What causes lake effect snow squalls?

Posted December 23, 2019 10:21 am.

Last Updated February 4, 2020 5:03 pm.

Lake effect snow, also known as lake effect snow squalls, isn’t really something that I had ever dealt with before moving to the Great Lakes region, and there aren’t many places in the world that have the right ingredients to make it happen. So what exactly do you need to get these massive dumps of snow to happen?

To put it simply, if cold air moves over top of a warmer large body of water and the winds are strong enough, but not too strong, we could get lake effect snow.

Where are the snow belt regions?

If you have caught one of my forecasts during the winter months, you have probably heard me mention the snow belt regions, but where exactly are the snow belts here in Ontario?

Often times I am referring to the areas that are downwind of the lake when the wind is blowing out of the north or northwest.

In southern Ontario, we are typically referring to Grey, Bruce, Huron, Perth, Middlesex, Wellington and Dufferin Counties, as well as London, Barrie, Midland,Orillia, Innisfil and the north portions of York and Durham Regions.

When the wind is west or southwest, we are looking at very different regions, but I don’t consider them exactly as the snowbelt regions.

Take a look at who would typically see lake effect if the conditions were prime for it with each wind direction:

How does it work?

It is actually a pretty complex scientific explanation, but I am going to do my best of boil it down, so for the weather geeks out there, don’t @ me if I am not giving the full explanation of the latent heat of condensation aiding in convection and positive buoyancy. So here we go:

Body of water

First, you need a body of water that is large enough and warm enough to produce enough evaporation to provide the fuel for cloud development and eventually, precipitation. Typically the longer the distance the wind is traveling over the lake, the more moisture it is going to pick up and the more precipitation you could potentially see.

This measurement of distance is referred to as fetch. No, not that fetch.

Typically, a lake will need the air to have at least 35 km/hr winds to pick up enough steam (literal use of the word steam here) to produce a snow squall band.

Ideally you will want to see a fetch of roughly 100 km, to pick up enough heat and enough moisture to produce heavy snow. There has been a few occasions where smaller bodies of water, like Lake Simcoe have had a few streamers trail off of it, but it was the other component making up for the shorter fetch.

Water Temperature

Lake temperature will play a part in this too, but it is not as important as the air temperature and the relationship between the two of them.

Early in the season when lakes are still pretty warm from the summer, we can see some lake effect snow and even lake effect rain, but when we start hitting the mid-winter months, any of the unfrozen parts are lake are going to running between 0 degrees and 2 degrees, so you will need even colder air in January than you would need in March.

Air Temperature

That brings us to air temperatures.

In order for lake effect snow to get going, you are looking for at least 13 C temperature difference from the surface of the water to roughly 1,500 metres above where it is constantly cooling with height. The air right at the surface will become very similar to lake temperature as the lake is evaporating, and since it is warmer it will start to lift and create convection.

As this warmer and moister air starts to lift, it cools and condenses into clouds. When the air becomes saturated and can’t hold any more water vapour, you start to get precipitation and since it is so cold, it comes in the form of snow typically.

Wind & Wind Direction

As Queen says in Bohemian Rhapsody, “any way the wind blows doesn’t really matter to me,” but it does to lake effect. That is the driving force behind who gets the snow and how far inland it is going to be carried.

