Land before dinosaurs: Fossils from Permian era exposed in P.E.I. after Fiona storm

Posted January 31, 2024 1:54 pm.

Last Updated January 31, 2024 2:45 pm.

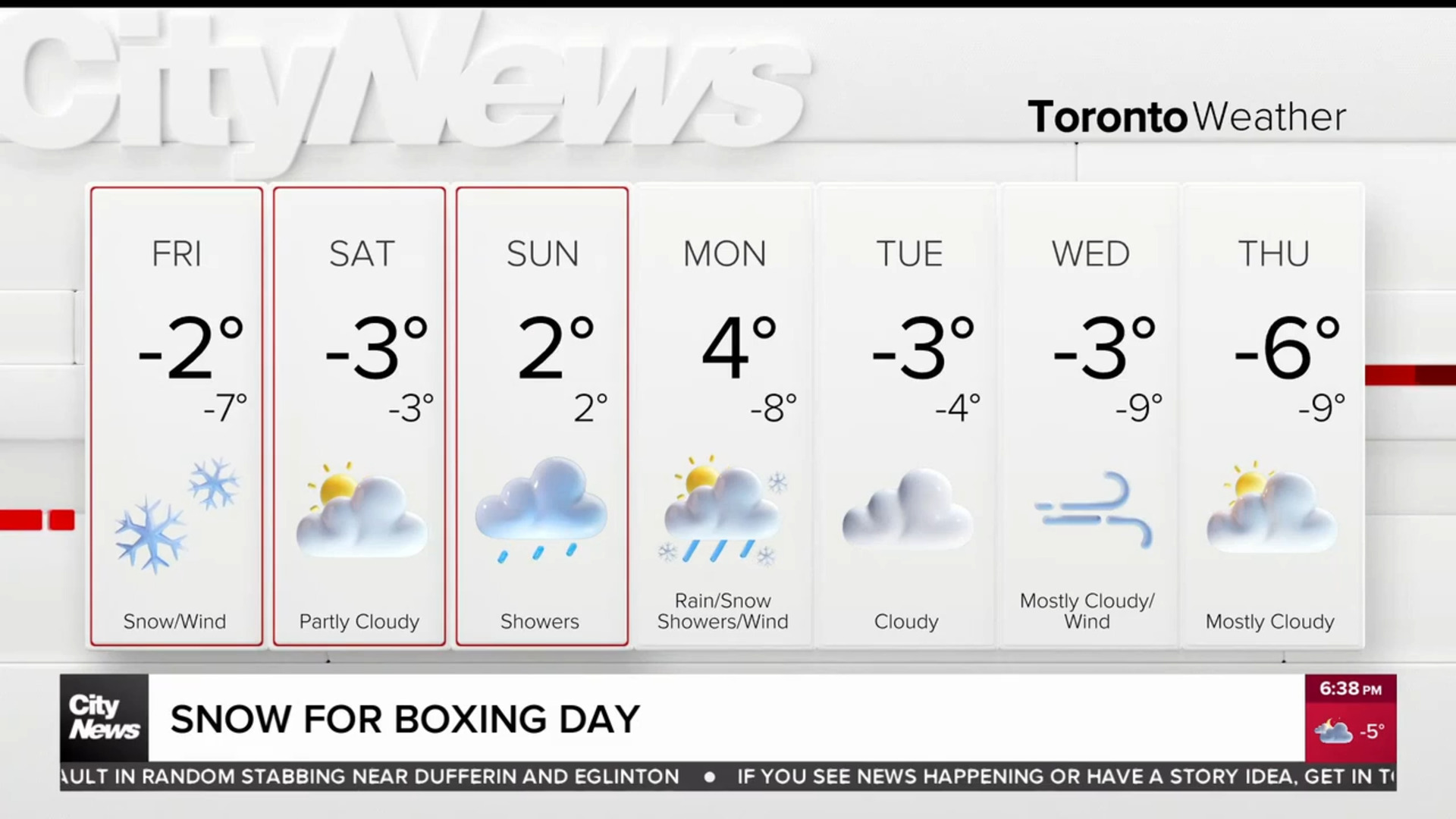

Post-tropical storm Fiona has revealed traces of a time before dinosaurs, preserved in the rock and sandstone of Prince Edward Island and exposed in the tempest’s wake.

In September 2022, the power of the waves from Fiona’s hurricane-force winds caused coastal erosion, breaking apart cliffs, washing away dunes and revealing hidden fossils, says John Calder, a Halifax-based geologist and paleontologist.

Calder said Fiona, “took away and it also gave.”

