Bible versus indigenous beliefs at issue in Bolivia

Posted January 24, 2020 11:06 am.

LA PAZ, Bolivia — Hoisting a large leather Bible above her head, Bolivia’s new interim president delivered an emphatic message hours after Evo Morales fled under pressure, the end of a nearly 14-year presidency that celebrated the country’s indigenous religious beliefs like never before.

“The Bible has returned to the palace,” bellowed Jeanine Añez as she walked amid a horde of allies and news media cameras into the presidential palace where Morales had jettisoned the Bible from official government ceremonies and replaced it with acts honouring the Andean earth deity called the Pachamama. The conservative evangelical senator, from a region where people often scoff at Pachamama beliefs, thrust the Bible above her head and flashed a beaming smile.

While Bolivians are deeply divided on Morales’ legacy, his replacement, a lawyer and opposition leader who wants to make the Bible front and centre in public life, is reigniting deep-rooted class and racial divisions at a time of great uncertainty in the Andean nation, where 6 in 10 identify as descendants of native peoples.

“It’s the same as 500 years ago when the Spanish came and the first thing they showed the indigenous people was the Bible,” said Jose Saravia, a civil engineer and married father of three children from La Paz. “It seems to me like the same thing is happening again.”

Like many in Bolivia, Saravia is a practicing Catholic who weaves in Pachamama beliefs passed down from this parents and grandparents. About 8 in 10 in Bolivia are Catholic, according to the most recent estimates.

Saravia and his family were among droves of people who came carrying their immaculately dressed baby Jesus dolls to fill a massive Catholic church in La Paz to participate in Three Kings Day masses on Jan. 6. As they slowly left the 18th century church, a Catholic priest splashed their relics with holy water.

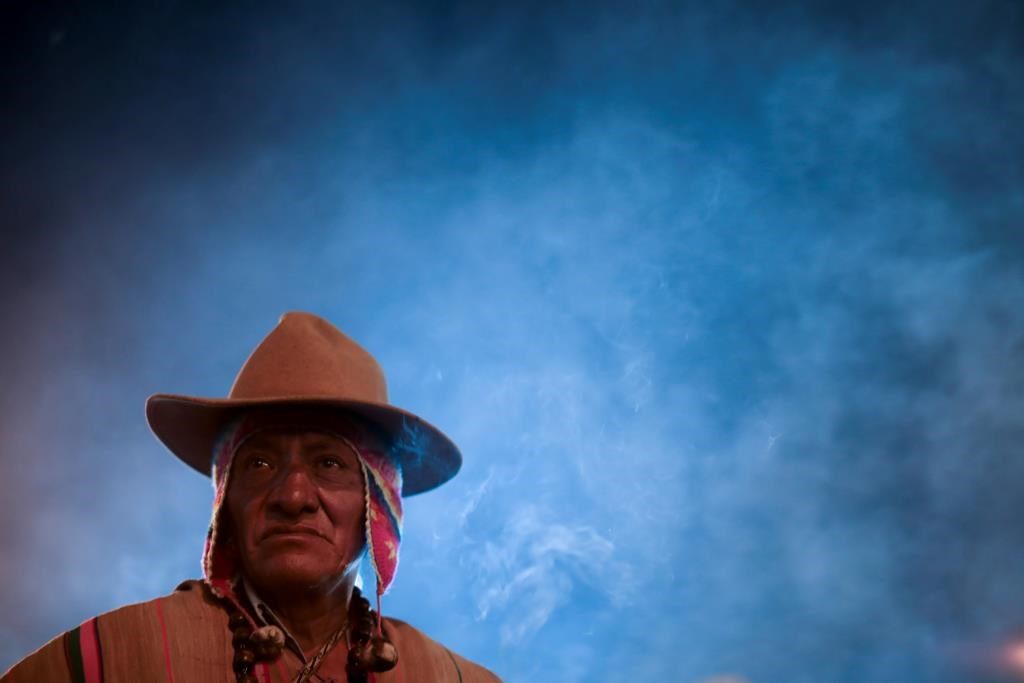

Just feet away from the church in a bustling plaza, parishioners stopped to have their baby Jesus dolls blessed by indigenous elders wearing their customary poncho sweaters and wool stocking hats in an act Bolivians believe shows respect for Pachamama and bring blessings in return. The men rang tiny bells as they placed the dolls in incense smoke billowing from small pots full of hot coals and special herbs, many ending the act with a sign of the cross and a kiss of a small cross.

