New Indigenous-led guide helps First Nations track local wildlife with camera traps

Posted September 8, 2024 5:27 pm.

Last Updated September 8, 2024 5:29 pm.

Terry Jones’ Elders always knew wild cats roamed across Magnetawan First Nation lands off the shores of Waaseyaagami-wiikwed (Georgian Bay) in northern “Ontario.”

But the province’s Ministry of Natural Resources wouldn’t acknowledge them due to “lack of documentation,” according to the species-at-risk and research technician with the community roughly 80 kilometres south of “Sudbury.”

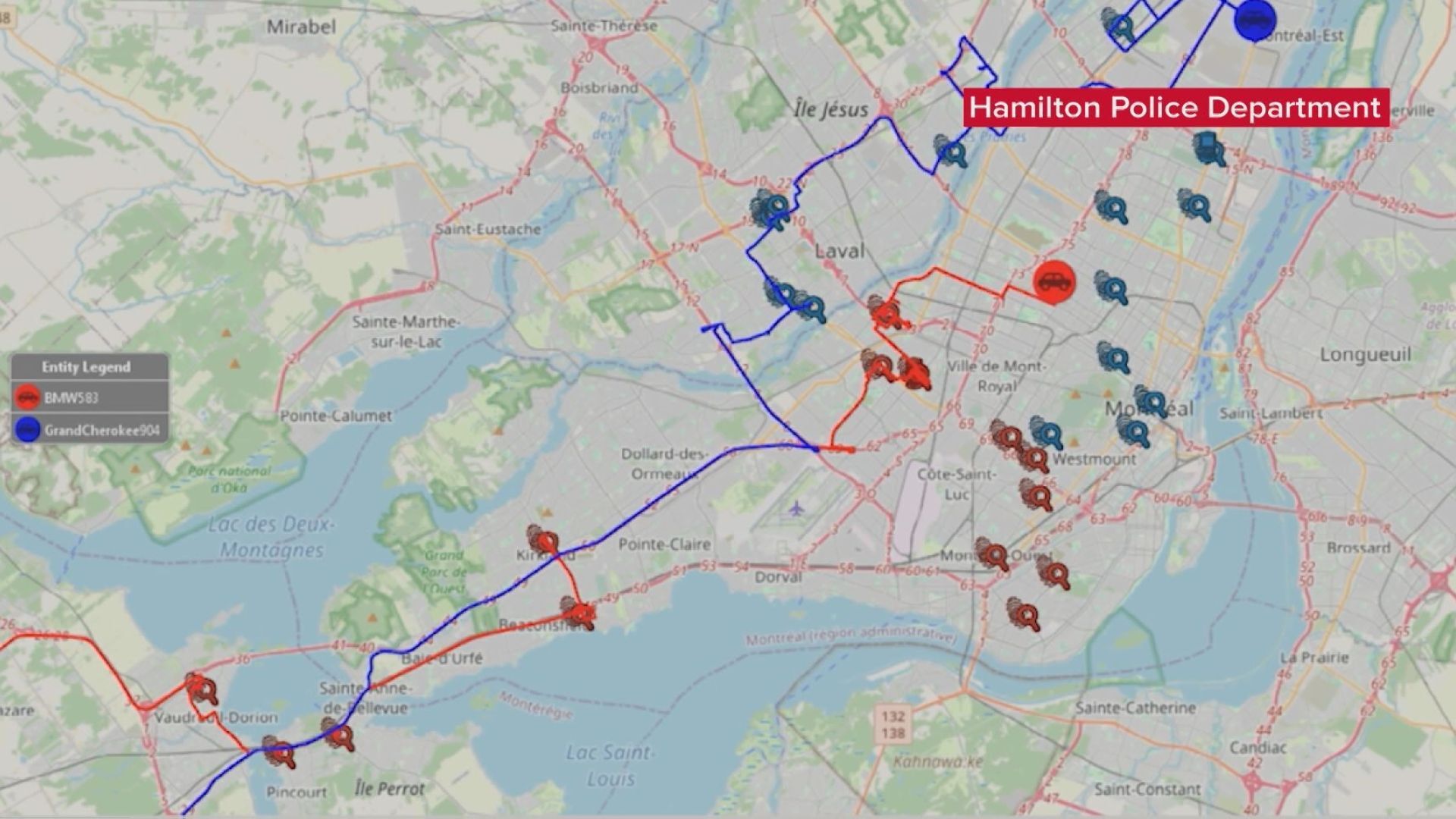

So when wildlife camera traps captured a photograph of a bizhiw (lynx) last spring, and again several months later, Jones and his community felt validated.

The camera traps had been set up on the nation’s territories to photograph medium-to-large mammals — particularly moozoog (moose) — after Elders and other community members expressed concern about their populations.

Youth hunting on their territories had reported the large mammals weren’t found in areas the Elders had expected them.

Moozoog populations have been rapidly dropping across Anishinaabek territory, according to a 2022 study by the Anishnabe Moose Committee, which concluded the species’ decline can be partly attributed to a mix of sport hunting, logging and climate change.

“We’d go out and see very little presence, or just nothing there at all,” Jones told IndigiNews. He wondered why the mammals were disappearing, how they were actually using the land, and at what times of the year.

According to provincial data, there are an estimated 404 moozoog in the Wildlife Management Unit that includes Magnetawan — a number predicted to decline 13 per cent by 2030.

