Many Six Nations of the Grand River residents live without direct access to clean water

Posted August 30, 2022 2:54 pm.

Last Updated August 30, 2022 6:01 pm.

In a new series, CityNews will be talking to Six Nations community leaders, residents and water keeper Autumn Peltier about efforts to get every resident access to clean water and why this issue is proving so hard to solve, Canada-wide.

Just two hours outside Toronto, more than 2,000 households on Six Nations of the Grand River live without a basic human right: clean water.

Some residents can’t simply fill up a glass at their taps and drink, take a shower, or bathe their children without worrying about the water being contaminated.

“We’re doing our best to progress our community as best as we can. But there comes challenges,” said Chief Mark Hill. “One of those challenges is the access to clean drinking water, potable water.”

The community is one of the most populous reserves in Canada with close to 18,000 residents. Unlike 27 other indigenous communities across Canada, the reserve is not under a federal long-term drinking water advisory.

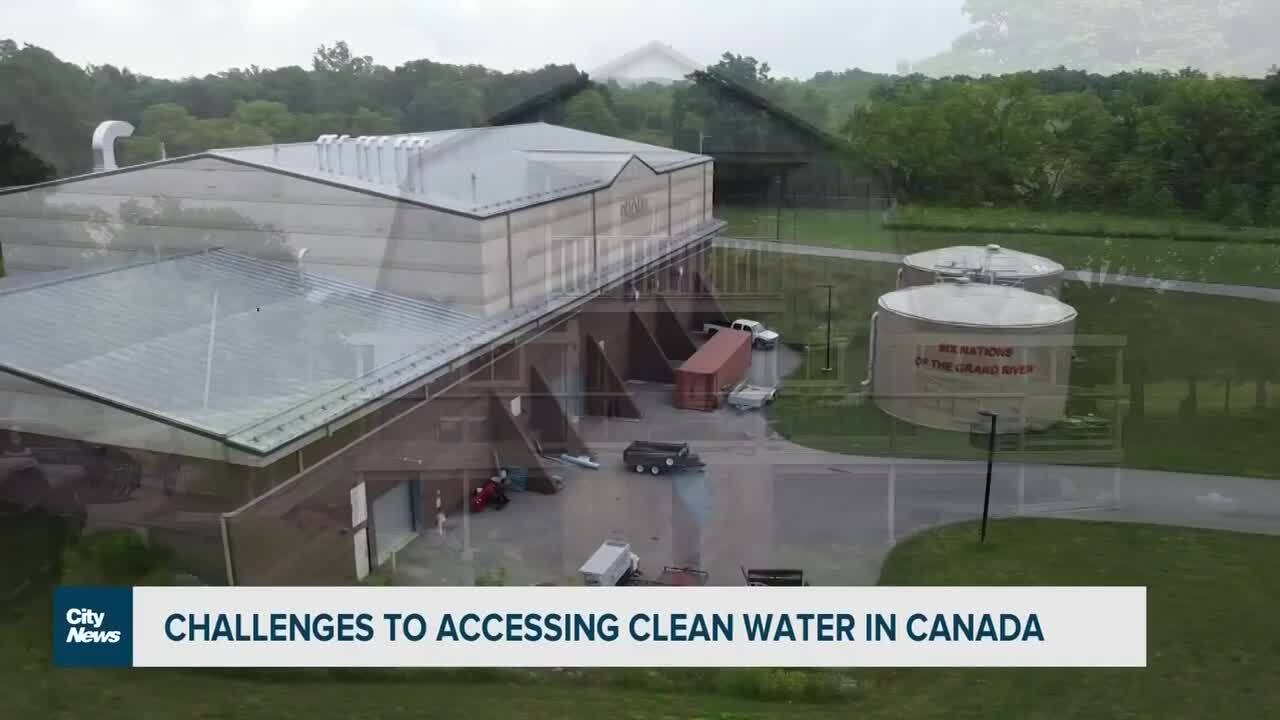

In 2013, a water treatment plant was built on the reserve, at a cost of $41 million. The federal government contributed $26 million, while the reserve’s elected council contributed about $16 million. As of 2022, it only provides water directly to 17 per cent of households.

