The continuing search for missing children and unmarked graves

Posted September 30, 2022 7:07 am.

Last Updated September 30, 2022 6:22 pm.

Editor’s note: This article contains details some readers may find distressing

Canada continues to grapple with a cruel reality, as more unmarked graves and potential burial sites are identified at former residential schools.

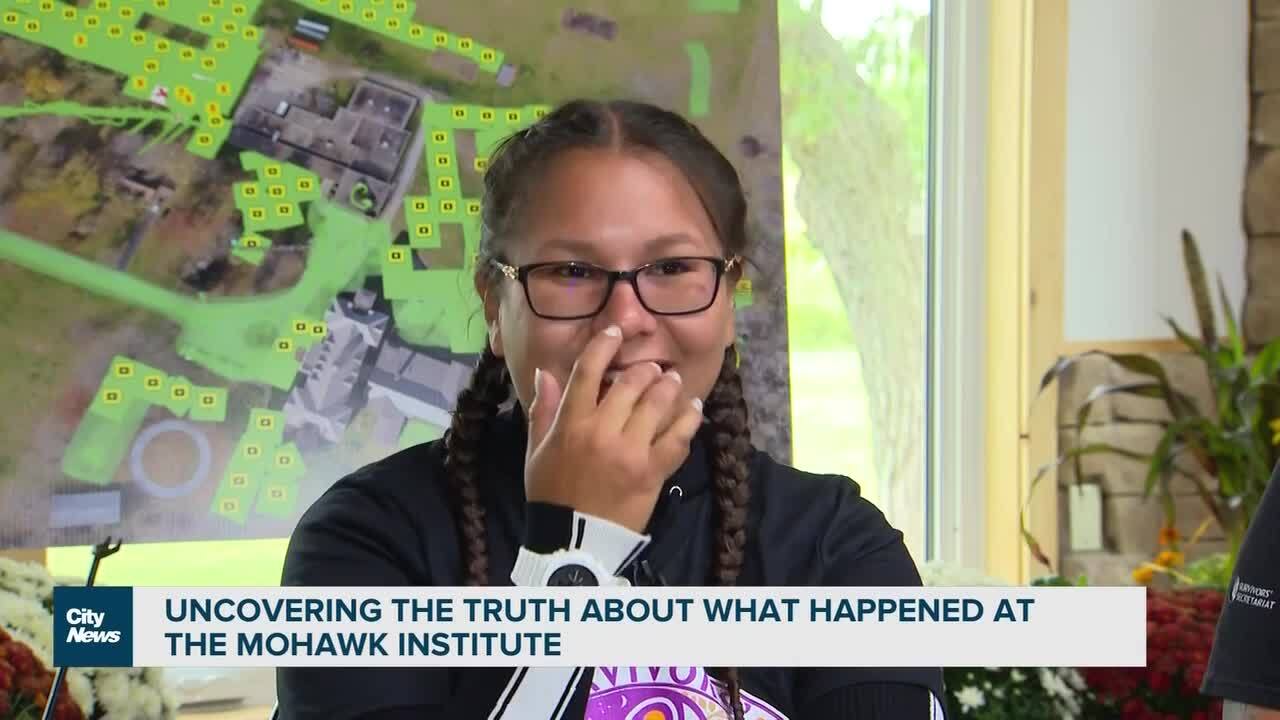

Communities across the country have made it their mission to search for missing children and burial sites, including at the former Mohawk Institute Residential School in Brantford.

The Survivors’ Secretariat was created for all Six Nations residential school survivors, including those who attended one of the longest operating residential schools in the country.

A team of post-secondary students joined in on the efforts to begin the search on the 600 acre property, including Dakota Sabourin, and her niece.

“It’s nice working with my family at the school, where they separated my family,” Sabourin says. “You weren’t allowed to talk to your brothers or sisters at all. So it’s nice working with her and having that family connection, when it was supposed to be destroyed in the school.”

A report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, estimates that at least 3,213 children are reported to have died at over 150 Indian Residential School locations. But that figure is a conservative estimate, mainly due to the lack of record keeping and documentation.

