Indigenous, racialized, LGBTQ groups and sex workers criticize online hate bill

Posted April 23, 2022 4:00 am.

Last Updated April 23, 2022 2:11 pm.

Members of the LGBTQ community, Indigenous people and racialized groups fear a proposed law tackling online harm could disproportionately curtail their online freedoms and even make them police targets, responses to a government consultation have warned.

The documents, revealed through an access to information request, contain warnings that federal plans to curb online hate speech could lead to marginalized groups, including sex workers, being unfairly monitored and targeted by the police.

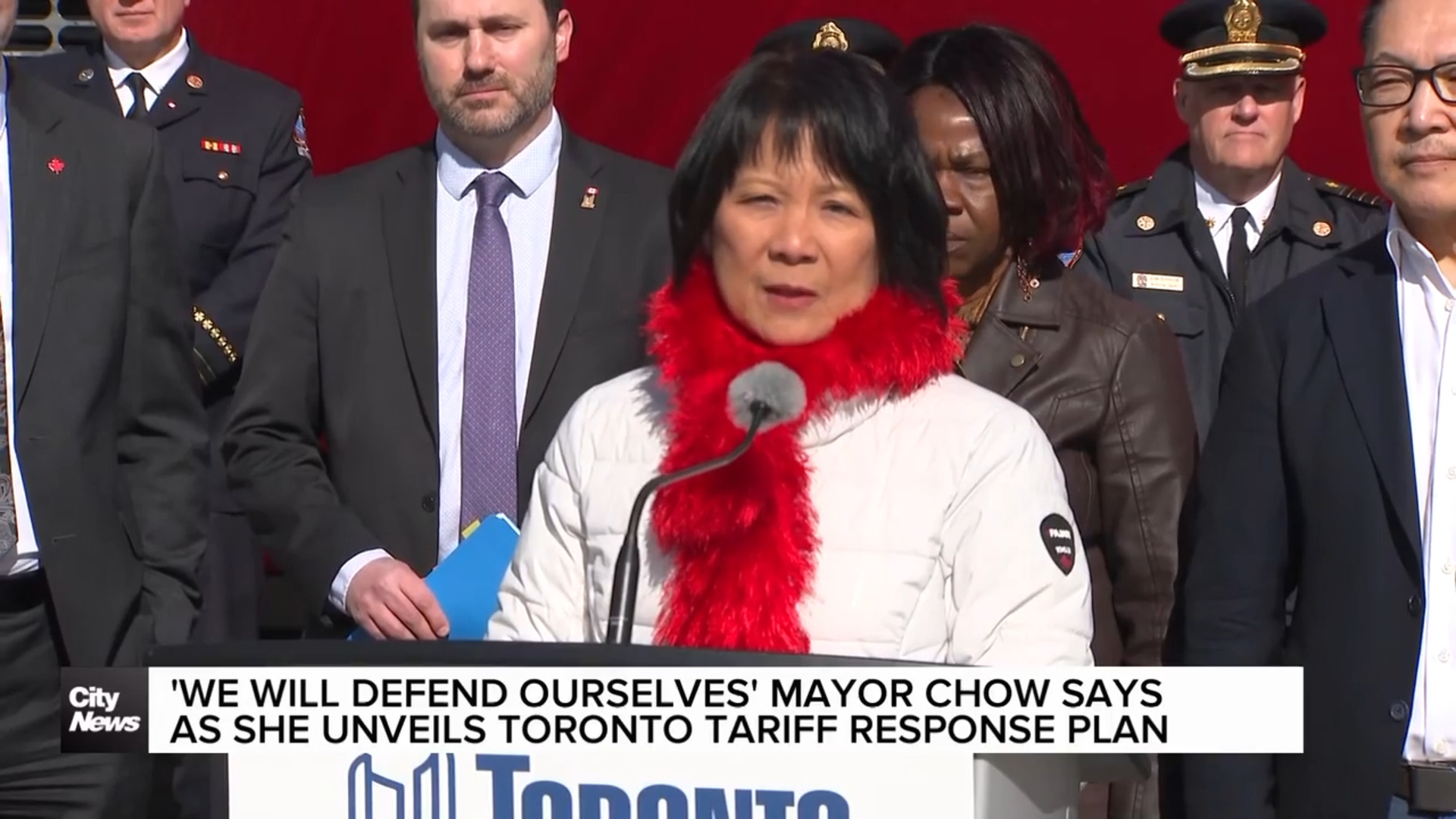

Plans for an online hate law, now being considered by an expert panel appointed by Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez, would give the Canadian Security Intelligence Service expanded powers to obtain subscriber information from companies. Online platforms may also have to report some posts to the police and security services.

A previous anti-hate law, introduced at the tail end of the last Parliament, died when the election was called.

The government began public consultations on an updated law before the election campaign and has said introducing a bill is a priority.

The feedback from the consultation, disclosed in the access to information request, is helping inform the expert panel set up by Rodriguez to consider how to frame a new law.

“While it is clear action needs to be taken on harmful online content we recognize the concerns expressed around unintended consequences if a thoughtful approach is not taken,” said Ashley Michnowski, director of communications for Rodriguez.

