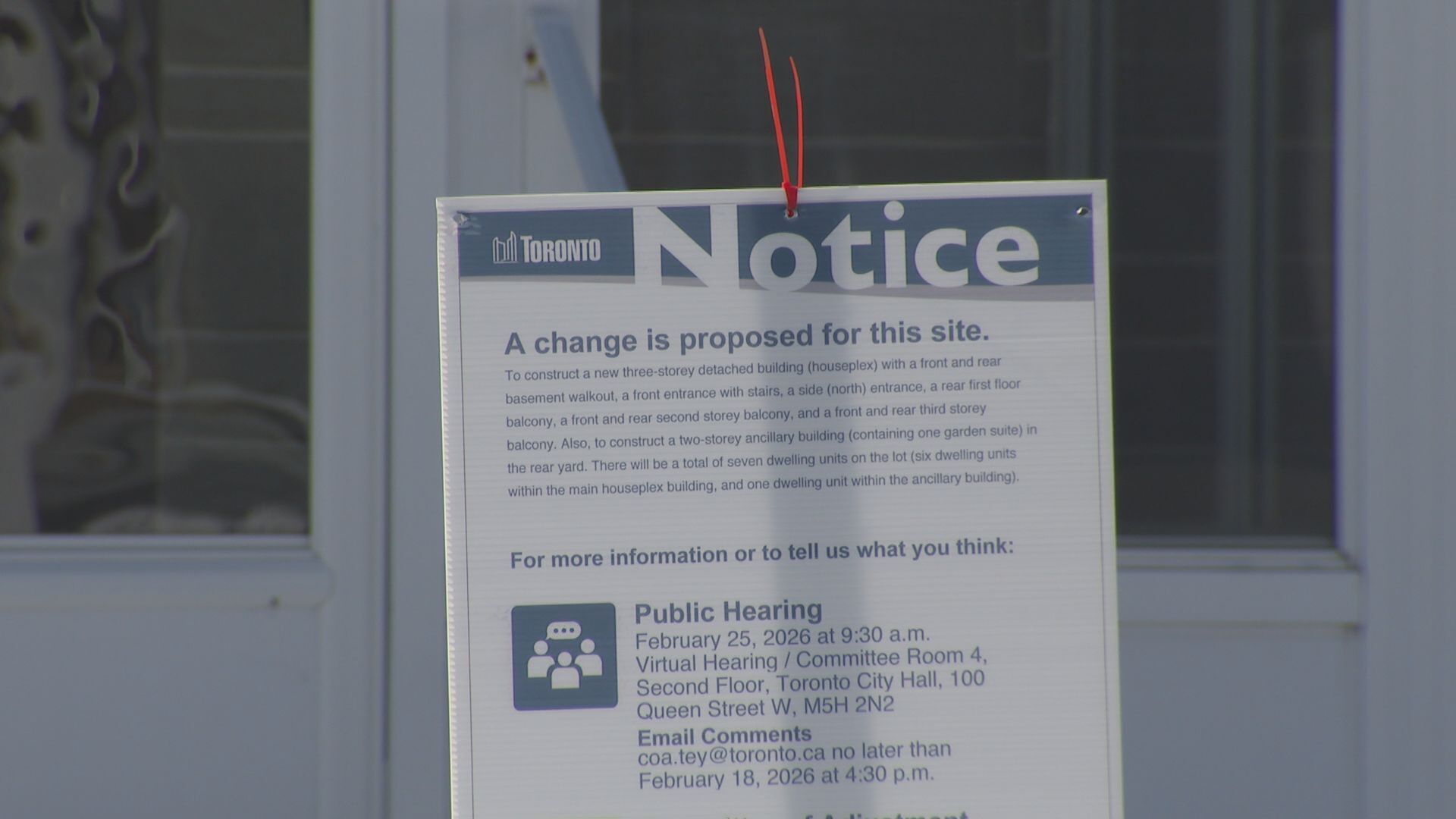

The Lower Kootenay Band says a search using ground-penetrating radar has found 182 human remains in unmarked graves.