This year, several students signed up to help the Survivor’s Secretariat get answers, by searching the grounds of the former residential school. The commission has documented the names of 48 children who died while being forced to attend the Mohawk Institute, however, it is not known where they were buried, or if there are any others.

According to the Secretariat, survivors have shared stories of children suddenly disappearing, without anyone knowing whether “something bad happened to them or if they returned safely to their homes.”

“It justifies what the survivors have been saying, that there are people and kids who passed away at these schools and they don’t know where they are,” Sabourin says. “I got really sensitive over the summer, because it’s really hard. You don’t want to think about it while you’re doing it, but when you do think about it, you realize what you’re doing.”

Residential schools in Canada stripped First Nations, Inuit, and Metis children of their cultures, languages, and families.

In many cases, children were abducted and placed in these institutions, with no contact with their loved ones. Survivors oftentimes detailed the many forms of abuse that occurred in residential schools.

Then there were the thousands of students who never returned home. It’s these voices that the team of students, along with the Survivor’s Secretariat, are in search of.

“I felt very inclined to put my name forward to become a part of the work we’ve been doing,” says Jesse Squire, a member of the summer student team. “I’ve always been one to try and find the truth out and figure out what happened. My great-grandfather attended the residential school, so it’s been very important for me and my family to find out the truth of what happened, and where the children went.”

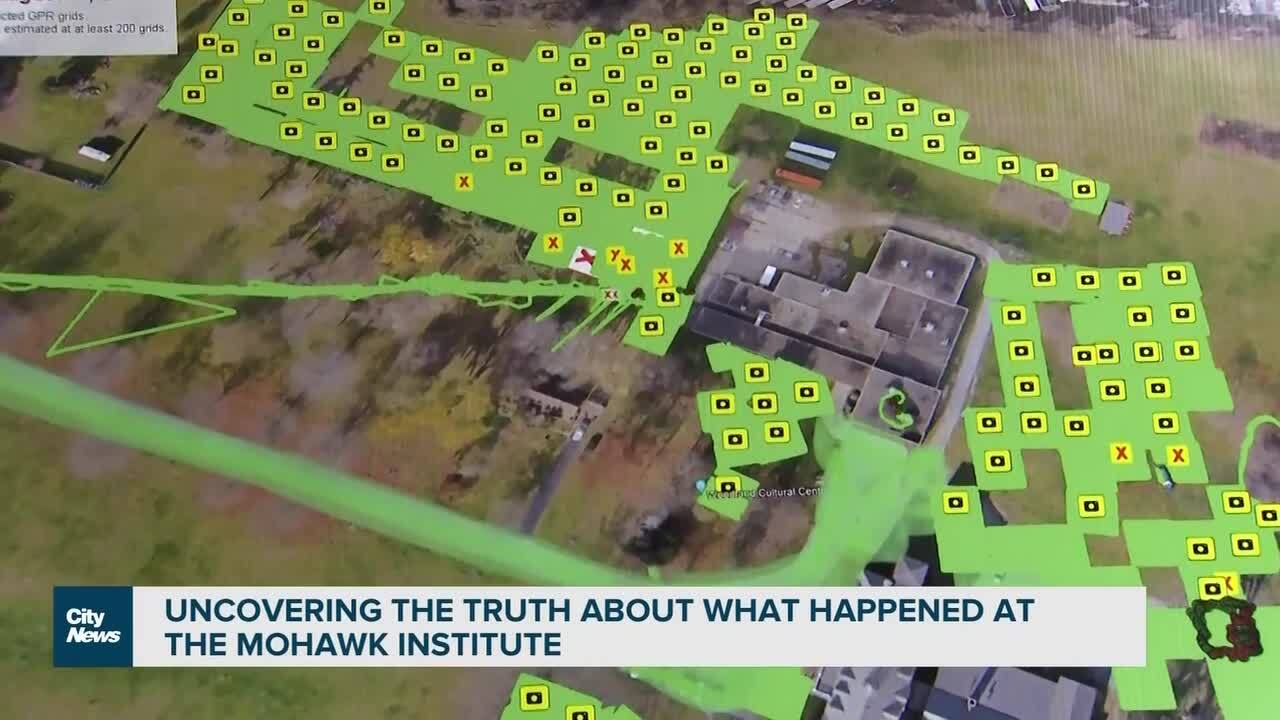

The students have been using ground penetrating machines (GPR) to scan the grounds of the former residential school property.

