Inside St. James Town’s game-changing food system: how residents are feeding themselves

Posted January 26, 2024 3:06 pm.

Last Updated January 26, 2024 7:35 pm.

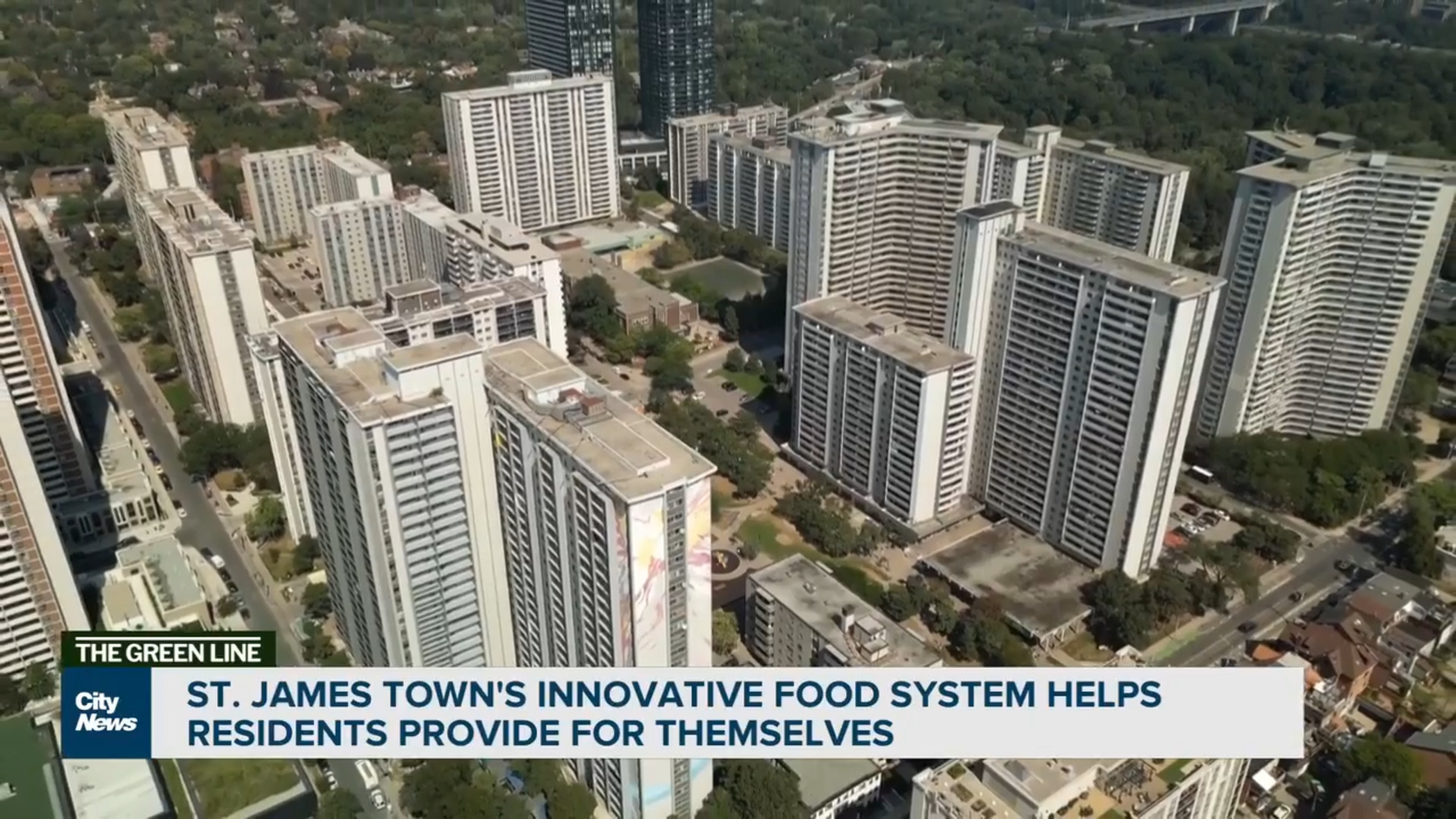

St. James Town, a culturally diverse neighbourhood just north of Cabbagetown, is popularly known as “a world within a block.”

More than 20,000 residents live within roughly half a square kilometre. But such a dense population can result in a lack of food and rising hunger.

Sarah Buchanan, campaigns director for the Toronto Environmental Alliance, tells The Green Line that neighbourhoods like St. James Town can experience the worst effects of climate change, leading to food insecurity.

“When climate emergencies happen — for example, heat waves or floods — those can cause things like power outages that can cause a lot of instability and it can cause people to need a lot of support,” Buchanan explains.

“One of those ways that it can cause destruction is in people’s food system, just straight-up access to food, where we get our food. It can mean that it’s harder to get to the places where we access food, or it’s harder for food to get to the shelves to feed the many people who live in this neighbourhood.”

That’s what happened during the massive Northeast blackout of 2003 — the most widespread blackout in North American history — which affected much of the eastern seaboard. Some people were stuck in high-rise buildings with no access to food or power.

In response, one group of residents in St. James Town decided to build a climate-conscious food system so they could provide for themselves in case something similar happened.

The OASIS Food Hub is run by residents from the St. James Town Community Co-Op. They do everything from handing out food through its Good Food Buying Club to producing their food through micro-farms.

Josephine Grey, president and co-founder of the Co-op says her goal is to ensure there’s onsite capacity to design, build and sustain the neighbourhood’s own food hubs.

“When this whole thing began, [it] was how do we help improve access to healthy food for newcomers? And we started realizing more and more, well, the whole food system is a mess,” Grey explains.

“One of the best ways to solve the ecological crises and climate crises we’re facing is to fix our food system. So if we can, in this community, demonstrate a variety of ways that even in a high-rise urban concrete jungle, we are able to be biodynamic, to grow healthy, sustainable food — and we’re able to do it in such a way that benefits all the residents and the whole community by having them be involved in it directly.”

Since the hub launched in 2019, it’s helped 600 households, according to Grey.

As of December 2023, the St. James Town Community Co-op received an investment of $1,000,000 over three years from the Northpine Foundation, so it can tackle local food insecurity.

With this investment, the Co-op is looking to improve the OASIS model through community engagement. For example, residents like architecture professor Richa Narvekar brought in student designs to revitalize an unused swimming pool into an aquaponics centre.

“St. James Town has this vibe around it, which is very derelict as if this is where everything comes to lose hope. And a project like the Food Hub brings hope. It’s something that’s desperately missing,” Narvekar says. “I think it’s not really that hard, given any kind of background or understanding of urban design or urban history, to imagine even this place becoming vital and beautiful and a source of food for the neighbourhoods that surround it, as well.”

However, limitations like zoning regulations that prevent growing food in residential areas are setting the hub back. But Grey is hopeful about building a sustainable food model that can be replicated in neighbourhoods across Toronto.

“I have to confess: There’s no way we’re going to be making a lot of profit from making healthy, affordable food available to low-income people. We can, however, become self-reliant and self-sustaining,” Grey says.

“If we look at a triple bottom line, and if we are to understand that being able to cover our operations being a non-profit doesn’t mean being unsuccessful — it means being successful at what we’re trying to achieve, and that may not look like what a food corporation is trying to achieve. And I don’t care because that’s not helping us. What we’re trying to do is already helping a lot of people.”