Racial inequities driven deeper by COVID-19 pandemic, Toronto data shows

Posted July 31, 2020 5:20 pm.

Newly released race-based data on how COVID-19 is affecting minorities in the City of Toronto is shocking, but not surprising to the many Black health leaders who have been calling for the collection of race-based data since the beginning of the deadly pandemic.

As we learn that communities of colour make up 83 percent of the COVID-19 cases in the city, the question becomes: Why? And what’s next?

Toronto Public Health says data collected from people infected with COVID-19 and who voluntarily answered socio-demographic questions found 83 per cent identified with a racialized group. Seventy-one per cent of those who were hospitalized with the virus identified with a racialized group.

That’s compared with the 52 per cent of Toronto residents overall who identify as such.

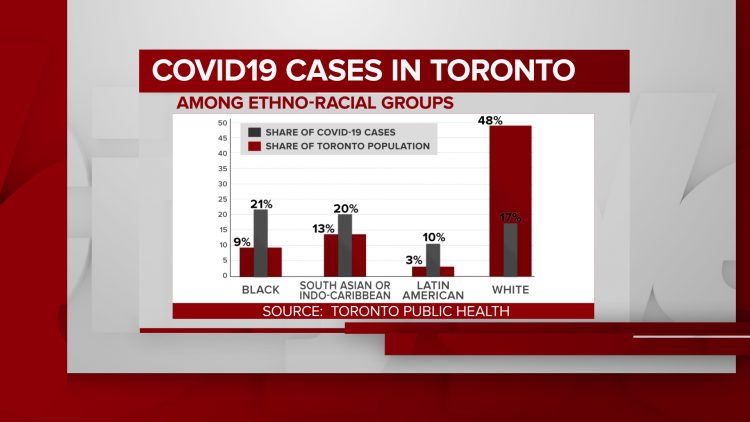

Twenty-one per cent of cases are in the Black community, despite the group only making up nine percent of the city’s population. South Asians and Indo-Caribbeans have 20 percent of cases with a population of 13 percent.

Latin Americans are three per cent of the population, but make up 10 per cent of COVID-19 infections.

White people who make up nearly half of the population with 48 per cent only account for 17 per cent of cases.

When broken down by gender, Black women made up 22 per cent of COVID-19 cases while making up only nine per cent of the Toronto population, the highest discrepancy within racialized groups male or female.

Eighty-two percent of women and 81 per cent of men who tested positive for COVID-19 and answered socio-demographic questions identified with a racialized group.

“We see an over-representation of racialized women in healthcare, and front line health workers and in nursing homes who are personal support workers,” said Dr. Notisha Massaquoi, a health equity expert.

Other factors include whether you can afford to drive or have to rely on public transportation.

The data also show 51 per cent of reported COVID-19 cases in Toronto were people living in households considered to be low-income, compared with 30 per cent of the population that meets the same definition.

More than a quarter – 27 per cent – of cases were in people living in households with five or more people.

Social determinants driving divide in health inequity

Social determinants include employment, whether you can work from home or how many jobs you may need, housing, socio-economic status, access to a vehicle, all of these factors contribute to how exposed one may be to the virus.

These factors put certain communities at greater risk.

“We have to start looking at how are we going to start addressing the large social determinants of health that are systemic,” Dr. Massaquoi said. “COVID is just an example. Any pandemic will show you fissures that exist in any society and the pandemic just cracks them open further.”

“We can’t ignore it anymore,” she added.

Dr. Massaquoi did praise Toronto’s Medical Officer of Health Dr. Eileen de Villa and Toronto Public Health for listening to advocates who wanted to see this data collected and how quickly they were able to see results.

“It was interesting they were able to do it in a rapid manner and such a well-developed manner, which also tells you the ability has always been there, it’s always about political will,” she added. “I think it’s really important for us to understand that the collection of this data should be seen as a benchmark moment and it should provide us with a blueprint of the collection of race-based data in health care, well beyond and above COVID.”

Social disparities already existed in health care long before COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to the spread of the virus, community health centres like TAIBU in Malvern and the Black Creek Community Health Centre were established to help these inequities in racializied communities.

Since COVID-19, TAIBU has launched a COVID-19 health line that provides access to a number of resource for the Black and Caribbean communities including testing, CERB benefits, employment support and other health services.

Executive Director of the Black Creek Community Health Center, Cheryl Prescod said they were not surprised by the data, but what they’ve been asking for plans and strategies to combat the inequities, adding racism is not a new issue.

“Community Health Centres were developed to serve the most marginalized communities. We know that we have to have a blend of clinical services and social services to address the social determinants of health,” said Prescod.

She added it was good to hear Dr. de Villa and Mayor John Tory addressing these social determinants. “We have to look at our communities to understand what the programs and service needs are so let’s do it, let’s fund it properly and equitably” said Prescod.

The province is now requiring all public health units to collect and report data on race, income, household size and language for those with COVID-19.

The Ministry of Health said they are working to share findings of the data collection after engaging with racialized communities, led by the Chief Medical Officer of Health.

“We are also engaging with people from racialized communities and other health equity experts regarding the use of these data. We plan to share findings of this data collection, informed by this engagement,” read a statement from the Ministry.

They have not provided a timeline of when this data may be available.