Between June and August, they’ve scanned approximately 1.5 per cent of the 600 acre property. The City of Brantford has also provided LiDAR scans, allowing the group to widen its focus to include additional areas at the Mohawk Institute.

“From June to the end of August, we completed 9.5 acres, so there’s a lot of work to be done,” Squire says. “We are getting one step closer to finding out the answer, and this is where it’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

“People want answers today, unfortunately we are in a marathon not a sprint.”

The students spent many scorching hot days pushing the 50-pound machine to collect data, which will then be analyzed and interpreted by experts. The Secretariat is working to determine a timeline of when the work will be completed, saying it can take years before they get the results.

“It’s hard work and healing work for our community,” Sabourin says.

The Survivors’ Secretariat was established in 2021, with the goal of organizing and supporting efforts towards uncovering and documenting what happened at the Mohawk Institute, which operated for 136 years.

The board of directors, which is solely made up of survivors who attended the residential school, is guiding and directing the work being done by the secretariat.

“One was my Grade 5 elementary school teacher,” Squire says. “Each one of them has their own story to tell, each one of them had their own experiences. I’m so grateful for it, it’s a lot of valuable information, a part of history that they’re willing to share with us.”

“A lot of them went to school with people who passed away at these schools, and they don’t know where they are,” adds Sabourin. “They get to have some answers on where they are, and it could be their own family members and friends.”

A Personal Journey

This undertaking comes with physical, mental and emotion hardships. There are also days, when the work becomes even more personal.

“I found a lot of my family’s school files online, it was a little hard because the youngest was four-years-old and she was my great-auntie,” Sabourin says. “People think it happened so long ago, when it only happened 26 years ago, the year I was bon in 1996. It wasn’t long ago.”

On those days, Sabourin says she cried a lot, reading what her family members went through at such a young age, being told that they couldn’t be themselves.

It’s why she speaks so passionately about her love of the Mohawk language, and her aspirations to help others learn it.

“It’s important to me to learn our culture and language, because that’s who we are,” she said. “Ever since I started learning my language again, it gave me a connection to myself. It is a spiritual journey.”

Sabourin, a second-year student at Six Nations Polytech University, is working towards getting her bachelor’s degree in Ogwehweh language and becoming a teacher. She never imagined her summer job would also provide her with a life-changing learning experience.

“I never really understood what intergenerational trauma was, until I started working there,” she says. “You feel guilt and shame speaking the language on the property, knowing that others were beat and told not to speak their language. It’s overwhelming, and a little sad.”

She, along with Squire, find comfort inside the offices of the Survivors’ Secretariat. They say they’ve formed a second family with the survivors, students and members of the organization, where they can find comfort on days that prove to be even more difficult.

But there’s also lots of joy and laughter in that building, as this newly formed family helps a community take a giant step towards healing.

“I don’t know how to describe it, it’s just been a whirlwind of an experience, working with these people, working with our survivors and getting back to the roots,” Squire says. “One thing I did realize working down here, is that it’s more than just the churches, it’s more than just the Canadian government, when getting down to the truth.”

Both students are hoping to return working on the grounds next summer.

Squire adds that he also wants more Canadians to get educated on the history of residential schools, and the impacts they’ve head on communities across Canada. He says he hopes more people come work together on this issue and share their stories year-round.

“Lets just close this dark chapter in history and work together,” Squire says. “I would encourage everybody to reach out to their local organizations, such has Survivors’ Secretariat if you’re in southern Ontario, whether it’s donating, volunteering your time, your resources or your efforts.”

The Survivors’ Secretariat has also established a Police Task Force along with a toll-free tip line to take statements from residential school survivors and anyone else who might have information. They can be reached at 1-888-523-8587.

Emotional support or assistance for those who are affected by the residential school system is available by calling the Indian Residential School Survivors Society’s crisis line 24/7 at: 1 (800) 721-0066.