A symbiotic relationship has emerged over time. It allows Catholics and Pachamama believers to maintain both systems, said Mariano Condori Flores, one of the indigenous guides doing the blessings. Flores uses a Catholic cross as part of the Pachamama blessing he gave the baby Jesus dolls.

Condori said the same relationship doesn’t exist with evangelicals, who tend to take a hardline against mixing beliefs and account for about 7% of the population, more than double their size in 1970, according to a self-reported membership figures compiled by the World Christian Database.

“It doesn’t seem like Añez understands that we exist,” Condori said. “She doesn’t talk about the Pachamama, she doesn’t talk about who we are.”

For many upper-class conservatives in the capital of La Paz, and in outlying provinces where people grew tired of Morales’ heavy-handed campaign to increase visibility and prominence of the indigenous religious beliefs, Añez’s reintroduction of the Bible is being celebrated.

“It was a demonstration of grand respect for Bolivian people. We are believers in God,” said Karina Ortiz Justiniano, a psychologist and mother from the province of Beni, where Añez resides. “The government of Evo Morales was way too aggressive, especially for those of us here in the oriental region that don’t believe in the Pachamama.”

Sentiments like that provoke strong reaction from Bolivians who embrace their Incan heritage. They fear that the discrimination they felt under previous presidents of European descent will return to this often overlooked South American country of 11 million people situated between Peru, Chile, Brazil and Argentina.

Morales raised the self-esteem of Bolivians of indigenous roots, allowing them to look the upper class, lighter-skinned Bolivians eye-to-eye, said David Mendoza Salazar, a Bolivian sociologist with expertise in indigenous culture. In Añez, many see a lighter-skinned, upperclass evangelical they don’t feel they can trust, and fear for the future.

“In the memory of the citizenry, the exploitation of the Spaniards is internalized,” said Salazar, from his home on one of the steep hills in La Paz, a city of about 900,000 people that sits at around 12,000 feet (3,660 metres) elevation.

Morales fled Bolivia in November after losing the support of the military and police amid widespread protests over a disputed election.

Añez will likely only hold the office until May 3, when the country holds another election, but critics say she represents Bolivian archetype that flourished before Morales became the nation’s first indigenous president in 2006. Indeed, one of the leading presidential candidates for the redo election in May, Luis Fernando Camacho, has built his campaign on bashing Morales and on the idea of restoring the prominence of Catholicism. Another candidate, Chi Hyun Chung, an evangelical pastor who campaigned against gay marriage and abortion rights on his way to finishing third in the annulled October election, described Pachamama beliefs as paganism and diabolic in an interview last year.

Morales commonly railed against what he considered discrimination that dated back to the Spanish conquest in 1520, describing his presidency as the “decolonization” of Bolivia.

Spanish conquistadors crushed strong resistance and enslaved hundreds of thousands of Aymara and Quechua Indians to work a huge silver mine as they settled the highland capital of La Paz. Until a revolution in 1952, indigenous people couldn’t even walk on the plaza in front of the presidential palace Morales occupied, let alone vote.

During a 2015 a trip to Bolivia, Pope Francis apologized for crimes of the Roman Catholic Church against indigenous people during the conquest of the Americas.

Morales revamped the Bolivian constitution in 2009 to formalize religious liberty protections and make the country a secular state, stripping special recognition previously given to the Catholic Church. None of the presidential candidates for the May election have unveiled their policy plans or talked about rolling back Morales’ changes to the constitution making the country religiously neutral.

Those protections give some relief to Margot Mejia, a Catholic who also believes in the Pachamama, but that Añez is evangelical gives her pause. Mejia spoke while chewing coca leaves as she sat with other women at a cemetery in La Paz after doing an indigenous commemoration for forgotten souls: light candles and bunches of cigarettes, scatter coca leaves and pour alcohol on the ground in homage to the Pachamama.

“Obviously, she is not going to understand these things,” said Mejia, a street vendor and mother of two.

Añez declined to be interviewed by The Associated Press but told a Bolivian newspaper in December that she will respect indigenous beliefs. But she said if Christians like her had to endure the Bible being taken out of the presidential palace and respect that some people didn’t believe in God, now others should respect her devotion to God.

It remains to be seen how much more Anez will inject her religious views into her interim presidency. Since the dramatic display on Nov. 12 at the presidential palace, Añez has mainly refrained from using the Bible or discussing religion during public appearances. Her decision-making on how to handle the topic may be influenced by an emerging possibility that she may herself run for a full term in the upcoming election.