“I don’t mean to suggest that erosion is a good thing but as far as paleontology goes, it really is the main reason why discoveries continue to be made,” said Calder, who works for the Prince Edward Island government as a consultant.

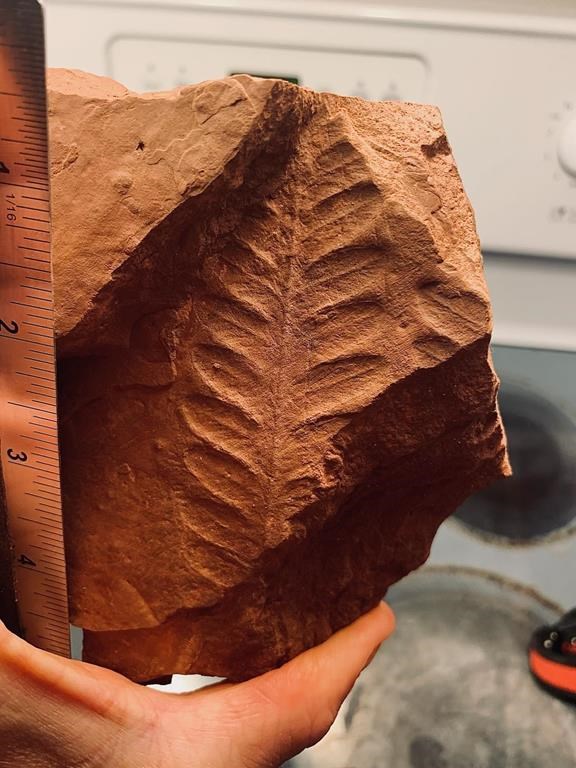

Fossils discovered after Fiona ripped through the Island include a front and hind footprint of a dog-sized tetrapod — animals on the evolutionary tree of life between amphibians and reptiles — an extinct seed fern, a wing of a dragonfly, and a tiny trackway, which is a path trodden by creatures.

The fossils uncovered by Fiona are from the Permian period — between 300 million and 250 million years ago — and about 70 million years before dinosaurs walked the Earth. During that period of history the planet was going through an “incredible time of global warming,” and Prince Edward Island was a tropical place, Calder said.

“A vast area of lowlands that were traversed by seasonally flowing rivers, it was tropical, yes. But it was not yet an island. This was the kind of environment where we had seasonal rivers, seasonal floods, in a tropical environment with a tropical sun beating down.”

Also found in the red rocks is evidence of some of the other creatures that called P.E.I. home such as “very fearsome, large reptiles and small scampering little lizard-like ones.” Calder also said an array of creatures from crawling invertebrates — worms and millipedes — to dragonflies are preserved as well.

Patrick Brunet, a resident of North Rustico and an amateur fossil hunter, helped Calder search for the fossils. In an interview, Brunet said he “loves” fossil hunting on the Island and is collaborating with Calder and Parks Canada.

Fossils help him connect to wonder, nature and existence itself, he said.

“I enjoy feeling small in the hugeness of time.”

A “P.E.I. State of the Coast” report published last year by the University of Prince Edward Island analyzed the erosion caused by Fiona, whose winds caused major damage across the Atlantic region. The coastline eroded rapidly during the storm because of the ferocity of waves, the report said.

The post-tropical storm washed away blocks of sandstone from the North Shore, showcasing Fiona’s power, Calder said. Those blocks had their share of fossils, but the storm “cleaned off the cliffs in a way that we hadn’t seen in our lifetime,” he said.

“It exposed a great deal of rock surfaces that we had never seen before and, of course, there were an awful lot of fossils exposed after Fiona as well. So it both took away and it revealed new fossils. I would say reveal more than it took away.”

Calder said the government is looking to set up a research facility on the Island where such discoveries can be stored and studied.

Prince Edward Island is one of three significant places in the world where fossils of footprints from the early Permian period are found, he said. The other two are in New Mexico, in the United States, and in Germany.

“This is the only place in Canada, only place in all of the huge, huge land mass of Canada, where rocks of this time period are found, representing the record of life on land,” he said.

In the Permian period, the kind of trees that grew on P.E.I. resembled the Norfolk Island pine, which is sold in grocery stores in December as a potted Christmas tree, Calder said. “Also towering tree ferns.”

The foliage of the tropical trees and ferns is preserved in the rocks, he said.

Footprints in P.E.I. were created when animals walked on a mixture of water and sand or mud right before it hardened into rock.

Calder compared it with footprints left behind by a cat or bird on recently poured cement sidewalk.

“I would love to be able to — just for a moment — see all of this in its splendour,” Calder said. “But the best we can do is we can reconstruct it from the fossils and imagine what it was like.”