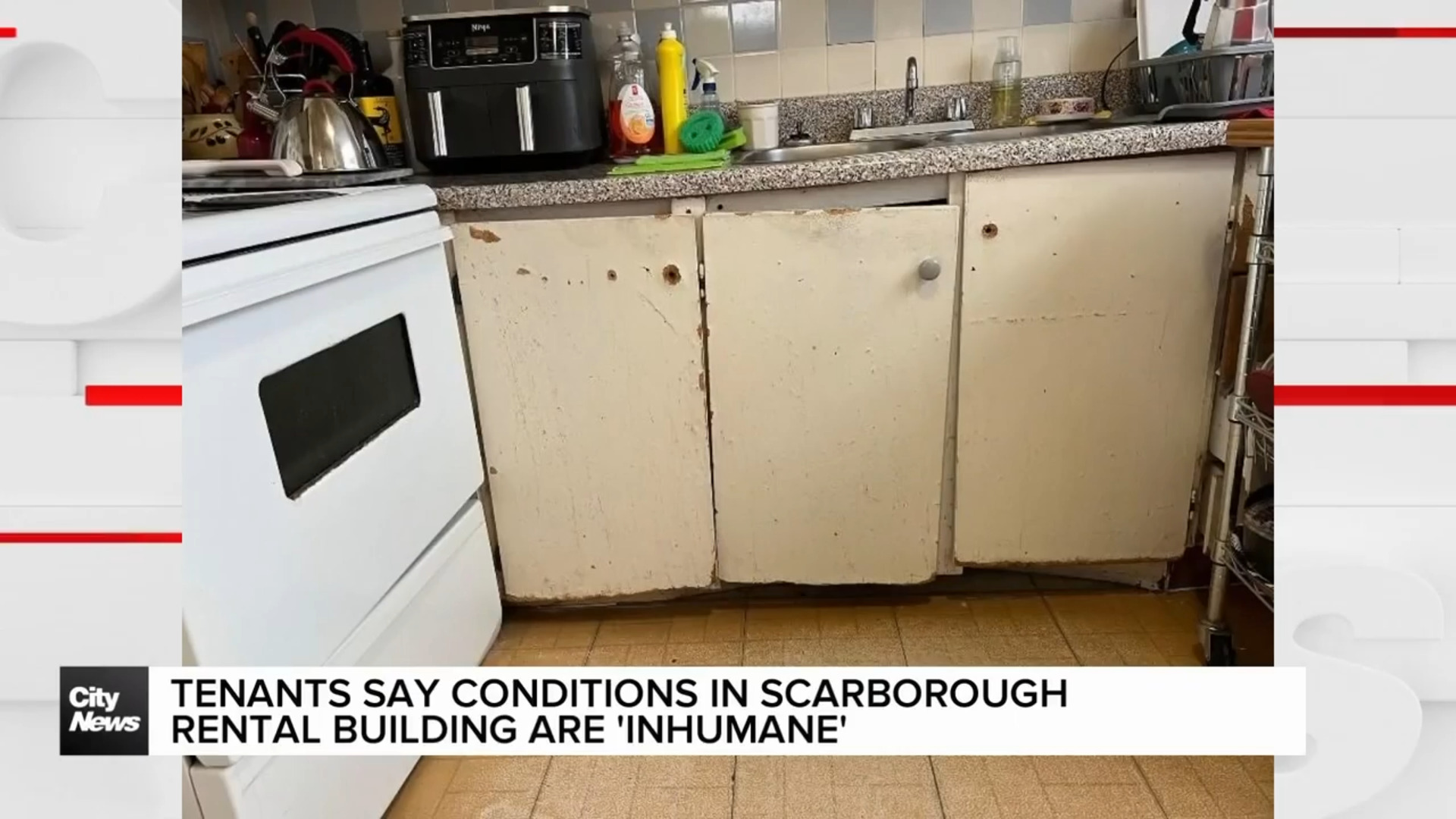

Much of the community uses cisterns, which are underground containers that can be filled with water that’s brought in by truck. Other residents receive their water from wells. However, both sources are open to contamination, so those residents often buy bottled water for consumption. Hill estimates that households spend an average of $2,500 on water a year.