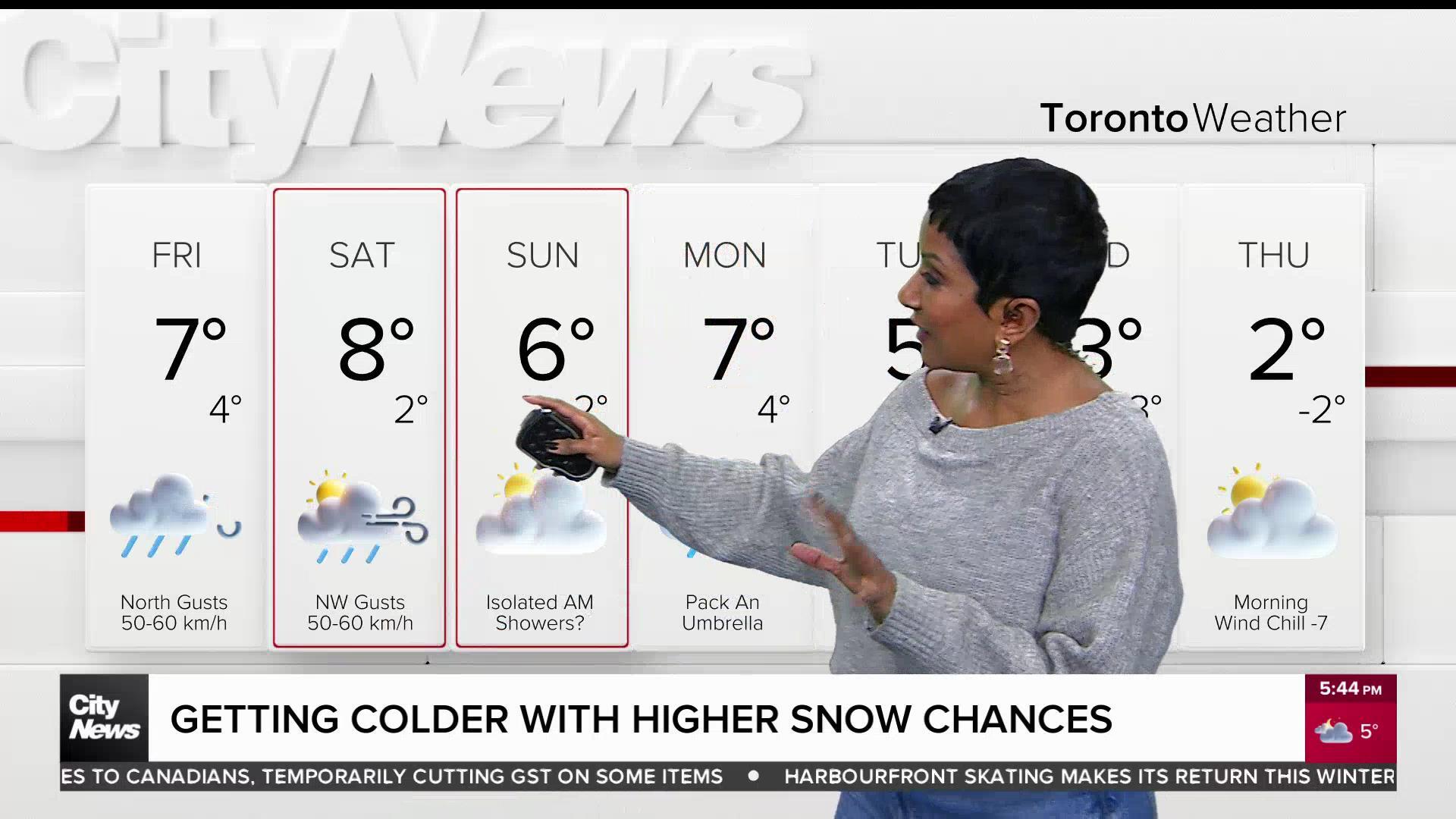

Typically you will need to have wind speeds in the range of 20 to 60 km/hr to find significant bands of lake effect, and anything over 60 km/h might be too strong to effectively carry that lake moisture inland, since there will be too much mixing of the air happening in the lower atmosphere.

Ice Coverage

When the lakes freeze up, it is basically like shutting off the taps.

When you get the surface of the lake mostly covered in ice, the air isn’t picking up enough moisture to generate the squalls.

Typically, Lake Erie is the first to freeze, and when that happens, the folks in the Buffalo and the southern Niagara region breathe a little easier, but the snow making guns at Blue Mountain are working harder when it happens to Georgian Bay.

Recent Examples

Just recently, we had a few significant band of lake effect snow hammer Buffalo and the southern Niagara Region with snowfall rates of 2-4 cm of snow per hour. That is a crazy amount to come down in such a short amount of time. That bands itself was only about 20 km-wide, so a drive of about 15 minutes would make it seem like a totally different planet; clear and sunny one minute and whiteout conditions the next.

Southern Ontario has seem some fairly major lake effect snow outbreaks in recent years, including one in London in 2010 that left 144 centimetres of snow on the ground. That same outbreak of cold air left hundreds stranded on Hwy 402 near the Canadian-US border.