In a news release, the band says the community of ʔaq̓ am began using the technology last year to search a site near the former St. Eugene’s Mission School, at the time known as the Kootenay Indian Residential School, which was operated by the Catholic Church from 1912 until the early 1970s.

Related articles:

-

Catholic group that ran B.C., Sask. residential schools to disclose records

-

Indigenous families of residential school survivors in B.C. continue to feel pain, trauma

-

‘We’ve just opened the door’: Reckoning with Canada’s history as 751 unmarked graves confirmed in Saskatchewan

It says the search found the remains in unmarked graves, some as shallow as 90 centimetres to 1.2 metres.

The Lower Kootenay Band says it’s believed the remains are those of people from the bands of the Ktunaxa Nation, which includes the Lower Kootenay Band, ʔaq̓ am and other neighbouring First Nation communities. The band notes it’s in the early stages of receiving information from the reports on what has been found, and it is asking for the public to respect its privacy.

This is the third large discovery of remains since May.

History of site ‘complex,’ work ongoing to determine if unmarked graves linked to residential school

In a later statement, ʔaq̓ am Nasuʔkin (Chief) Joe Pierre explained that the history of the area where the remains were found is complex.

“ʔaq̓ am Leadership would like to stress that although these findings are tragic, they are still undergoing analysis,” he writes.

“The community of ʔaq̓ am did not start to bury their ancestors in the cemetery until the late 1800’s. The St. Eugene Residential School, adjacent to the cemetery site, was in operation from 1912 to 1970 and was attended by hundreds of Ktunaxa children as well as children from neighboring nations and communities. Graves were traditionally marked with wooden crosses and this practice continues to this day in many Indigenous communities across Canada. Wooden crosses can deteriorate over time due to erosion or fire which can result in an unmarked grave. These factors, among others, make it extremely difficult to establish whether or not these unmarked

graves contain the remains of children who attended the St. Eugene Residential School.”

Discovery near Cranbrook follows those in Kamloops, Saskatchewan

Just last week, the Cowessess First Nation confirmed 751 unmarked graves were uncovered on the grounds of the former Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan. That discovery was the most significant to date in Canada.

That followed the discovery of 215 Indigenous children’s remains confirmed by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in Kamloops a month earlier. Some of the remains belonged to children as young as three years old. The search of the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, which was once the largest in Canada’s residential school system, renewed calls for all former sites to be searched across the country.

“Though we knew that many children never returned home, and their families were left without answers, this confirmation brings a particular heaviness to our hearts and our spirits all throughout Secwépemculecw,” said Kukpi7 Judy Wilson, Union of BC Indian Chiefs secretary-treasurer, after the search of the site in Kamloops in May.

Related video: Hundreds of unmarked graves found at former residential school in Saskatchewan

Pressure has grown in recent weeks after the discovery of remains for the Catholic Church to apologize for its role in the residential school system, which took Indigenous children from their families and communities, and forbade them from acknowledging their heritage and culture. They were forbidden from speaking their languages, and were punished when rules were broken.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued its final report on residential schools more than five years ago. The nearly 4,000-page account details the harsh mistreatment inflicted on Indigenous children at the institutions, where at least 3,200 children died amid abuse and neglect.

To date, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has identified the names or information of more than 4,100 children who died in the residential school system. However, the exact number remains unknown.

The United Nations is among those who have called on Canada to perform an exhaustive investigation into uncovering the remains of residential school children across the country.

On June 2, the federal government announced it was providing First Nations communities with funding to conduct such searches at former sites.

More work to be done in Canada

“We grieve [for] those youth not having the opportunity to enjoy life as you and I have,” said Howard E. Grant, executive director of the First Nations Summit, after the discovery near Cranbrook was announced on Wednesday. “I also grieve today for those who still survive the parents, the grandparents, the brothers and sisters, and their cousins who never had a chance to lovingly embrace their loved ones, but they still have them in their memories.”

