Human trafficking in your backyard

Posted October 17, 2021 2:28 pm.

Last Updated October 21, 2021 8:31 am.

WARNING: This story contains graphic content related to violence and abuse, and may be disturbing to some readers. If you or someone you know may be a victim of human trafficking, you can call the Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline: 1-833-900-1010

“We lost two girls through that place right there,” Megan Walker said pointing out a fast food restaurant near an exit to Highway 401. “Two girls lured from the cash register.”

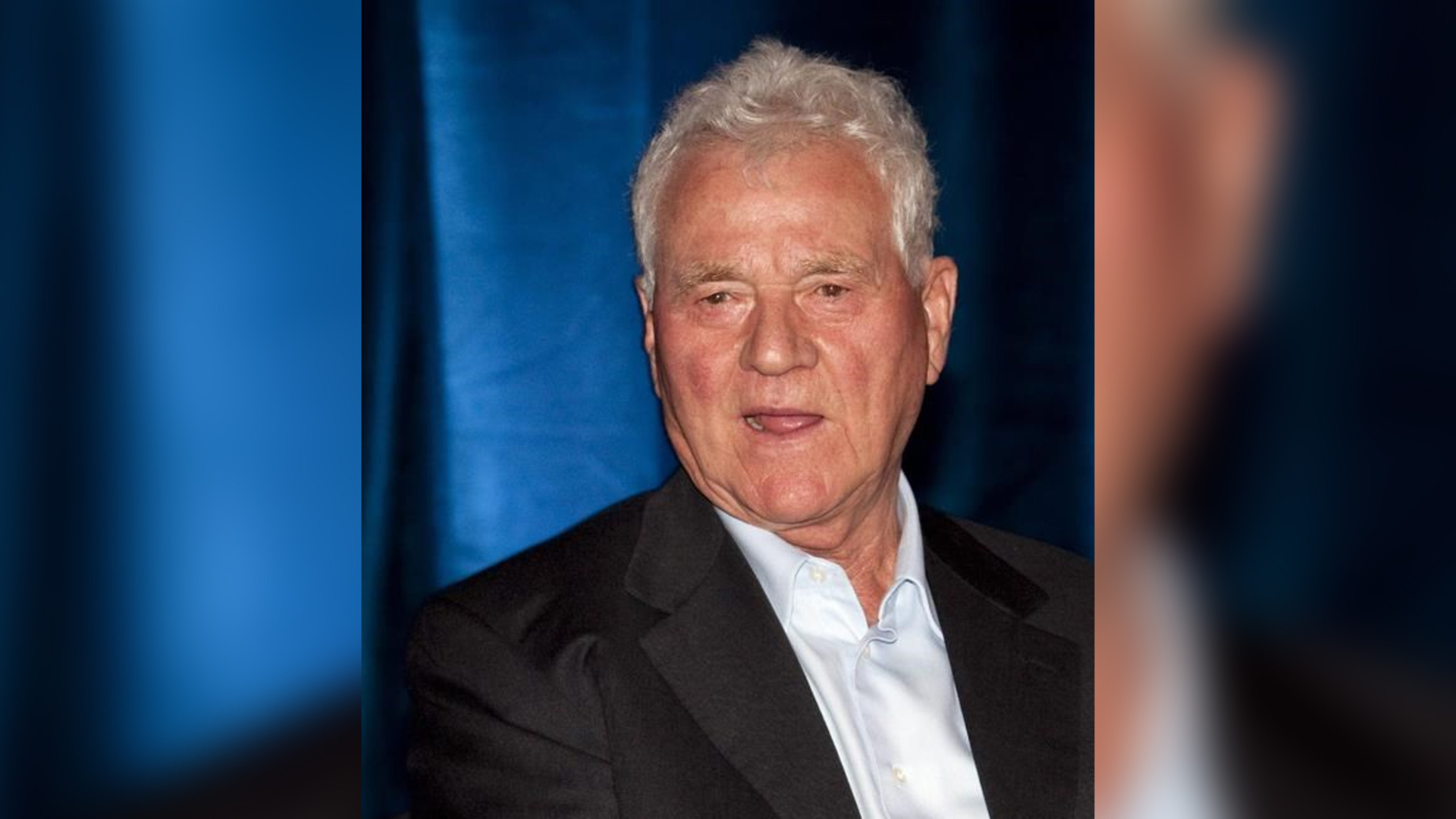

Walker is the recently retired Executive Director of the London Abused Women’s Centre. Over a decade ago, she expanded the centre’s focus from victims of domestic abuse, to advocating for and supporting victims of male-dominated violence, including trafficking survivors.

Over the course of several weeks, Walker took the “VeraCity: Fighting Traffic” crew for a tour of local trafficking hot spots – the massage parlours, the hotels and the nieghbourhoods where victims are often forced to work. She knows these roads as Walker has been driving them for years, looking out for traffickers, johns and victims.

“Sex trafficking is the deliberate, manipulative, deceptive means to lure women and girls into a situation where they’re providing sexual services against their will,” Walker explained.

Concrete statistics aren’t available, because most victims don’t go to the police and if they are able to leave, don’t access services where they can be counted.

Data from Statistics Canada indicates that 95 per cent of police-reported incidents of trafficking in 2019 involved women and girls. The Centre to End Human Trafficking puts that number closer to 90 per cent, based on data from service providers and police. Most are Canadian, 86 per cent, and nearly 90 per cent are under the age of 35, with 21 per cent underage.