Beverly Maracle, who has lived on the reserve for 50 years, has been without clean drinking water for the majority of her life.

“My homestead, we didn’t even have running water, so we didn’t have running water until I turned about 17,” she told CityNews. “Before that, we had to boil water and put it in the tub […] for drinking water,” she said.

Today, she draws her water from a cistern, noting “it’s still not as clean as it could be.”

CityNews was present when a temporary water filter was first installed in Maracle’s home. The filter is part of an initiative from the Dreamcatcher Foundation, in partnership with Healthy First Nations, to help those who can’t connect to the water treatment plant gain access to clean water.

“I can use the filter and drink a lot of tap water now. I don’t have to worry about having to get jugs or running out of water from the jugs,” said Maracle.

The filter is expected to provide at least 10 years of clean water if cleaned properly daily.

“I think this program is good,” said Maracle. “I have a friend that works for the program and she’s given me plenty of information about the water filter. So I feel that I can trust the water filter and will drink from it.”

Hill tells CityNews that the community has to get creative in order to bring clean water to their community and that is what Dreamcatcher is doing with these filters.

“Dreamcatcher has always been an organization that is has a mandate to inspire,” he said, “It’s even further inspiring that they come to the table and have an interim solution to our long-standing issue.”

He adds there will always be skeptics, due to the many years indigenous communities have struggled without clean water.

“This is the reality we’ve always lived in,” he said. “It’s hard to break through from reality.”