Grant says he has mixed emotions.

“I’m happy to have found them. But at the same time, it brings back the traumatic memories that each one of us has embraced over the last 50 to 100 years. Each one of us needs further healing to adjust to all of these new found graves that are being identified at this time.”

He says Canada has “painted this magnanimous attitude” that it has taken steps to address the country’s shameful past.

“They apologize, [they say] they’ve done things to rectify. But if they would only look at the power of the Canadian government, the politicians and the social elite of this country, things have not changed. We talked about reconciliation, we talked about new relationship. That can only happen if and when action takes place with a sound work plan and implementation plan, and a desire and a commitment to make change which results in educating the populace of this country.”

"We look to the east and to the government and we point a finger. But we also point a finger to our backs, to Victoria. They too have a responsibility, because it is education that is the first step in this reconciliation." #bced #bcpoli #bcgov #fedgov

— Ria Renouf ???? (@riarenouf) June 30, 2021

Grant believes it’s important that new and young Canadians are educated about Canada’s true history

“It’s education. That is the first step in regards to this reconciliation. They need to be placed into the core curriculum of K to 12 and mandatory for at least the first two years of university for every individual Canadian to learn the history — the true history — of Canada,” he said.

Grant spoke Wednesday alongside the National Congress of Chinese Canadians (NCCC), which expressed its support for First Nations communities.

“The National Congress of Chinese Canadians stands with our First Nations friends in remembrance of the tragic loss of the loved ones, especially of the missing women and children and their unknown depths in great numbers,” said David Choi, national executive chair of the NCCC.

Grant wants to say thank you to the Asian colleagues and people who have "stood with First Nations for the past few months."

— Ria Renouf ???? (@riarenouf) June 30, 2021

“This is a nationally sad and challenging time in Canada, in Canadian history. When Chinese were severely indiscriminately discriminated against, it was our First Nations friends who treated us as equals, offers warmth and comfort. And in kindness with compassion and friendship,” he added.

This is difficult to accept but necessary

Carey Newman, an Indigenous artist and University of Victoria professor, says over the past month, his reaction has been slightly muted since he’s heard about these unmarked graves “for as long as I can remember.”

“There’s a bit of catharsis in the confirmation of survivors, in the confirmation of what people have already told us,” he says.

However, hearing Canadians say they are surprised by the news, Newman says it was a bit “upsetting because I knew about it and because we’ve been told about it over and over.”

“But I think it’s the human response to having something that you believe for so long, be proven different to what you believed. That can be a difficult thing to come to terms with,” he adds.

“I know so many people in this country who have grown up being taught and believing the narrative of the progressive, welcoming, polite Canada. And this is a direct contradiction to that.”

While Newman believes the recent findings will not discount the Canada many people have come to for a better life for, it’s important to remember “the genocide that exists within those colonial ways.”

Newman adds it’s about time Canada awakens to the extent of historic and ongoing treatment of Indigenous people in the country, saying the acknowledgement of these lived experiences is a step in the right direction.”[It’s time] to make our colonial history part of the fabric of our national identity, where the humble exceptionalism that we promote of ourselves, to each other and the rest of the world includes the terrible things that this country was built on,” he says.

“Once it is no longer this continued fight to convince people that residential schools were not well-intentioned, that they were places where culture was stolen, where lives were lost, where communities were broken, then we’re getting to the truth part. And once we have that, then we can move on to reconciliation.”

However slow the country makes steps towards acknowledging Indigenous experiences, Newman says he is an optimist.

“I’ve seen change. I’m the son of a residential school survivor. And what that means is, I can see in the difference between my father’s life and me and my sisters’ lives, is a pretty substantial difference. So incremental change happens,” he says.

“I’m Not saying that it’s been fast enough, because we still fight for recognition, we fight to be seen, we push back against the systemic racism that has so many Indigenous people in jails, so many Indigenous children being taken from their homes into social care. So I think that this represents another step.”