Ontario judge declares mistrial over F-bomb controversy

Posted February 3, 2017 3:53 pm.

Last Updated February 3, 2017 4:22 pm.

This article is more than 5 years old.

An Ontario Superior Court judge has declared a mistrial in a drug case he was presiding over, after being accused of cursing as the defence was giving his closing arguments to the jury.

Justice Robert Clark was confronted with the allegations he used the F-word before the jury was to begin deliberating in a Toronto court.

Transcripts of the courtroom discussion reveal the judge’s initial disbelief.

Judge: I, I, I can tell you that I am astounded. If it was heard, I guess I said it. But I, if I said it, I can tell you, it was entirely meant for myself. I don’t usually speak aloud. I suppose from time to time I might utter something under my breath when something happens, but, uh, if, if I said that, I was utterly unaware of saying it and I certainly didn’t intend for anyone to hear. This takes me utterly by surprise.

Clark then asked the Crown prosecutor if he heard the expletive.

Crown: I did. My impression was that it was something muttered under your breath. And I only heard it because I happened to be looking at your face at the time.

Judge: If I said it, and I don’t think that I did, it was completely unintentional and I apologize profusely. It’s utterly inappropriate obviously.

The audio was then played repeatedly in the court, without the jury present and Clark concluded that he could not hear definitively whether he said the offending word.

Judge: I can’t hear it. I simply can’t hear it. I am clearing my throat a couple of times, granted I am making some noise, but I don’t hear myself saying that.

Defence: Audiotapes don’t capture everything that is said in court. My client heard it. The Crown heard it. The court reporter is prepared to certify that’s what was said. You represent the administration of justice. Everything you say, everything you do, has great sway over a jury.

Clark, while not admitting to using the word in front of the jury, declared a mistrial the following day.

Judge: I am not convinced I said what is attributed to me. Given the almost inaudible recording, I am not persuaded that the jury heard me utter anything. But, given the importance of there being no blemish on the integrity of the trial, I am going to declare a mistrial.

The accused in the drug case later went on to plead guilty in front of a new judge.

This is not the first time Clark has been faced with a mistrial because of concerns about his behavior — a situation almost unthinkable in legal circles.

In 2010, he tossed out a sensational murder conspiracy case involving a dominatrix and an alleged hitman, after agreeing his facial expressions from the bench portrayed a “reasonable apprehension” that he had a bias for the Crown’s case.

And in 2015, similar allegations were levelled against the judge in the high-profile murder case of Adib Ibrahim, a taxi driver facing a second-degree murder charge in the death of skateboarder.

The Defence submitted a mistrial application on the grounds the judge was “consistently and persistently seen shaking his head, appearing to display annoyance and disapproval of the Defence.”

The judge refused to declare a mistrial, explaining his behavior by saying he has a “stentorian voice,” but acknowledging that “when my face is in repose, I have what could fairly be described as a stern visage.”

Ibrahim was convicted of manslaughter and is appealing his conviction.

Defence lawyer David Butt, who has written publicly about the need to do a better job of “judging the judges,” said a judge declaring two mistrials because of his alleged behavior is likely unprecedented.

“Once is extremely rare; two is virtually unheard of,” he said. “It’s important that these events be looked at very closely.”

Related stories:

Judging the judges: Ontario justices faced with misconduct allegations

Judge who wore ‘Make America Great Again’ hat in court no longer hearing cases

Accused in ‘knees together’ sex assault retrial acquitted

Convicted murderer wants new trial because judge dismissed disabled juror

Clark “respectively declined” comment, but in an email to CityNews, his assistant said she “would strongly urge you to listen, yourself, to the recording of the proceeding. That way you can determine, for yourself, whether Justice Clark actually said the word attributed to him.”

CityNews has listened to the recordings and, because of poor quality, is unable to determine whether there was swearing from the bench.

Butt has publicly chastised the process of “judging the judges” as being too secretive and slow to change.

“Judges have a lot of power,” he said. “They can affect the liberty of every citizen. In every sector we have seen oversight expand and grow with the times. It has simply not happened in the judicial sphere and it is long overdue that they catch up.”

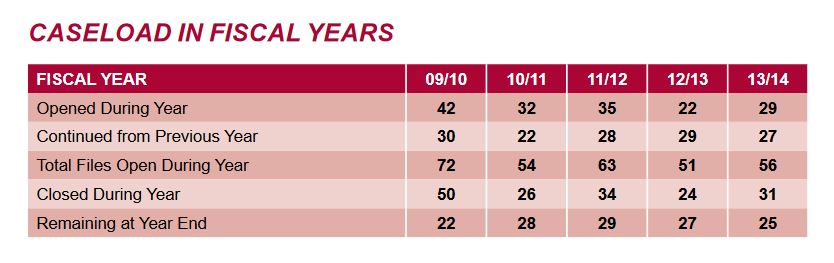

The website of the Ontario Judicial Council, the agency that looks into allegations of misconduct and disciplines judges, provides annual reports on its investigations but is years out of date. The last available report is from 2013-2014.

“Preparing an annual report includes writing, review for accuracy, translation into French by a certified translator, production and printing,” council registrar Marilyn Bell said in an email.

“The mandate is to make the report after the end of each year. Every effort is made to send the report to the Attorney General as early as possible.”

The Ministry of the Attorney General said currently there are no rules requiring timely public reports, but the Standing Committee on Public Accounts is drafting recommendations for the province.

“The province recognizes the importance of publicly available annual reports, and that timely access to information is key to empowering citizens to know about the organizations that serve them,” spokeswoman Emilie Smith said in a statement. “We continue to strive to improve transparency and accountability.

“In general, however, we can advise that there is no statutory or regulatory requirement for when the Ontario Judicial Council’s reports must be filed.”

Of the 56 complaints received in 2013-2014 or carried forward from previous years, 29 were dismissed because they were found to be either outside the council’s jurisdiction, unfounded or not judicial misconduct. Twenty-five were carried over to the next year. Only two were referred to a Chief Justice, meaning the panel believed there was merit to the complaint.

The judge’s name is not released unless there is a public hearing. Between 2002 and 2014, there were only eight times when a judge was named.

Butt said unlike police, doctors, teachers and other professions, complaints against judges are dealt with in virtual secrecy and often decided by fellow judges.

“Every other profession has evolved to the 21st century. Judges seem to be the last holdout,” he said.

“They are the ones who decide all the tough issues that arise in every other context. I guess there is a bit of reluctance to turn the spotlight that they put on other areas, onto themselves. But it’s important that that happens. It’s far too secret.”