Government’s response to Indigenous communities without drinking water

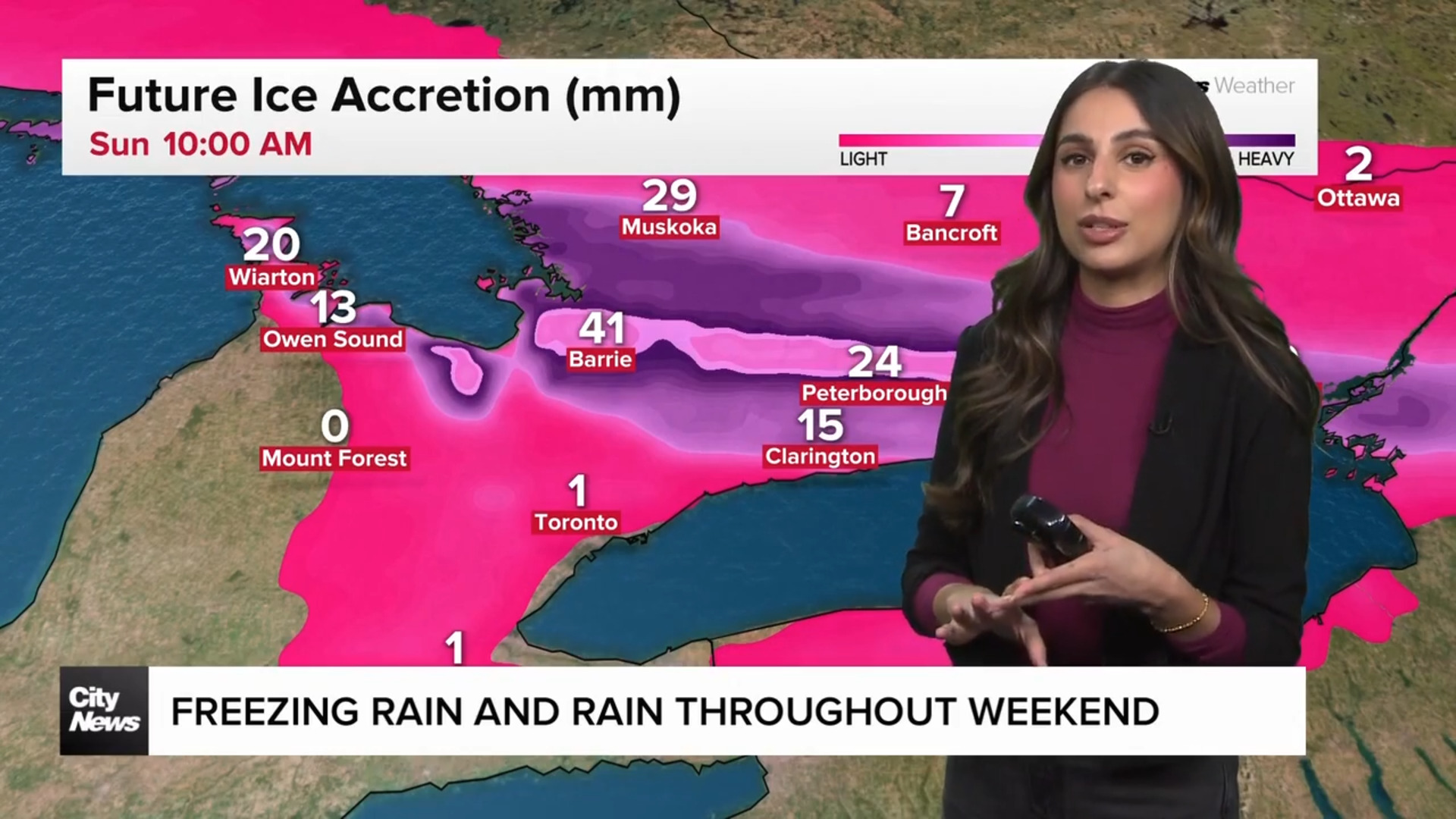

Many Canadians assume the communities under boil-water advisories are in remote northern regions. However, Six Nations is just a few kilometres away from major cities like Hamilton and Toronto.

A map of how close Six Nations of Grand river is to other major cities in southern Ontario. CITYNEWS

They were put under a boil water advisory by a former Six Nations health director in 2004, but has since been lifted.

