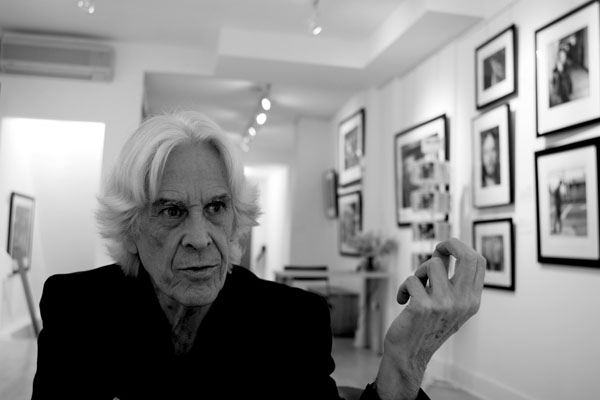

Local Character: Rock Photographer Barrie Wentzell Recalls A Life Among Legends

Posted December 1, 2009 5:17 pm.

Last Updated July 27, 2015 9:14 pm.

This article is more than 5 years old.

Story and photos by Michael Talbot, CityNews.ca

Long before frenzied paparazzi clamoured to snap coveted crotch shots of questionably talented divas slithering out of sinister stretch limos, Barrie Wentzell was down at the pub sharing a yarn and tipping a pint or two with a few of his mates — aspiring musicians who lived hard, practiced harder, and weren’t afraid to dream big.

And when some of those same mates became the superstars and icons they were destined to become, Wentzell followed them out on the road, his camera loaded with black and white film.

He likely could have propelled his own notoriety by snapping compromising shots as they engaged in the somewhat clichéd ‘sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll’ lifestyle, but Wentzell, refreshingly, wasn’t in it for the money or the fame. Unlike many of today’s tabloid-crazed photographers seeking the most scandalous payday, he had genuine love and affection for the music and the musicians who shaped popular culture in the 60’s and 70’s.

His take on photographic ethics is simple and honourable.

“Would you like that done to yourself?” he asks behind a perfectly 60s-looking shag of white hair.

“And that’s why I didn’t take a lot of pictures…there was many times when ‘Oh man if you had a camera,’ but I put mine away, because it was like you don’t do that, they are your friends and how would you like that happening to you?”

That respect and integrity shines through in his photos of legends like Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, and The Beatles, some of which are currently hanging at Toronto’s new Analogue Gallery at Queen and Bathurst.

“For me I’ve got to stand behind that…because there’s a certain ethic and principle of love, peace, truth, and honesty and all that, and you can’t sell it out. Money is useful, but it wasn’t an issue back then. Things were cheap and we somehow managed to get by.”

His musical journey began in many respects after a chance encounter with a young Diana Ross. Wentzell was in attendance for an episode of ‘Top of the Pops,’ and after she performed with the Supremes, he approached Ross and asked her politely if he could take a few photographs.

She obliged and he snapped away.

A journalist from the U.K.’s Melody Maker magazine was on hand, and suggested that Wentzell bring the photos in for a possible chance at publication. Wentzell didn’t think much of it, but those few frames would change his life.

“I dropped a few pictures in and the next week it ended up on the front page, and I ended up getting the gig because the previous photographer had been arrested,” he relays with an awestruck smile.

“I think (I photographed) Bob Dylan…just a bit after.”

Wentzell would end up shooting for Melody Maker from 1965-75, a period he calls a ‘decade long party.’

“It was really helpful because musicians wanted to talk to us rather than anybody else because we talked about the music and the reality and it’s fantastic to sit down with Hendrix, Clapton and Frank Zappa and whoever and just rap and chat, and that was an incredible freedom, there were no make up artists, no sort of management hassles, no contracts to sign, it was all virtually done for free.”

“It was like a whirlwind,” he adds. “Every day, every minute was full of something. I would maybe do about 3 or 4 photo shoots a day, and over the weekend I would have to be processing because it was real film, you’re lucky with digital,” he notes, eyeing my Canon DSLR with a curious disdain.

“And then in the evenings we’d all meet in the pub, it was like a load of friends. It was like you knew everybody, it was all a party and everybody was a part of it, the artists, the photographers, the musicians, the PR girls, and the record companies…there was that connection. Everybody was part of that party.”

The good times, however, wouldn’t last.

More than a few great talents were devoured by drugs and the rigours of the road and the ‘family’ atmosphere Wentzell sweetly reminisces about was soon obliterated by the divisive powers of money and greed. Wentzell saw the writing on the wall, and in the 1975, he bailed, moving with his daughter to the Isle of Wight, abandoning the music industry to work in his brother’s vegetable shop.

“Some of the people I was beginning to be asked to photograph, I thought, ‘Ah man that’s a bit plastic and pretentious’, and things were changing somehow, and some musicians had given up, I mean Peter Green grew his fingernails long and became a grave digger and gave up music.”

“I didn’t think music was dying, but it was changing and I couldn’t really beat to that drum.”

“The record business didn’t really re-invest, it ripped off a lot of the money, and a lot of my friends, the musicians, never got a penny. Jimi Hendrix might have had 50 quid when he died.”

Looking back on his own remarkable life and the lives of his many pioneering subjects, Wentzell seems somewhat torn between two trains of thought. On one hand, he’s very humble and casual about it all, as though his shots are merely some pics of his old friends. At the same time, he seems to understand that he’s captured some of the most significant portraits in rock history, and taking things ever further, he’s documented and taken part in an unprecedented cultural revolution.

“Who would have thought something we did 30 or 40 years ago would be sort of relevant now in some sense?” he asks. “I never imagined that.”

Rock n’ roll music was ultimately a magic carpet ride out of a mundane existence, for him, and generations to follow.

“Around 1955, when we were leaving school, you left school, then maybe went into a job and then you went into the army or the air force, you came out regimented and brainwashed and you carried on doing a mindless gig till you dropped. There was no youth culture, there was no youth fashion, there was no youth, you had school and then you were an adult, and then music and that came in and it gradually expanded into a culture.

“We were there to help create it, I guess, against many odds” he says, eyeing his majestic portraits.

“I think we can be proud of that.”