Indigenous women and girls are overrepresented in this group, and according to the Centre to End Human Trafficking, are more likely to be trafficked after travelling to urban centres from remote communities to begin school or seek out employment opportunities. The average age of a trafficking victim in Canada is only 17, and can be as young as 13.

“Many families have lost a daughter to a trafficker, Girls who may have never even had sex before,” said Walker.

She is surveying a particularly seedy hotel – a chain hotel – located right off the 401, one of the busiest sex trafficking corridors in Canada. We watch as a woman exits the hotel with a child on her hip.

She brings the toddler to a man who has been sitting in a parked car, engine running, since we arrived. She isn’t his first visitor. She hands over the child and walks back in the hotel with a man that arrived in the lot a few moments earlier.

“Traffickers are often meeting particularly young girls online, and that’s how they are luring them and getting them involved. Through manipulation and deceit,” Walker explains. “It’s all online forums. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, all of them.”

The woman comes back to the van. Her companion exited the hotel a few moments earlier. She takes back the child and chats with the man in the car for a few minutes before heading back inside with the baby.

Sex trafficking is rampant. Statistics Canada reports that in 2019 there were 511 police-reported incidents of human trafficking – a 44 per cent increase over the year before – but, again, most cases aren’t reported to police.

The London Abused Women’s Centre saw 1,220 unique human trafficking victims between January 2020 and June 30, 2021 in just one of their programs. During that same time period, London Police only laid 28 trafficking charges.

The Centre to End Human Trafficking has tracked six key routes for traffickers – the 401 corridor from Windsor through to Montreal, the West Coast circuit, the Trans-Canada highway, Calgary/Fort McMurray, Northern Ontario-Winnipeg and Nova Scotia/New Brunswick. Most often victims are transported by car and are driven by the trafficker.

While movies and mass media culture may have primed people to see trafficking victims as kidnapped off the street and forced to service people while chained to the bed, that’s not often the case.

While organized crime—biker gangs, street gangs – have a strong foothold in the trafficking world, the Romeo pimp is the most common. An estimated 25 to 50 per cent of traffickers are boyfriends or girlfriends of the victims, who may or may not have gang ties.

“My trafficker was my boyfriend,” Caroline Pugh-Roberts said, her undercut shaved head tied back in a long braid, donning a “Stop Human trafficking” shirt. “Eight years – up and down the 401.”

Caroline was 35 years old when she started being trafficked. “These traffickers … have an innate and astute ability to sense and smell vulnerability.”

In Pugh-Robert’s case, it was grieving over the deaths of her husband and mother. In many other cases, it’s prying on young women’s self-esteem, body image issues or socio-economic and family struggles.

“They think they are in love,” Pugh-Roberts said. “I had nothing and I came to believe the only reason I was alive was because of my trafficker.”

Pugh-Roberts said it started small – her trafficker was out of work and they needed money for rent. He asked her to dance at local strip bars so they could quickly earn some cash. She hadn’t done it before and didn’t want to, but “thought I was doing for family. This is what family does.”

It turned ugly – fast. She had quotas.

“I never had a quota [of] less than $500 a night, sometimes more,” said Pugh-Roberts. She also quickly learned that meant doing much more that just taking off her clothes. “Anybody who tells you that stuff is not happening in strip bars either has never been or is lying. Everything goes on in strip bars.”

Pugh-Roberts takes us to a strip bar located on a rural road, surrounded by fields of crops, hobby farms and the occasional sound of horses and cows. It’s in the middle of nowhere. This was her home base.

“If I didn’t make enough money inside the club, I would have to come to the parking lot,” adding she would do whatever it took to make sure she brought home her quota. “I never went home without it.”

When she tried to leave, her trafficker broke all her toes. “That’s when he started bringing customers, johns, whatever you want to call them, to the (motel) room. It just got worse.”

She eventually got out, but not before having several bones broken, developing an addiction, and having parts of her body amputated.

“When I left, I wasn’t me. I had PTSD, trauma. I don’t want to say I was broken, because women don’t break, we bend. But I was bent. A lot.”

Pugh-Roberts now works for the Salvation Army’s Human Trafficking division, helping trafficking victims escape, and supporting them after they are out.

A car ride with Caroline feels like a car ride with a 911 dispatcher. One of her two phones is always ringing. She often makes it only a few blocks before she needs to pull over on the side of the road to try to triage survivors’ emergencies and needs.

This could include a safe bed for the night, access to methadone to keep them away from opiates, groceries, clothes for a job interview, access to crisis counselling, or help getting home from a hospital hundreds of kilometers away.

“Most of the women and the men that are being trafficked do not self-identify, because the word trafficking was never in my vocabulary. I didn’t know about trafficking. If you used the word trafficking to me, I would have like stared blankly,” Pugh-Roberts explains on a rare break between calls. “I knew I wasn’t happy and I knew I was doing stuff that I didn’t want to be doing.”

Part of her job is helping people come to terms with what’s happened to them. Pugh-Roberts says she knows some people choose sex work as a job, but most aren’t there by choice. Walker agrees.

“There are women, who are largely high-end escorts, who are making a lot of money,” Walker starts. “But the evidence supports that the overwhelming majority of women and girls who are in prostitution are not there by choice. And the relationship between prostitution and trafficking is fairly clear.”

“Trafficking is easier than smuggling guns. With women you never run out – your supply doesn’t cost you anything and they are everywhere,” Walker said.

“One girl can bring in $250,000 to $300,000 a year for a trafficker … Think about the number of men that have paid to rape those girls and women.”

In part 2 of the Fighting Traffick series, CityNews looks into where human trafficking is happening and why it’s so difficult for police to lay charges.