Two decades ago, provincial researchers concluded the region hosted at least 550 of the massive ungulates, which gradually fell over subsequent years.

The First Nation has long been well-versed in species-at-risk monitoring, with long-standing programs to monitor miskwaadesiwag (turtles) and ginebigoog (snakes) in its territory, which Elders had noticed were being frequently run over by vehicles on two local highways.

But to start protecting other important species on their lands, Magnetawan leaders realized they first needed to grow the community’s monitoring capacity.

So the First Nation teamed up with University of Guelph ecologist Jesse Popp, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Environmental Science who holds a PhD in Boreal Ecology and is a member of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory.

She became quickly interested in supporting the First Nation’s efforts to monitor and restore biodiversity on its lands.

A makwa (bear) looks up-close into a camera trap placed on Magnetawan territory, part of the First Nation’s wildlife monitoring program. Photo courtesy of MAG.

Magnetawan pitched the idea of setting up camera traps — a relatively easy and less-intrusive way of counting species compared to physical tracking, which can leave a human scent trail that risks scaring mammals from an area.

Despite the time needed to set up the cameras — installing them can leave a person’s scent for a day or two — the devices are themselves scent-free, relatively affordable, and can be left to collect footage for between six to 12 months.

Now, the northern “Ontario”-based research project has joined forces with the University of Calgary as well as several communities in northern “Manitoba,” including Opaskwayak Cree Nation, which has also seen its moose numbers decline.

Together, they’ve formed a Moose Alliance to tackle the problem across provincial lines.

On Aug. 26, another “Manitoba” community, Pimicikamak Cree Nation, applied for a court injunction calling for the cancellation of all moose sport-hunting licenses on their territories due to the population crisis.

“Our nation advocates for stronger treaty, contractual, and environmental protections to ensure community engagement in moose hunting,” Pimicikamak Cree Nation Chief David Monias said in a statement.

“We believe in habitat restoration and in sustainable hunting practices reflecting our customary laws of the duty of stewardship.”

At Magnetawan First Nation, two graduate student scientists started working with Nadine Perron — a conservation biologist and wildlife specialist on the First Nation’s species-at-risk team — to help set up their camera traps.

One of the students, Claire Kemp, recalled how the community expressed the most concern about moozoog, but also hoped to capture as wide a variety of medium-to-large mammals as possible.

One of the students, Claire Kemp, said the community expressed the most concern about moozoog, while also hoping to capture as much of the range of medium-to-large mammals as possible.

“We had to work out what the methods would be based on what the community wanted,” Kemp explained.

She and fellow graduate researcher Kate Yarchuk decided to place their cameras near two highways, 69 and 529, and a set of railway tracks, chosen because such “linear features” often have negative impacts on wildlife.

But working out some details of the cameras — such as how many to deploy, how far apart to mount them, and how to standardize their images — was more challenging than they expected, Kemp said.

After drowning in research papers recommending various camera installation methods, they decided to create an easy-to-follow, step-by-step guide for other communities hoping to monitor local wildlife using the technology.

“Neither of us were really interested in publishing papers,” said Kemp, “but if we could create a resource that’s useful to communities, that’s something we care about.”

In theory, any community interested in wildlife monitoring could use their guide, which was reviewed by Magnetawan First Nation, the province and Popp at the University of Guelph.

But Kemp said the resource they wrote is especially aimed at communities hoping to monitor large- and medium-size mammals.

Kemp said the guide “almost walks you through the way we decided to do everything, and why,” addressing issues her team faced, including how many cameras to place where, and whether cameras are in fact the best tool for a community’s wildlife goals.

Armed with nearly three years of camera data, Jones concluded larger mammals like moozoog and waawaashkeshiwag (deer) tend to avoid traveling close to highways — unlike miskwaadesiwag (turtles) and ginebigoog (snakes) — likely because of noise.

But the larger ungulates do use local railway tracks, the study found, because they offer easier passage between areas.

“Our predators, like wolves, are using the train tracks to hunt,” Jones said.

A ma’iingan (wolf) captured on Magnetawan territory using camera traps as part of the First Nation’s wildlife monitoring program. Photo courtesy of MAG.

Yet unlike many highways, railways typically have few accommodations to protect wildlife.

“Railways are not doing anything,” Kemp said. “And it’s an issue because they’re everywhere.

“Something that community members really want is for this research to show that this is an issue, and that (railway companies) have to do something about it.”

Kemp has discussed that problem with community members, based on their generations of knowledge — she’s been asking what kinds of wildlife protections they’d like to see near train tracks.

Proposals include fencing, a lighting system, or warning sounds to scare animals off the tracks.

“But then you have to weigh up noise pollution and light pollution,” Kemp noted, “and what is the lesser evil of all of these things?”

A new highway is also slated to be built through the Magnetawan No. 1 reserve, and Jones hopes to use the camera trap data and community feedback to help determine what wildlife mitigation measures will be needed for the new road.

Additionally, Magnetawan First Nation is also planning to add an audio-recording element to its research, Jones said, thanks to a doctoral student who wants to install microphones along local highways and railways, to investigate the impacts of noise on wildlife.

Jones said his community’s hope is to gather as much information as possible — and to work with youth and Elders to better understand the challenges faced by their moozoog relatives.

“We want to make sure that our future generations still have the knowledge and capability to go out and harvest the moose whenever they feel like it,” he said.