Many upper-class and conservative Bolivians consider indigenous beliefs to be culturally inferior to their European cultural traditions and push back against what they consider the “pollution” of their Christian beliefs, said Kenneth Roberts, professor of government at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

“The right-wing religious push is also a push to restore the old order and the old social hierarchy where white Christians were on the top and they are very wary of indigenous identities,” Roberts said.

More than 370 miles (600 kilometres) northeast of La Paz, in the tropical Amazonian region of the country where Añez is from, the Beni province, that push can be felt by residents who reject indigenous believe systems.

Illustrations of the indigenous culture that can be found throughout the capital city of La Paz and the adjoined city of El Alto — such as a checkerboard flag with rainbow colours called the Wiphala and women wearing traditional bowler hats, wide pollera skirts and embroidered shawls — are scarce in Beni. At the Three Kings Day celebration, there weren’t any indigenous guides waiting outside to do the blessings that were commonplace in La Paz.

Many locals in Beni get animated when talking about Morales and the leftist policies of his political party.

Justiniano said Morales’ presidency trampled on the belief in God. Her voice raised and she began waving her hands in disgust as she discussed Morales, using air quotes when saying “the Pachamama” while she spoke near the city of Trinidad’s central plaza. She recalled a government act there during the Morales presidency where they put fermented alcohol called chicha in clay pots and burned incense.

“We are a missionary country, we were evangelized,” said Justiniano, a Catholic. “We have our identity and that’s what this man (Morales) didn’t know how to respect. He played way too much with the concept of equality for the poor and indigenous when in reality it is not a problem here.”

Residents of the Beni province instead celebrate the colonization by Jesuits while weaving in some parts of the indigenous culture native to the region. Paintings of men wearing robes, cross necklaces and large head dresses with feathers while holding machetes adorn the town of Trinidad, paying homage to a customary dance done by indigenous people of the lowland region that is acted out each year at a festival.

Freddy Bruckner, whose descendants came to the region from Germany, said making the Bible more prominent was an important symbolic gesture.

“They didn’t like that the country was without a God protecting it,” said Bruckner, an executive in a forestry company.

Nena Suarez put it bluntly as she got on her moped in front of the Catholic church in Trinidad: “We don’t believe in the Pachamama here. They have their dances that they believe means they’ve achieved something. Here, there are other beliefs. God is the only one, the all-powerful.”

Añez has said she was baptized Catholic but is practicing evangelical, though her office declined to specify which denomination. Many evangelicals in Latin America often just call themselves evangelicals and don’t necessarily focus on a denomination.

Añez was a lawyer before getting into politics and has campaigned against gender violence. She also worked as a TV presenter and director of a TV station in Trinidad.

Edwin Sanchez Mansilla, who owns a shop in La Paz called “Question of Faith,” which repairs religious relics, said Añez’ celebration of the Bible returning ignited a spike in business as people felt compelled to connect to their religious roots. He said he’s not worried that Bolivia will lose its indigenous culture.

“We’ve had these customs for a long time, Evo Morales didn’t invent them,” said Mansilla, sitting beside the Virgen of Copacabana, the patron saint of Bolivia that was discovered and sculpted by an indigenous Bolivian after the arrival of the Spaniards. “With or without Evo, we’ll continue. We have strong roots.”

The weaving of Catholicism and Pachamama can be found on the shores of Lake Titicaca in the city of Copacabana. Bolivian families come to hike up a mountain overlooking the lake along a rocky trail dotted with large crosses.

At the top, they buy miniature replicas of houses and cars and place them in tiny plots of land next to a rock wall at the edge of the cliff overlooking the majestic lake. Indigenous spiritual guides toss coca leaves and pour beer, wine and alcohol on the dirt near where the replica cars and houses are surrounded by flowers and covered by colorful streamers. Similar to the ceremony on Three Kings Day, Bolivians do this to show their gratitude to mother earth and believe their hopes for new homes and cars will be granted in return.

Below the mountain in the town outside a large and elaborate Catholic church, people line up cars to get blessings from Catholic priests who splash holy water on the cars with a wand and say a prayer with the family. As the priests move on to the next car, the families spray champagne and toss flowers on the car and end it by lighting fireworks.

Marcela Chachaqui, of Oruro, Bolivia, has come once a year since she was 9-years-old and now carries out the tradition with her husband and three children. They hiked the mountain the first day of the trip and had their car blessed by the priest the next morning. She’s worried about a diminished emphasis on her country’s unique fusion of beliefs in the post-Morales era in Bolivia.

“You have to always believe in the Pachamama,” said Chachaqui.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through the Religion News Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Brady McCombs, The Associated Press