Programs working to end abuse by supporting men

Posted April 15, 2021 2:12 pm.

Last Updated April 15, 2021 2:14 pm.

A small team in Nova Scotia is working on big changes to the way communities hold abusers accountable for the harm they cause their victims, and it’s an approach they hope to see adopted Canada-wide.

“It’s really important that part of the work we do to end violence against women and children is to talk to men who are causing harm,” explains Katreena Scott, incoming director of the University of Western Ontario’s Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children.

It’s a difficult conversation, one experts say society isn’t having enough, and it’s leaving both victims and abusers vulnerable.

Abusers are “more likely to fall through the cracks,” Scott explains. “That leaves women and children left to pick up the pieces and try to figure out what to do, when the system isn’t holding them accountable.”

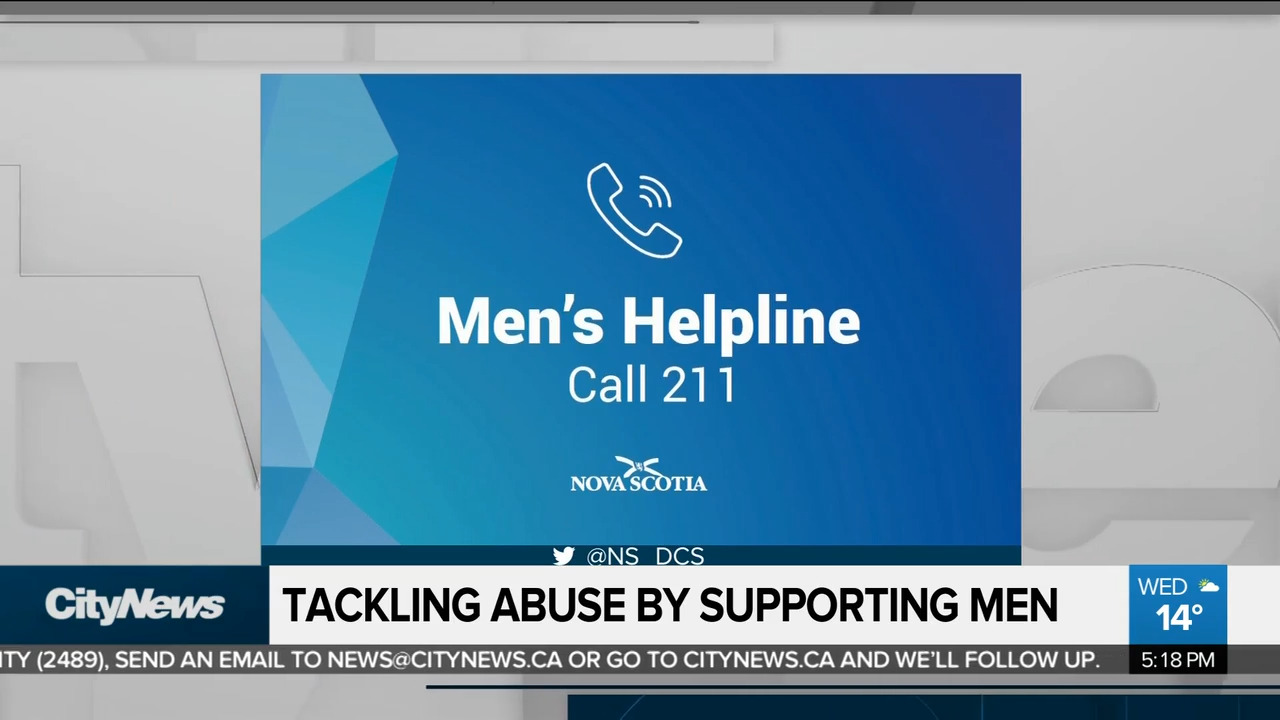

Frontline workers point out that programs available to abusers are usually court-mandated. Now there are efforts to intervene earlier. In September 2020, Nova Scotia launched a pilot 24-hour helpline, specifically for men, responding to an increase in calls for help.

“Our local 2-1-1 navigation system started to see an enhanced call volume from males and anyone identified as males,” explains Nancy Macdonald, executive director of Family Service of Eastern Nova Scotia.

The helpline is confidential, free, and available in multiple languages. It connects adults to both immediate support and long-term help. It’s a collaboration, costing about $175,000 to run, funded through a provincial initiative that focuses on disrupting the cycle of violence through transformative change.

“The underlying foundation is to normalize reaching out,” says Macdonald.

Since the launch, the service has received more than 850 calls. Those phoning in have been between 19 and 80 years old. Research shows their top reasons for calling include getting help handling stress, managing their emotions, and dealing with anxiety. Of the men surveyed, 95 per cent said the line was useful.

“I’m hoping it reaches people who never thought they could reach out for help or didn’t know where to reach out for help,” says Macdonald. She adds the pilot is showing that men will use support, if it’s available.

“It tells me we’re on the right track.”

Western University’s Scott will also be part of the team analyzing the hotline, and seeing if the program can be expanded beyond the province.

“There are few services like this across Canada,” she says. “If we start to include men in ending violence, it’s useful to understand what we need to do better.”

Scott says these transformative initiatives are just a piece of the puzzle, and there’s research to indicate they’re effective. She was part of a team that interviewed men who were arrested and deemed high risk by police, focusing on managing risk and ensuring safety of women and children.

“Over year years, following that, rates of repeat domestic violence perpetration were lower in those men that we were able to talk to as compared to a sample that we weren’t,” Scott says. “There’s some evidence, that if you provide resources and the option for help, men will take you up on that option. And if you then connect men with service providers who have the expertise to do this work, we can change the trajectories of violence over time.”

Rowans House society, an Alberta-based organization, just recently launched an innovative a 52-week program that removes abusers from the household.

The organization, located south of Calgary, provides crisis intervention, long-term support and education for victims and survivors of family and intimate partner violence in rural communities.

Last month, the organization launched ‘Safe at Home’, a four-year pilot project that is described as the first of its kind.

“The goal of this program is really that the abuser learns how to self-intervene and change his behaviour so that he’s not repeating behavioural patterns that he did in the past,” says Danelle Mirdoch, Board Chair with Rowan House Society. “So when that anger comes up or that tendency to abuse comes up, he knows how to change his behavioural patterns to act differently.”

The program operates in three phases. In the first eight weeks, the men, who are all self-referred, will have to live at a transitional home where they must comply with a series of criteria. During this period, the men will participate in a number of programs that address their violence, and they will only be allowed to communicate with their family over the phone or video chat, and not have any physical contact.

“The women and children don’t have to leave the family unit, they can stay there and have the stability and maintain their family connections while the kids can stay in school,” Mirdoch says. “We look at this as another piece of the puzzle, because we are able to provide wrap around services to the family.”

The men will get weekly counselling sessions, therapy and a number of other supports. Rowan House Society has received $731,000 over four years through funding from Women and gender Equality Canada, a federal program.

In these next four years, the program will be assessed and data will be collected.

Prior to their launch, the organization developed a blueprint for how the program would work, with the hopes that this will be the new model for service delivery.

“How are the men learning to behave differently, what are they doing differently, and it seems like the victim is doing everything constructive where it should be the men,” says Mirdoch. “There really needs to be more services provided to the men. It’s just a shift of thinking. We need to do both, both are very important pieces of it.”

Experts and frontline workers say transformative programs are key to addressing gender-based violence, and intervention points where abusers can seek out help and support on their own are particularly important.

“In multiple places in Canada, the only way that men can get access to service provides who have expertise in this area, is by being arrested,” Scott said. “We want to be able to provide that kind of service before men are arrested.”