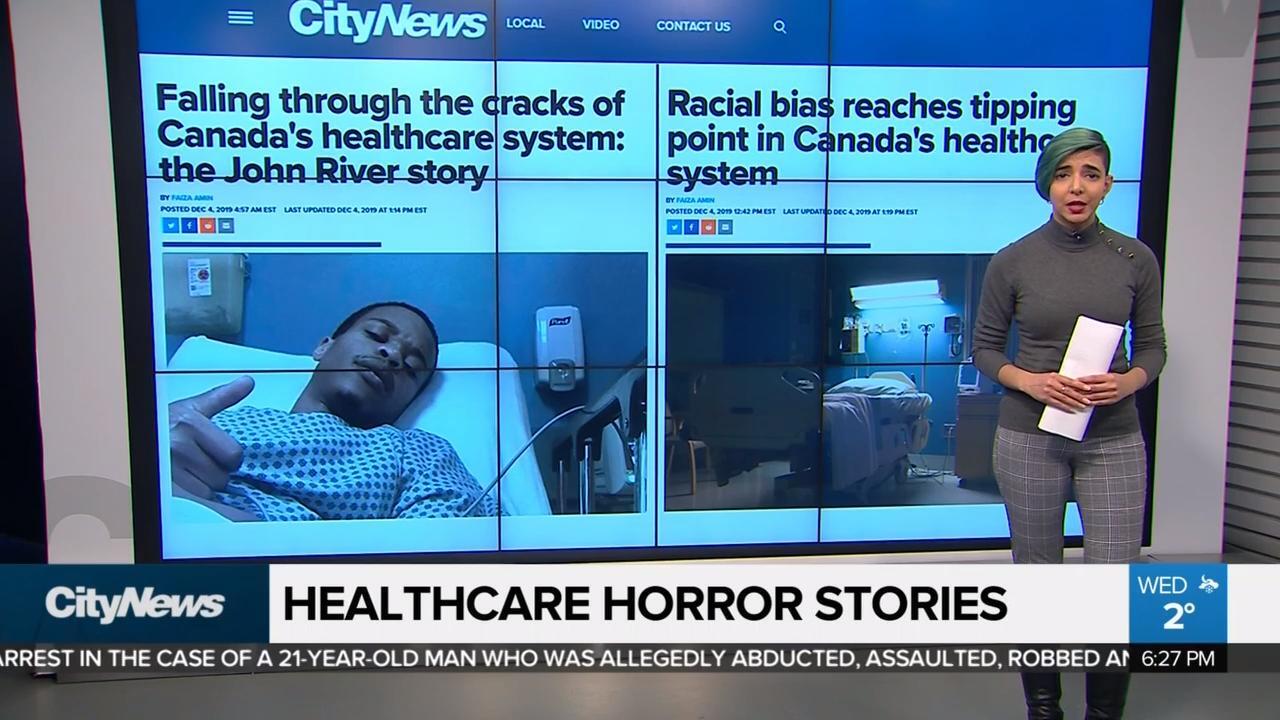

Falling through the cracks of Canada’s healthcare system: the John River story

Posted December 4, 2019 4:57 am.

Last Updated December 4, 2019 11:04 pm.

This article is more than 5 years old.

Award-nominated Canadian rapper John River has watched as public attention has shifted from his music to his struggle to navigate Canada’s healthcare system.

River, whose real name is Matthew John Derrick-Huie, walked into a GTA hospital in December 2017, complaining about shortness of breath and severe headaches. It was the start of a years-long health nightmare that he says demonstrates how he and others like him slip through the cracks of the healthcare system. And it has sparked a lawsuit against the doctor whom he alleges neglected to treat him.

“I feel like I was stereotyped, abused, assaulted, dismissed and humiliated by our healthcare system,” River tells CityNews in a one-on-one interview. “They kept telling me I had anxiety or depression … and I was imagining a problem.”

After that initial hospital visit, River says he was told to come back if the pain persisted beyond three days. It did, so he went back to seek treatment. He says on this visit, he was accused by a triage nurse of being a drug-user and faking his symptoms to get narcotics.

“I feel like they left me to die.”

On another occasion, he says he was also told he was experiencing anxiety and depression, but he “just wasn’t educated enough” to understand that the pain was all in his imagination. Finally, during another visit, a physician recommended getting a spinal tap procedure, where a needle would remove a fluid sample from his spine for testing. Health workers also warned the Mississauga native that the procedure came with risks: the tap could trigger a brain fluid leak, and experience symptoms that would make him “want to die.”

“They said it’s going to be the worst headache you’ve ever had in your life and you’re going to feel like you’re going to die,” he recalls. “If that happens, they said don’t panic, just come back to this clinic in 48 hours and we’ll give you a follow-up procedure called a blood patch to fix a hole that the needle left.”