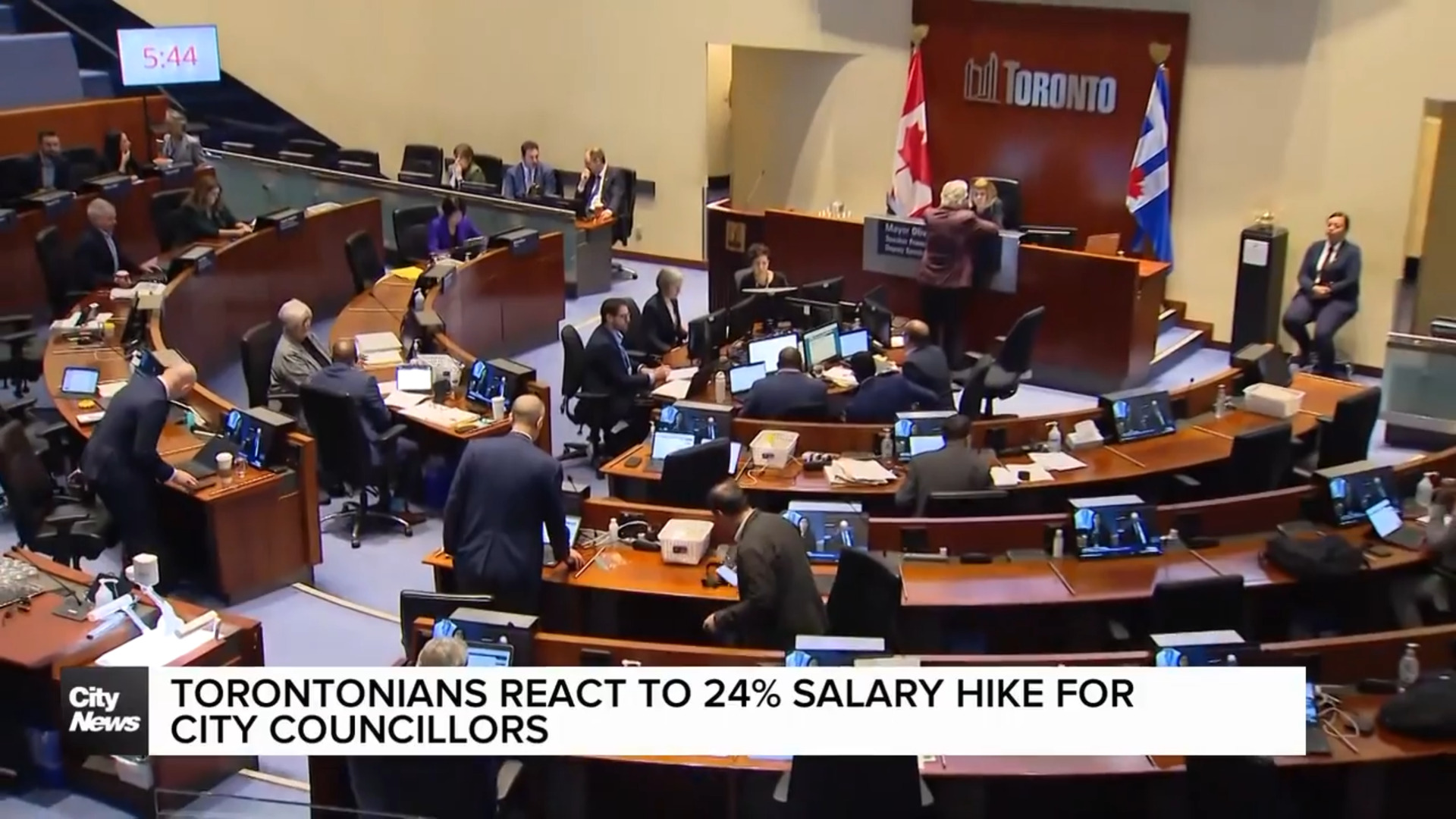

According to the federal government’s map, there are 31 long-term drinking advisories in effect in 27 communities across Canada.

The communities in Canada currently under long-term drinking advisories. CITYNEWS

Chief Hill said they are reliant on the grants and subsidies from the federal government to progress the work on watermains and the water treatment plant.

“The government, all the time speaks of reconciliation and [for] this government, there’s no more important relationship than the relationship with Indigenous peoples,” said Hill. “Yet we’re the largest reserve and we still have people living in poverty. We still have people with no running water into their homes.

Six Nations of the Grand River’s current water service strategy is to keep subsidizing watermain connections to homes from the water treatment plant. Hill notes that depending on how far away a resident lives from the facility, the cost for the connection can be many thousands of dollars. The reserve estimates in a policy document that the cost for a single phase of connecting homes is more than $80 million.

There are also efforts underway to build a extension of the water treatment plant that would service the southern part of Six Nations, but the estimated cost is $75 million.

In 2018, The federal government funded the expansion of the treatment plant to two federally funded schools and 400 homes, but have not announced any further funding for the reserve.

“Minister Hajdu remains in regular communication with Six Nations of the Grand River as we work in partnership to find long-term solutions to ensure access to clean drinking water in their community,” read a statement from the office of the Minister of Indigenous Services, Patty Hadju.

The federal government also said it’s making significant investments in community-led infrastructure projects across Canada and has doubled operation and maintenance funding for clean drinking water since 2015.

With files from Jessica Bruno