The law would be designed to clamp down on hate speech and abuse – including against women and racialized, Jewish, Muslim and LGBTQ Canadians – by blocking certain websites and forcing platforms to swiftly remove hateful content.

But Canadians from some of these groups said the internet is one of the few platforms where free speech is possible for them and that the law could curtail their rights.

Darryl Carmichael, from the University of Calgary’s law faculty, said in his response that the law risks curbs on racialized and marginalized groups, and could lead to their posts being misconstrued as harmful.

“Black Lives Matter posts have been mistakenly labelled hate speech and removed,” he said, warning that posts such as those raising awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls could also be removed.

“The result is that the voices of the very groups you seek to protect would be further isolated,” he said.

Sex workers from across Canada warned that such a law could lead to sites they use to carry out safe sex work online being shut down if they are captured by curbs on harmful online sexual content. They also raised fears of risk of arrest because of remarks made in their online sex work.

The Safe Harbour Outreach Project, advocating for the rights of sex workers in Newfoundland and Labrador, warned that the bill could lead to LGBTQ and other marginalized groups being disproportionately harmed as well as sites “crucial for sex workers’ safety” blocked. Its submission expressed fears the law could lead to censorship and mass reporting of many innocent people “already demonized … for their gender expression, race (and) sexuality.”

Some Indigenous people feared the bill could give more power to law enforcement agencies to target them, their speech and protest activities.

The National Association of Friendship Centres, a network of community hubs offering programs and supports for urban Indigenous people, said “Indigenous-led organizing, community and resistance have flourished online,” with protests about “resource extraction and development” relying on social media as “a significant part of their communication strategy.”

“These acts of resistance would easily be framed as anti-government or manifestations of Indigenous cyberterrorism,” it said in its submission, warning of a “risk of governing bodies weaponizing this legislation to identify protests as anti-government.”

Experts say an artificial intelligence algorithm may just pick on keywords, rather than the context or nuance of online remarks, leading to their being misconstrued and triggering the involvement of law enforcement.

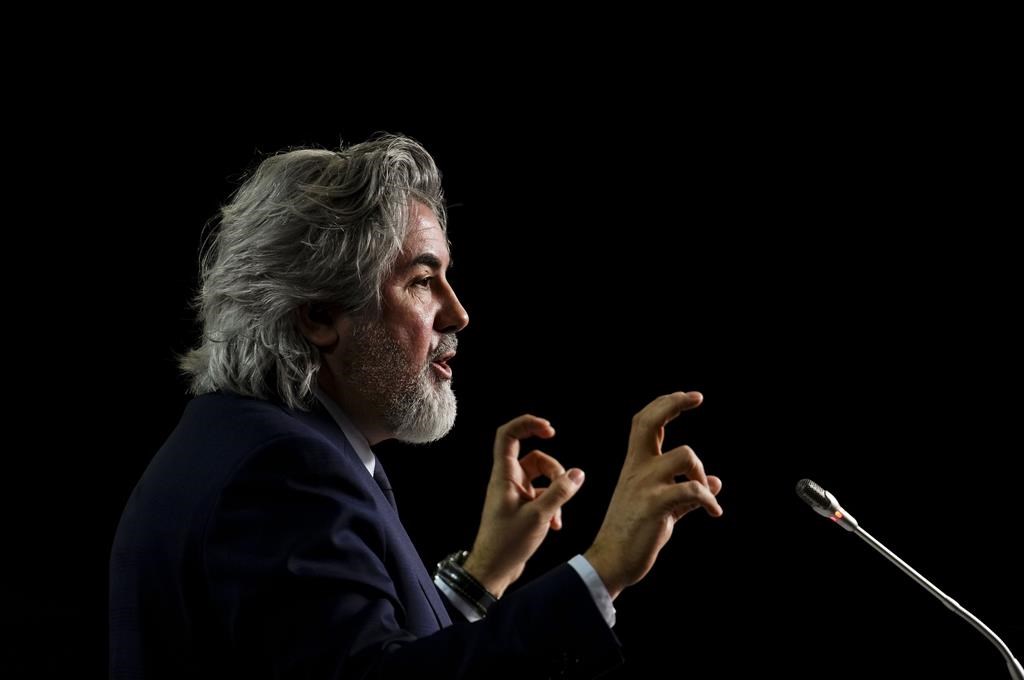

Michael Geist, the University of Ottawa’s Canada Research Chair in internet law, who obtained the consultation documents through an access to information request, said “leveraging AI and automated notifications could put these communities at risk.”

He said the level of criticism in the consultation, which includes a string of submissions complaining about curbs on freedom of speech, should be a “wake-up call for the government” that they are taking the wrong approach.

The National Council of Canadian Muslims warned that the government plans could “inadvertently result in one of the most significant assaults on marginalized and racialized communities in years.”

Richard Marceau of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs said a new law clamping down on online hate is necessary, but it “should be properly calibrated to combat hate and make sure that freedom of expression is fully protected.”

The centre’s submission said it is important that the involvement of law enforcement is proportionate and appropriate.

Laura Scaffidi, a spokeswoman for the heritage minister, said the government “took what we heard from Canadians seriously during the consultation that took place last year,” which is why it has appointed an expert advisory group on how to tackle harmful online content.

“We know this is an important issue for Canadians,” she said. “We will take the time we need to get this right.”