Just one day later, River says he began experiencing those severe symptoms. He describes intense pain at the back of his neck, trouble seeing, and severe sensitivity to light. He went back to the clinic and he says was told that the doctor who performed that procedure was on vacation. River says he was asked to “sit tight” until he came back. So he held on, but when his physician returned, River says he still wasn’t given the procedure. He says he grew concerned as his symptoms worsened day by day, and his mom watched in horror as her 23-year-old son’s health deteriorated.

“I feel like they left me to die,” River explains. “I ended up getting that procedure over 60 days later.”

60 days of wanting to die

In those 60 days, River says he visited more than five GTA hospitals. There were a few doctors who acknowledged he needed the blood patch procedure, but who told him they couldn’t do it without special clearance, as the complications were caused by another doctor.

There were also doctors who didn’t believe River. He says those doctors accused him of exaggerating his symptoms as a cry for attention, or faking them to get access to drugs, or imagining them. On one occasion, River says he was admitted as a psychological patient for two days, because he rejected medication for depression and anxiety.

When at home, River would spend days in pain at the back of his closet as he became too sensitive to light. He started losing sensation in his hands and legs, and control of his bowels.

“I was in the hospital pretty much every night,” he said. “I would do anything on this planet to alleviate myself of this pain.”

During an appointment, River says he passed out. When he woke up, his mother and father were crying over him, believing their son was dead.

‘Losing Hope’

Frustrated with the health system, River’s mom and music team took to social media, pleading for help. They were inundated with well-wishers who were outraged by his experiences. Members of the black community who were familiar with the conscious and unconscious biases that exist in Canada’s healthcare system sent them advice. They were told that to be taken seriously and avoid discrimination, they would have to act in a certain way. He was told that as a black man, the way he and his loved ones acted and dressed at the hospital would impact the level of care he would receive. For example, they told River not to wear a hoodie or baggy clothing. They said his mom should be conscious of her tone so she wouldn’t get labeled as “an angry black woman.”

“You tell me if any white mother in this country has had to button up their unconscious child’s shirt because they didn’t want the doctors to think that their kids were selling drugs?”

With that advice in mind, the now 25-year-old tells the story of his mother trying to button a dress-shirt onto his body, as he lay unconscious on a stretcher waiting to be transported to the hospital. They hoped that this time that he would get treated instead of being accused again of faking his symptoms to get drugs.

“You tell me if any white mother in this country has had to button up their unconscious child’s shirt because they didn’t want the doctors to think that their kids were selling drugs?” he says. “For black people in this country, that’s the first thing they think about.”

As River’s ordeal persisted, his story spread nationwide, and he received support from other artists in Canada. During the Juno awards, Jessie Reyez posed in a photo with Humble the Poet, who wore a T-shirt that read “Don’t forget John River.” It’s this attention that River says finally led to help.

In February 2018 — nearly three months after he first asked for it — he received his epidural blood patch. This was the procedure he says he was supposed to get within 48 hours of his initial spinal tap. A neurologist later diagnosed River with Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak.

“I’m lucky and fortunate that people knew me in the community,” he said. “Within a very short time period, it was bureaucratically okay to give me this procedure, because in my opinion, I wasn’t just another negro who walked into the hospital. Now I was a negro with a name and a face.”

Canada’s broken system

Sitting inside a Mississauga recording studio nearly two years after that life-changing procedure, River says he feels fortunate to be able to get back to doing what he loves: music. But he’s still angry over how he and other racialized people have been treated by a healthcare system that is lauded around the world.

“Why did this medical system fail me in this fashion?” he asks. “There’s racial bias in every sector you look at and to think that the healthcare system would be impervious would be ridiculous.”

In late 2017, the then-Liberal Ontario government released a report that acknowledged a long history of racial biases that exist in the healthcare system.

The Ontario government says racial inequalities in the healthcare sector are most often indirect, subtle and systemic, but up-to-date data on discrimination in the sector isn’t readily available in Canada.

Watch below: Online readers weigh in with their own healthcare horror stories

Despite its universality, Canada’s healthcare system has become increasingly bureaucratic, and advocates say this can foster an environment where certain demographics are left out, particularly those who struggle to navigate services.

River says he is sharing his story for several reasons, including to raise awareness of the inequities that exist in the healthcare system.

Despite its universality, Canada’s healthcare system has become increasingly bureaucratic, and advocates say this can foster an environment where certain demographics are left out, particularly those who struggle to navigate services.

“What scares me the most: there are a million other kids who aren’t rappers, who don’t have the following I did,” he says. “I know that because those same people tell me they now need help.”

He’s encouraging everyone, not only the racialized communities who are disproportionately impacted by biases, to advocate for change. He says people should hold their local politicians accountable so that this issue is addressed by provincial and federal governments.

“I want people to be as angry as I am, maybe anger is a good thing and we need anger,” he said. “I will not feel good about myself if this happened to another black kid in the community and everyone is tweeting about it.”